Mother pushes for childproof packaging

8/2/2005

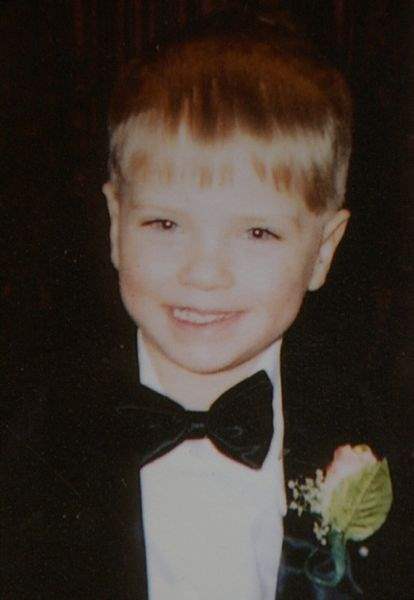

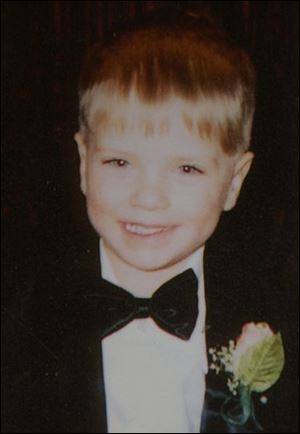

Timmy Rhodes

king / blade

Stephanie Rhodes during a court appearance.

An East Toledo woman convicted in her son's death from a pain medication overdose is trying to ensure that other children don't die the same way.

Stephanie Rhodes is appealing to two government organizations and one nonprofit group in an effort to require pharmaceutical companies to enclose medicated patches in child-proof containers. Mrs. Rhodes' 4-year-old son, Timmy, was found dead in January after he stuck a fentanyl patch to his leg.

Last week, Mrs. Rhodes was sentenced to five years' community control for leaving a fentanyl patch in a place where Timmy could access it. The 28-year-old woman had a prescription for fentanyl, a pain medication about 80 times the strength of morphine, to help her deal with the effects of Crohn's Disease, a debilitating intestinal disorder.

"Once my son was able to get a hold of one of these patches and we saw how easy it was, we wanted to make a change," Mrs. Rhodes said. "These aren't safe, and there's got to be a different way."

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration requires any prescription medication in pill form to be enclosed in child-proof bottles, but there is no similar restriction for medicated patches. Duragesic, the most common brand of fentanyl patch, comes in foil pouches inside cardboard boxes.

"It's easier to open than a packet of mustard that you get from a drive-through," said Rhonda Tomase, Mrs. Rhodes' aunt and the person coordinating the family's efforts for legislation.

Timmy Rhodes

Last week, Mrs. Rhodes and Mrs. Tomase began contacting government groups and medication watchdog organizations to investigate how to prevent other children's deaths. They have filed adverse incident reports with the FDA, the Consumer Product Safety Commission, and the private Institute for Safe Medication Practices.

Michael Cohen, president of the institute, said he became interested in Mrs. Rhodes' cause because Timmy's death highlighted a problem that most medical professionals had never fully taken into account. Neither he nor a spokesman for Ortho-McNeil, the company that manufactures Duragesic, had heard of any other case in which a child died from a fentanyl overdose.

Two weeks ago, the FDA issued a warning about the effects of fentanyl, which has been linked to 120 deaths nationwide since it was first approved in 1990. Revised patient information sheets now carry expanded information about potential side effects of the drug, which include trouble breathing and dizziness, but the advisory did not address the effects of fentanyl on children.

Pharmacist Norman Folkman holds a pain patch, similar to the one that killed Toledo boy Timmy Rhodes.

Mr. Cohen said medications approved by the FDA today would be held to a higher standard than fentanyl was 25 years ago. Many newer medications, especially those that involve needles, come with biohazard boxes for discarding them, he said.

"They didn't anticipate some of the problems we've seen," he said. "If someone had come up with the Duragesic patch today, we'd know to anticipate problems like accessibility to children."

Mrs. Rhodes, who stopped taking fentanyl after her son's death, said she will push for biohazard boxes to be included with medicated patches. Those containers cannot be opened and have a small slit at the top to discard used patches.

If her Duragesic prescription had come with biohazard boxes, Mrs. Rhodes said, Timmy might still be alive today. The instructions included with fentanyl patches say that users should flush them down the toilet after use.

That didn't work for Mrs. Rhodes, who said she clogged her toilet three times from trying to follow those instructions. Instead, she generally put the patches inside soda cans, but when she did not have a can available she put the used patch directly into the garbage can, she said.

"When you have a child who is hyper and climbs everything it's hard to keep these things completely out of reach," she said.

Doug Arbesfeld, a spokesman for Ortho-McNeil, which sold more than $2 billion worth of Duragesic in 2004, said his company was willing to listen to Mrs. Rhodes' suggestions.

"We're always watching reports that come in, and based on what we learn from how a product is used we make decisions about changing things," Mr. Arbesfeld said. "It'll be interesting to hear what comes out of this."

Contact Megan Greenwell at:

mgreenwell@theblade.com

or 419-724-6050.