Bush's proposed cuts put spotlight on farm subsidies * New chart *

2/20/2005

John Tuckerman, who farms 1,100 acres near Blissfield, Mich., received $344,261 in farm subsidies from 1995-2003. He says the money sustains rural America and assures a safe food supply.

John Tuckerman, who farms 1,100 acres near Blissfield, Mich., received $344,261 in farm subsidies from 1995-2003. He says the money sustains rural America and assures a safe food supply.

Every year John Tuckerman plants acre after acre of crops - hay, soybeans, or wheat - hoping for warmth from the sun and just the right amount of rainfall.

It's an annual gamble for the Lenawee County farmer that has historically been worth the risk. One of the reasons: federal farm subsidies that pay Mr. Tuckerman and other farmers for planting certain crops and, in some cases, provide disaster assistance when crops fail.

Mr. Tuckerman received $344,261 in federal subsidy payments from 1995 to 2003, according to a database of U.S. Department of Agriculture subsidy payouts compiled by the Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit research group that advocates subsidy reform.

Although area farmers such as Mr. Tuckerman say subsidies are integral to doing business in agriculture today, the payments are again the target of critics and a presidential administration looking to reduce a massive federal budget deficit.

"When you plant a crop, you don't know if you're going to make a profit or not," said Mr. Tuckerman, 48, who farms 1,100 ares in the Blissfield area. "And if I don't make money, I have a hard time servicing my debt. I don't buy consumer goods. I don't buy as much fertilizer or equipment from our local businesses."

President Bush recently presented a budget that would chop the farm subsidy program by $5.7 billion over the next decade, including a 5 percent reduction in crop and dairy payments and an annual cap on the payments to individual farmers of $250,000. To date, farmers could be paid as much as $1 million in some cases.

The President's plan appeals to critics of the subsidy program, such as the Heritage Foundation, a nonprofit, conservative think tank that has long claimed the payments are "America's largest corporate welfare program," providing money to mostly crop-producing conglomerates that are slowly killing the smaller family farmer. In some cases, farmers are paid subsidies not to farm as part of the conservation program.

But records show only three farms in Ohio have received more than President Bush's proposed new cap of $250,000.

For Les Haas, 51, who cultivates 2,000 acres in Fulton County, subsidies helped keep him afloat when his tomato crop failed and when he was forced to buy a $190,000 tractor.

Although tomatoes are Mr. Haas' largest crop, his fields of corn, soybeans, and wheat placed him among Fulton County's top subsidy recipients. Haas Farms received $746,281 from the Department of Agriculture from 1995-2003.

"The other day I received our fertilizer bill. Now we have to buy fertilizer in the beginning of the season. I owe $80,000 for just part of our nitrogen bill. And the bill for my corn seed is about $40,000," said Mr. Haas, who has lived on his Delta farm all his life. "What we get from the government is peanuts compared to what my bills are."

Subsidies keep grocery costs low, a farmer notes

From 1995-2003, taxpayers spent more than $131 billion on federal farm subsidy programs, according to the Environmental Working Group's database. Farmers in Wood County received more than $106 million in farm subsidies during that period, making it second in Ohio only to the more than $107.7 million paid out in Darke County. Lucas County farmers ranked 54th among the state's 88 counties with $22.6 million.

In southeast Michigan, Lenawee County farmers received $116.6 million in subsidies, making it tops in the region and third largest in the state.

Farmers in Texas received the most subsidies from 1995-2003, followed by Iowa. Ohio was 14th in the country and Michigan 22nd in terms of federal subsidies given to farmers, according to the database.

And lifelong farmers such as Mr. Tuckerman say money from the government is a way to ensure a safe food supply for all Americans at an affordable cost.

"It's to provide a floor where, hopefully, food production won't drop to," Mr. Tuckerman said. "It's to give the consumer cheap food and to bolster the rural economy."

Dana Brooks, director of congressional relations for the American Farm Bureau, pointed out that it's not only the farmer who relies on the strength of the farming industry.

Each of the nation's more than 500,000 full-time farmers and ranchers produces food and fiber for 144 people, and more than 17 percent of the American work force produces, processes, and sells food and fiber, Ms. Brooks said.

Without subsidies, farmers hit by reduced crop profits would spend less money on farm equipment and supplies and on personal spending, and pay less in taxes, creating a ripple effect on local and county budgets and economies.

