Immigration limits invite violations, local experts say

12/4/2005

First of two parts

After years of getting by on poor harvest seasons and meager resources, Nabor Campos knew that he could not stake his family's well-being on the unpredictable soil around Nuevo Leon in northeastern Mexico.

So, 17 years ago, Mr. Campos - like countless countrymen before him - journeyed north to the United States in search of "any means to provide for my family." Unlike thousands of illegal immigrants who cross U.S. borders every year, Mr. Campos and his family are here legally.

"It was not easy, but I was looking for a better life for my wife and my children," said Mr. Campos.

These days he and his wife put in long hours at the Consolidated Biscuit Co. cookie factory in McComb, Ohio.

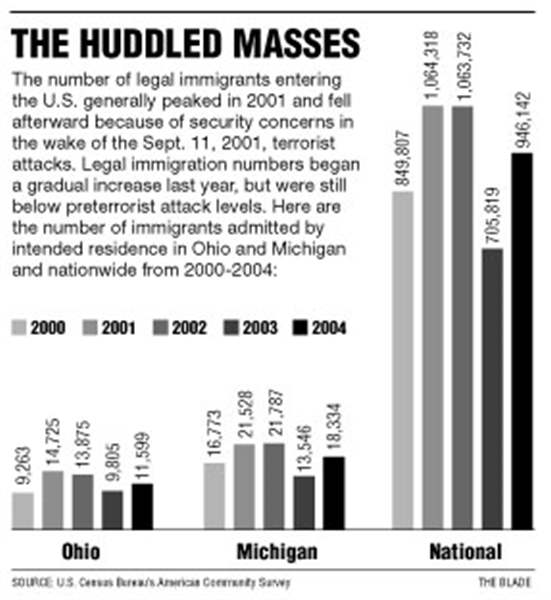

The couple is among more than a million immigrants from all corners of the world who enter the United States every year.

On Monday, President Bush announced an immigration-reform proposal that would tighten border security and establish a temporary guest worker program. It also would reject complete amnesty for illegal immigrants already in the country.

Mr. Bush hopes his plan will resolve disagreements within his Republican Party on what to do about this key domestic issue as well as win bipartisan support that would include Hispanics - the nation's fastest-growing minority.

Mr. Campos and his family, who reside in Fostoria, and other Hispanics are among those most affected by America's immigration policies.

But many immigration experts and legal immigrants contend that the nation's immigration policy and the complex process immigrants face are what foster illegal immigration.

For immigrants like Mr. Campos, 54, who regularly deal with the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, the system is often slow, indifferent, and expensive to maneuver.

"It depends on the immigration system and God," Mr. Campos said.

"Many people in Mexico want to come here legally, but they cannot because it is very difficult. So they have to come in other ways," he said.

After more than 10 years of working as a landscaper and farm laborer, Mr. Campos successfully applied for one of the very competitive temporary work visas for his wife, Guillerina, 47, and three of their children to legally enter the United States from Mexico last year.

The Campos family now squeezes into a two-bedroom mobile home just off of Main Street in Fostoria.

A changing trend in settlement patterns in recent years has produced "new growth" states where the number of migrants and legal immigrants has jumped in states such as Ohio, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Iowa, and North Carolina.

The immigration debate has been a polarizing issue in certain regions of the country, particularly in border states in the southwest, Florida, and states such as New York and Illinois that receive most of the traditional flow of immigrants.

President Bush last week traveled to two of the border states - Arizona and Texas - to announce his immigration reform campaign and acknowledged the battle ahead.

"Illegal immigration is a serious challenge," Mr. Bush said. "And our responsibility is clear: We are going to protect the border."

Mr. Bush said his reforms are designed to crack down on those who enter the country illegally while offering more green cards and temporary visas to workers who want to earn a living - often performing jobs many Americans don't want to do.

"The American people shouldn't have to choose between a welcoming society and a lawful society," he said. "We can have both at the same time."

That claim will be a tough sell. A representative of the Toledo-based Farm Labor Organizing Committee contends Mr. Bush's reform proposal "blatantly discriminates" against today's new immigrants, who are mostly Latinos. The temporary guest worker program would create "quasislaves" who ultimately will be sent home "after they have left their sweat and blood here," wrote Beatriz Maya, FLOC's co-director of organizing, in response to Mr. Bush's proposal.

