25 years of skepticism clings to nuclear plants

3/28/2004

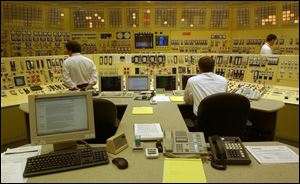

Reactor operators monitor and adjust operations in the Davis-Besse plant control room.

Twenty-five years ago today, America lost some of its naivete about nuclear power.

While historians view the 1960s as an era in which the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement, and the quest for sexual equality eroded much of the blind faith people had in public officials, experts believe a similar level of distrust arose with the nuclear industry after a five-day series of events began on March 28, 1979, at the Three Mile Island nuclear power complex about 10 miles southeast of Harrisburg, Pa.

Nuclear power had, until then, been largely embraced by the mainstream public as a technologically advanced form of producing energy that would help the U.S. remove the shackles of the OPEC oil embargo. Americans were eager for the day the nuclear industry would live up to its claim it could deliver electricity “too cheap to meter.”

Half or more of today's population was old enough in the late 1970s to remember the famous “Atoms for Peace” speech that President Dwight Eisenhower delivered on Dec. 8, 1953, signaling the dawn of the nuclear age.

But while America was figuratively and literally asleep at 4 a.m. on March 28, 1979, a meltdown was in progress at a TMI reactor that was a mere 90 days old.

The nation gasped. It held its breath. It prayed that some unthinkable radioactive explosion would be averted. Despite assurances that Harrisburg-area residents were safe, a nationally broadcast TV documentary years later reported it had obtained State Department records showing government officials had grave concerns about former President Jimmy Carter visiting the site.

Even today, the words Three Mile Island send chills up the spines of nearby residents and nuclear industry officials. Although no single death has been linked conclusively to the meltdown of TMI-2's reactor core, the debate rages on about how much radiation was released into the atmosphere and how many lives have been cut short by cancer.

“The question isn't if TMI caused cancer, but how much,” contends Eric Epstein, chairman of a watchdog group called Three Mile Island Alert.

Even the president and chief operating officer of one of America's largest utilities said there “is no question that TMI-2 was a major disaster” in terms of maintaining public confidence in nuclear power.

“It was a turning point. We must never forget it,” said Oliver Kingsley, Jr., of Chicago-based Exelon Corp., which now owns TMI-2's sister unit, TMI-1. That unit went online in September, 1974, and continues to operate today.

TMI-2, the younger of the two units, was the one that had the meltdown. It went online in December, 1978, and has remained closed since the accident. Akron-based FirstEnergy Corp., which owns Davis-Besse, inherited the unit as a result of a 2001 utility merger.

Ironically, the near rupture of the reactor lid at the Davis-Besse plant before it was discovered in March, 2002, is considered the worst safety failure in U.S. nuclear plant history, behind only TMI.

Skepticism abounds to this day as to how much information about the TMI meltdown was withheld from the public by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and Metropolitan Edison, the utility which had operated both Three Mile Island reactors in 1979.

NRC Chairman Nils Diaz is among those who believe there was a smug attitude — some senior-level NRC officials have gone so far as to call it an arrogance — about nuclear power then. “Indeed, few experts thought such an accident could ever happen,” he said.

Confidence in the technology was so high in 1979 that the whole concept of planning for an evacuation was an afterthought. Indeed, one of the legacies of the TMI crisis was that it led to the modern era of emergency evacuation planning at and around the nation's 103 nuclear plants.

On the third day of the crisis, President Carter dispatched Harold Denton, the NRC's nuclear reactor regulation director, to the scene to report back directly to him. Both had been trained in the nuclear Navy. The situation had grown so tense that Mr. Denton, who stayed three weeks, wore bullet-proof vests to the multiple press briefings he held.

“If you asked me a couple of years ago, I would have said the demons of Three Mile Island had been exorcised. But you can't quite say that today because of Davis-Besse,” Mr. Denton said at a recent nuclear industry conference in Washington. He ranked the near-rupture of Davis-Besse's reactor head in 2002, and the plant's temporary loss of coolant water in 1985, as the second and third most significant events, respectively, in U.S. nuclear history behind Three Mile Island.

The two events at Davis-Besse resulted in shutdowns in excess of two years and 18 months, respectively. But Davis-Besse is not an anomaly in terms of extensive, safety-related shutdowns: NRC records show there have been more than 25 of them since 1979.

Few parallels exist between the technological problems that occurred at TMI-2 in 1979 and at Davis-Besse in 1985 and 2002, even though the two plants have similar designs and were made by the same company, Babcock & Wilcox. Nuclear reactors designed by Babcock & Wilcox operate under higher temperatures and pressure than most others.

Mr. Epstein wonders if all the messages about Three Mile Island and Davis-Besse will get lost as memories fade. “To most young people, TMI, the Vietnam War, and civil rights are distant events — right up there with the pharaohs of Egypt,” he said.

“The big loser at TMI is democracy, because people feel impotent about the process,” he added. “The arrogance that existed at TMI was at Davis-Besse two years ago.”

Nevertheless, he said northwest Ohio was lucky because the Susquehanna River valley around Harrisburg “was held under a form of psychological terror” back in 1979. “It's a nightmare we haven't woken up from yet. There has been no closure,” he said.

Three Mile Island's legacy includes:

Contact Tom Henry at: thenry@theblade.com or 419-724-6079.