The proposed subsidy cuts come at a time when Ohio farmers set record harvest levels. The state's 2004 average corn yield is estimated at 158 bushels per acre, two bushels above the previous record set in 2003. Ohio farmers harvested an average 44 bushels of soybeans per acre from the 4.42 million acres planted - three bushels above the previous record set in 1998.

The Heritage Foundation questions why taxpayers are subsidizing farming at all, saying that the average farmer earns income 17 percent higher than the national average.

According to the Census Bureau, the average annual salary of farmers and ranchers is between $31,000 and $43,000. However, these figures can vary depending on a wide variety of factors, including the size of the farm and a particular year's yield.

But Brian Riedl, a federal budget analyst at the Heritage Foundation, pointed out that the subsidy program is "not based on how poor you are. It's not based on how bad your crops are. If subsidies are really meant to help the poor farmer, then why aren't they for all crops?"

That's a sentiment not lost on Jeff MacQueen, vice president of MacQueen's Orchard in Springfield Township. His family's 200-acre orchard receives little government help, even when disaster strikes.

"It's just a shame that the fruit industry isn't as big as the grain [industry], because the fruit industry does need help," he said. "For us it's tough luck, lick your wounds, and start over."

Mr. Riedl of the Heritage Foundation said the big problem with farming is the variability of weather. "So the answer is to have a system based on insurance," he said. "Subsidized crop insurance would cost only a couple of billion dollars a year rather than [more expensive] permanent subsidies."

In a 2001 analysis of farm subsidies, Mr. Riedl pointed out that among those farms receiving the highest dollar amount are companies "that clearly do not need them," including John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance, which received about $42,000 a year, and Caterpillar, which received about $34,000 a year.

Mr. Riedl also said that while the average farmer received about $900 a year, wealthy landowners like David Rockefeller, the former chairman of Chase Manhattan and grandson of oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller, received an average of about $70,000 a year. Retired NBA basketball player Scottie Pippen receives $26,315 annually not to farm land he owns in Arkansas.

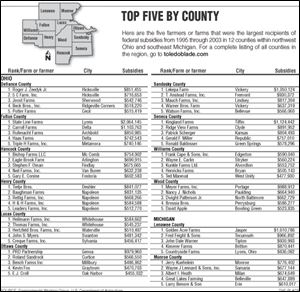

While critics focus on the 10 percent of the nation's farmers they claim receive about 60 percent of all federal payments, payment records reviewed by The Blade show the average farmer in northwest Ohio and southeast Michigan is not on this list. Those in the area that are listed as the top subsidy recipients are farms run by generations of the same family - not corporations.

Dick Gallup, who owns State Line Farms in Lyons, Ohio, reminded critics that subsidies mean farmers won't have to hike prices on products to make up for losses. He called it an assurance program that allows Americans to continue buying a loaf of bread for about $1.

"People work less hours to pay for their food here than anywhere in the world," Mr. Gallup said. "That's what these payments are for."

State Line Farms, with farmland in Fulton County and across the Michigan border in Lenawee County, received more than $2 million in subsidies from 1995-2003.

Mr. Gallup's farm is only one of three in this region that would have been affected in years past had a cap on subsidies been set at $250,000 as the President has suggested. In 1999, 2000, and 2001, State Line Farms, the KRG Partnership in Upper Sandusky, Ohio, and Golden Acre Farms in Lenawee County topped the proposed cap.

Mr. Gallup said he knows that some remain skeptical of the program, but he notes that it helps farmers compete against foreign agricultural imports. And by limiting imports, he said, Americans are ensuring a safer food supply and preserving jobs. Mr. Gallup said he employs anywhere from seven to 30 employees, depending on the season.

Cotton and rice growers tend to receive the largest share of federal subsidies, followed by corn, soybeans, and wheat. As a result, the budget proposal puts President Bush at odds with farmers in his native Texas and other southern states, where rice and cotton are key crops.

Carl Zulauf, an agriculture economist at Ohio State University, cautioned farmers to remember that, at this point, the President's proposed budget is just a recommendation that must be approved by members of Congress concerned about the impact in their states. But he acknowledged that the nature of the proposed cuts will likely mean that all farmers will feel the effects of any cuts. How much, he said, will depend on how they are applied and the individual farmer's current financial situation.

"[For] those in financial difficulty or on the cusp of financial difficulty, this budget could potentially put them out of business," he said.

Contact Erica Blake at: eblake@theblade.com or 419-724-6076.