America is "a nation built by immigrants" from Germany, Ireland, Italy, and other countries, Ms. Maya wrote..

"Throughout U.S. history, new immigrants were brought to do all the back-breaking, poorly paid, risky jobs that residents did not want," she said.

"There is nothing different about the immigrants who came to America before and immigrants now ... The difference today is in the color of the skin," she stated.

Even within his own party, Mr. Bush faces difficult footing.

In Arizona, for example, Republican Sens. John McCain and Jon Kyl are on opposite sides of the issue. Mr. McCain favors legislation that would allow those in Mr. Bush's temporary worker program the chance to someday become citizens. Mr. Kyl opposes that policy.

In the immigrant communities, where pro and anti-immigration activists will make their cases, legal immigrants say the debate should focus on the broader question of how U.S. immigration rules affect how people come to and stay in America.

Noah Pickus, a professor of ethics and public policy at Duke University, contends that the upcoming congressional debate is promising but incomplete because it lacks the will for real immigration reform.

"Our attitude toward immigrants says we won't invest much and we won't expect much," said Mr. Pickus, associate director of the Kenan Institute for Ethics at Duke. "We have developed a laissez-faire approach in our immigration policies. There is no middle ground and there is a wide disconnect between politicians and the actual realities of immigration."

This disconnect is strengthened by myths and misconceptions about the causes and patterns of immigration, said Sister Mary Jo Toll, director of migrant and immigrant outreach at the Secretariat for Pastoral Leadership in the Catholic Diocese of Toledo.

She is also the coordinator of En Camino, a nonprofit collaborative between the Toledo Catholic Diocese, Sisters of Notre Dame, and AmeriCorps of Northwest Ohio, which helps migrant farm workers and immigrants in rural northwest Ohio through the U.S. immigration system.

Seated in her office at En Camino, housed in a five-room walk-up on Perry Street in Fostoria, Sister Mary Jo said a growing number of seasonal migrant workers in northwest Ohio have moved from farm work to other jobs in the last 10 years.

"They now want to stay. They work in factories, restaurants, slaughter houses, and in the agriculture industry," she said.

"Many of them are even recruited by employers in the area," she said.

Most of the migrants who settle in northwest Ohio are responding to a struggling agricultural industry in the state, said Bert Gonzales, a coordinator at Rural Opportunities Inc.

The nonprofit employment and training agency in Fremont receives federal funds to help migrant seasonal workers make the transition from field work to permanent residency and jobs in manufacturing.

"When I started out in the field, we had a variety of fruits and vegetables to harvest," Mr. Gonzales, 45, said. "But now there are mostly just pickles and tomatoes."

He said migrants who make the transition from the fields must have skills that can get them placed in other jobs in order to survive.

"Many of these workers travel from states across the country, and you never know what Mother Nature is going to bring. If we have bad weather and a poor season, how can you feed your family?" said Mr. Gonzales, a Texas native who grew up in a family with generations of seasonal workers.

Instead of simply passing through, Mr. Gonzales said, most migrant seasonal workers now stay and try to change their visa status or work permits to take more permanent jobs.

"On average, we 'settle out' 37 families in this region every year," he said.

At En Camino, Sister Mary Jo and her staff deal with husbands, wives, and children from Mexico, Guatemala, and other parts of Latin America who come to learn English, get help with filling out immigration forms, applying for work permits and Social Security cards, or even opening and maintaining bank accounts.

"The immigration system is incredibly backlogged," said Sister Mary Jo, who is fluent in Spanish and teaches daily English-as-a-second-language classes. She contends that a limited number of work and family visas for the people who want to legally enter the United States is one of the major causes of the high numbers of illegal immigrants.

There are 66,000 temporary H-2B visas in 2005 that are specifically designated for seasonal migrants. Competition for these visas is stiff, however, and people who don't qualify in this visa category are most likely going to end up in the country illegally, she said.

