An annual bull market

7/3/2005

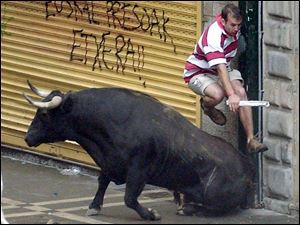

A bull makes a turn around a corner as runners scramble to get out of the way during Pamplona's Running of the Bulls.

FRANCOIS MORI / Associated Press

The weeklong festival in Pamplona, Spain, features daily runs with the bulls, which often entail close encounters with injury.

PAMPLONA, Spain Arriving in Pamplona during the famous Fiesta de San Fermin is like waking up in a zombie movie.

Everyone in the hazy, early-morning light moves slowly, steadily, silently in the same direction. And all of them, each and every one, are dressed identically.

The buses, all traveling the same way, are filled with riders wearing white pants and shirts, red sashes and scarves the colors of this proud Spanish region. Likewise, the sidewalks are a candy-cane stream that flows only one way.

It s eerie. Incredibly eerie.

And yet it seems only appropriate. Everyone in town is under the same spell, here for the same reason: the Running of the Bulls.

This long-standing yearly tradition, dating back to the 14th century, in which thousands of people race the streets alongside 1,000-pound beasts takes place every morning from July 7 to July 14. It is one part mystical, one part practical.

Its purpose is simple enough transporting the bulls from the corral on the edge of town to the bullring where the evening s bullfights will occur. But for generations, it has also been a test of courage for those who dare.

Before the running begins, however, there is a certain amount of business to conduct. So on July 6, hundreds of thousands of people flood this town, ballooning it to three times its size. They come to officially open the weeklong Fiesta de San Fermin, a fourth-century Christian who was tortured and beheaded for his faith and who became patron saint of bakers and wine merchants.

The air is full of merriment and song and the streets flow red with wine that revelers spray at each other as often as they drink it. Locals stand watch from their balconies, sometimes safely behind sheets of clear plastic to ward off the liquid spirits of those below.

Everyone marches toward the main square, though there is not nearly enough room for all. Cheers rise in anticipation until at noon, the mayor of Pamplona ascends to the balcony of the Town Hall to shoot off a rocket signaling the opening of the fiestas.

The moment is followed by a roar that could just as well be the Earth cracking open in its excitement. Instead, it s just the crowd, doused in streamers and confetti that come from nowhere and nearly block the sun as visitors from all over the world continue to cheer and wave flags and red scarves in the air.

Taking its cue, the band begins to play the city has its own Town Hall brass band, La Pamplonesa, for the festival and those who follow its tune march over to the square of the Navarreria. There, rowdy foreigners take turns climbing up and jumping off the fountain into the (hopefully) waiting arms of their friends.

The celebrations and drinking continue well into the night, so much so that many visitors, unable or unwilling to find a place to stay in Pamplona, simply sleep along the streets and in the parks.

A bull makes a turn around a corner as runners scramble to get out of the way during Pamplona's Running of the Bulls.

No matter; everything is mostly forgotten by morning. The locals come out before dawn and hose down the ancient, narrow roadways and any evidence of the excesses of the night before.

Somewhere far off, the band plays a whimsical tune, a wake-up call for the many still dreaming on the cobblestones, calling them to attention as everyone prepares for the Running of the Bulls.

The run itself is not that long less than 900 yards through the winding labyrinth of the city s old quarter. There are no requirements for runners other than that they be 18 years old. The overwhelming majority are male.

Despite what your gut may tell you, history says the overall odds of not surviving the race are slim. More than a dozen people have been killed by bulls in Pamplona since 1924.

Still, there are some tips to further improve your chances. Some are obvious: Don t party too hard the night before and don t take bags or other foreign objects with you.

(Seriously. Two years ago, a friend and I were in the middle of the street, just minutes from the start of the run, when a policeman noticed our cameras and told us to leave the course. We found ourselves having to settle for watching the action through slats in a fence.)

Other tips are the results of years of trial and error by less-fortunate runners: Stick to the inside at turns in the route, where the bulls often lose their footing on the slick cobblestones and crash into the opposite wall.

Take a rolled-up newspaper and use it to help guide the bulls safely past you. (Bulls are faster than humans, so don t even think about outrunning them.)

If you fall down, stay down. The prevailing wisdom is that it s better to be stepped on and crushed by an angry, grunting monster than to stand up and risk getting gored.

A tall, thick wooden fence lines the route keeping the bulls on course, but also penning the runners inside once the race begins. Don t plan on jumping the fence, since it is high and topped by eager spectators.

As the time nears, most runners mill about nervously bouncing, pacing, talking softly. Others, a few old-timers, sit calmly, backs leaning against the wall, gazing at the balconies full of spectators lining the street a narrow, crowded road with hardly any crevasses or doorways or hollows offering protection.

The run begins at 8 a.m., when a shrieking rocket signals that the corral had been opened. According to one travelogue, the appropriate action for runners is to begin jogging. In practice, it means run like crazy (or in the case of some runners, dive to the ground and try to squeeze under the wooden fence).

The sound of a second rocket means the bulls have left the corral and started running. According to tradition, this is a signal to those in the street to start sprinting, something most have been doing since the very beginning.

This is about the time that things feel like a zombie movie again. Everyone s running in a collective panic, but you cease hearing the runners as they pass and the crowd s roar seems mute. All is quiet. Then, out of this slow-motion silence, comes the clanging of cow bells tra-lang! tra-lang! tra-lang!

And then whoosh! the bulls rush by and it s over.

Left in the road is the detritus of runners with scrapes and bruises and even a little blood. But things aren t really over. Not yet.

It s not enough for visitors to run alongside a half dozen bulls; they must confront them face to face. Runners who make it in time (and anyone who chooses to hop over a small wall) actually join the bulls in the bullring.

The animals are rounded up and then smaller bulls are released into the waiting crowd sealed in the bullring a chance for the beasts to exact a little payback before things get deadly serious later that night.

To the strange delight of everyone, the bulls (horns safely blunted) rush through time and again, smashing a path through the crowd.

Often the wall of humanity parts just in time, but just as often the bull hits its mark and butts into anyone with a slow step.

No harm done the crowd simply rushes in to distract the bull and save one of its own.

There s no place for fear here. Runners antagonize the beast, screaming and waving their arms, tiptoeing closer and closer, daring it to charge them. And when it does, they begin a mad dash for somewhere, anywhere else.

Sometimes, just to stir things up, a second bull is sent rampaging into the crowd but only after the group s attention is focused on the first one.

It s not really fair, but everyone s OK with that, too. They know that things will be different at night, when the arena is filled to bursting with fans clad in red and white and carrying skins full of wine.

None of the magnificent beasts will escape the matador s artful death stroke then.

But for a few, brief moments, there s no thought of that. The beasts are running the show.

Contact Ryan E. Smith at: ryansmith@theblade.com or 419-724-6103.