For many, the H-2B visa, created specifically for seasonal migrant workers in the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1996, is very hard to get because of its limitations on workers and employers. Potential employers must be able to prove to their state work force agencies and the U.S. Department of Labor that extensive efforts have been made to hire American workers for jobs that are often filled by seasonal low-wage laborers.

Large-scale farms that depend on low-wage workers and some area companies use an unconventional recruiting network that immigration experts indicated can often entail immigrants paying fixers to recruit them and transport them to work sites across the country.

Because of its competitiveness, the experts said, the H-2B visa quota is always filled within the first three months of each fiscal year. That forces those without visas to make choices.

"If you can't come in through the front door, you come in through the back," said Sister Mary Jo, noting that there are more than 11 million undocumented workers in the United States.

Mr. Campos said he played by the rules when he came to America, but the cost was tremendous. He waited for more than 10 years and paid thousands of dollars in processing fees over time through legal and illegal channels before his wife, two sons, and a daughter were granted temporary work visas allowing them to enter the United States.

During the long application process, his oldest daughter, Sandra, "aged-out" of the process because she was over 21 when her immigration paperwork was finally processed and she could not qualify for a work visa. She remains a factory worker in Mexico making less than $50 a week, Mr. Campos said.

In a process where deadlines are critical, the immigration system itself can make the difference between being a legal resident and an illegal alien, experts said. Many people who enter the country legally often become "out-of-status" illegal residents because of the time it takes for their cases to be heard or an application to go through different stages.

In Ohio, the Justice Department recently announced steps to reduce the backlog of immigration cases in the state by opening an immigration court next year. Ohio Republican Sens. Mike DeWine and George Voinovich lobbied for creation of an immigration court in Ohio to reduce the state's 2,999-case backlog - one of the largest in the 27 states that do not have their own immigration courts.

On a quiet fall Friday night, Mr. Campos sat surrounded by his family in a small living room decorated with pictures of the Virgin Mary and furnished with a couple of couches, a television, a washer and dryer, and a dining table. He worried that his children - Norma, 23, Francisco, 17, and Efren, 11 - still face an uncertain future.

They do not speak English, have barely acclimated themselves with the education system here, and live in a mobile home community sequestered from life in most of Fostoria.

The language, as well as social and economic differences between immigrants who perform farm and manual labor and the people in the communities in which the immigrants live, are among the reasons that immigration remains a polarizing issue, said Duke University's Mr. Pickus, author of a recently published book, True Faith and Allegiance: Immigration and Civic Nationalism.

"Because there have traditionally been no mechanisms to allow for immigrant intake, a lot of Americans feel insulated from immigration and immigration policy," Mr. Pickus said.

"There is a questioning of the social order when a particular immigrant group hits a critical mass in a small community and people are branded as racists when they react negatively to the newcomers," he said.

Although language is generally less of a problem in border states like Texas, it is often the initial fault line of controversy in immigrant growth states like Ohio. State Rep. Courtney Combs (R., Fairfield) has proposed introducing a bill in the General Assembly next year that would mandate English as the official state language.

"I have heard from law enforcement, school, and hospital officials who complain of language problems," said Mr. Combs, whose district is in southwest Ohio's Butler County - a region booming with migrant workers spurred by a growing construction industry.

Among other things, his proposed "Ohio English Unity Act" would not require state agencies to translate official documents into other languages.

The proposal has been branded as "intolerant" and "divisive" by the Ohio Commission on Hispanic and Latino Affairs, which has indicated it will fight such legislation.

Mr. Pickus said the key shortfall with America's immigration policy is that most politicians and the reforms they propose do not consider the integration of newcomers into American society - particularly the issue of language.

While states cannot control the flow of immigration, Mr. Pickus said they need to make changes in their rules and procedures for receiving immigrants as residents.

Sister Mary Jo agrees.

As a social worker on the immigration frontline, she said many immigrants are not prepared to face the language, transportation, health care, education, and other cultural issues of living in northwest Ohio communities.

"It is a hard transition for many families to make," she said.

Contact Karamagi Rujumba at: krujumba@theblade.com or 419-724-6064.

TOMORROW: Current U.S. immigration rules on visa for skilled and educated workers don't encourage citizenship and risk losing knowledge and technology to other countries.