Scars relate stories of teenage torment

3/12/2006

Ruthanna Clinger hasn't cut herself in months. It's a 'really hard thing not to do,' she says.

Ruthanna Clinger hasn't cut herself in months. It's a 'really hard thing not to do,' she says.

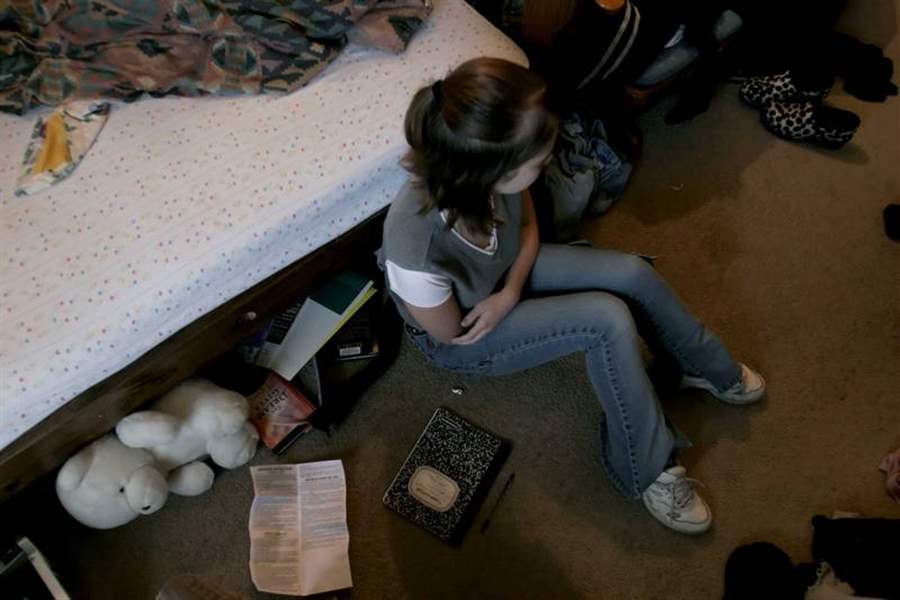

Ruthanna Clinger's bedroom is full of things that have made her happy: pictures of horses, inspirational quotes, some stuffed animals.

And one razor blade.

Hidden on top of a bookcase next to her bed, it doesn't make her happy anymore. But on innumerable days darker than any 16-year-old should know, it once did.

On those occasions when she would cut herself - little surgical slices along her wrist or arm - the happiness was red and dripping and all too brief.

"It didn't feel like any cut or scrape I had before," said Ruthanna, who lives in Upper Sandusky. "It felt really good, relaxing, and just the sensation of the pain and the blood for a minute kind of made me happy."

Only for a minute. The more she did it, the deeper she had to cut and the shorter time the feeling lasted, unable to adequately cover up the pain of family troubles and the stress she felt of being forced to grow up too fast.

Ruthanna isn't alone. She's part of a population that is growing, especially among adolescent girls.

Just how many cutters are out there is hard to say, but experts suggest that at least 1 percent of the general population in the United States, including adults, has engaged in some form of self-injury, which could be anything from cutting to biting, burning, or hitting oneself.

Scars from self-inflicted wounds mark the lower arm of Ruthanna Clinger, who began cutting herself a few years ago but has since stopped. 'I want a lot more than cutting myself for the rest of my life,' she says.

Considering only adolescents, those numbers could be much higher. Studies cited in the February, 2005, issue of the Journal of Abnormal Psychology indicate that anywhere between 14 percent and 39 percent - a broad range, no doubt - could engage in self-mutilative behavior.

Dr. WunJung Kim, a child and adolescent psychiatrist and professor emeritus at the Medical University of Ohio, said two-thirds of them are girls, and he's seen some younger than 10. They are being identified earlier than ever, sometimes because specialists are more aware of the problem and sometimes because cutters seem to be more open about the practice.

It's out there for those who aren't afraid to see it. Celebrities like Angelina Jolie, Christina Ricci, and Courtney Love have admitted to self-injury, and there are numerous Web sites with titles like "Razor Blade Kisses" dedicated to telling personal stories about cutting, sharing pictures of scars, and offering words of encouragement to those who need help.

Jolene Siana, a pseudonym used by a Waite High School graduate, recently wrote the book Go Ask Ogre, detailing her adolescence as a cutter in the late 1980s. It's filled with letters she wrote to a rock star at the time, providing images of depression and pain.

"I found my razor blades. I cut my wrist just enough for it to bleed," she wrote. "I couldn't stop crying. I wanted to be able to dig the blade into my arm, but I kept crying. I wanted to die so badly. I wanted to bleed. I was clenching my wrist with my other hand and I could see the blood gushing between my fingers."

If you don't know about cutting, your kids probably do. At times, the practice has even become a kind of fad among schoolchildren.

"It's contagious, infectious. It has to do with the suggestibility of the kids," Dr. Kim explained.

One former self-injurer who recently graduated from Perrysburg High School said it's more common in the area than adults might like to think.

"I know at least 30 girls who did it," she said. "A lot of the girls at our school were actually cutting just to cut, just to be popular like that. I guess it's just they feel like they're not getting enough attention and that other people who are doing this are getting attention."

This woman, who requested that her name not be used, cut herself a few times but preferred using a lighter to burn her fingers.

Perrysburg High School Principal Michael Short said the girl's estimates don't shock him.

"I have not seen it here, although I'm certain it goes on because of the prevalence of it nationally," he said.

But why cut or burn at all? It may be hard for most people to conceive how someone could bear routinely rubbing against a razor's edge, let alone enjoy it.

"It's kind of a weird thing," Dr. Kim said. "It varies from one individual to another in terms of motivation."

For many people, the practice can be a sign of different conditions, anything from depression to bipolar disorders. There can be a correlation to physical or sexual abuse too.

Cutting for the first time tends to be an impulsive act, often as a way of coping with intense emotions. Some say they use a knife as a release valve to let out pain that builds up inside. They may seek the opposite as well, inflicting pain on themselves so that they feel something - anything - to combat an increasing numbness to the world.

"[For them,] it's a control issue. I can't control the pain that people are bringing into my life, but I can control this," said Mark Anderson, a licensed counselor at St. Charles Mercy Hospital in Oregon.

Some cutters even talk about it being addictive, suggesting the act of cutting generates internal opiates called endorphins, sort of like a "runner's high."

"The kids will talk about that incredible release and rush of doing it. It's really just [being] addicted to the feeling of letting that tension out," Mr. Anderson said.

That's exactly how Shirley Manson of the rock group Garbage described her experience during a 2000 interview with the Scottish newspaper The Herald.

"I wouldn't say that cutting was pleasurable, but there is a sense of euphoria that follows cutting yourself," she said. "The quick pinch of pain and the sight of blood snaps you back to the surface and you start to appreciate being alive."

Most people who cut start between the ages of 12 and 16, experts say. They are more likely to be girls because they internalize pain and anger instead of acting out.

"I think for teenage girls, there's a lot of change in that period of life - hormonal, social pressure, expectations of parents, family, getting good grades, society's pressure to act a certain way, look a certain way. You put that all together in adolescence and you really have a lot of people who have difficulty coping with that," said Jennifer Fabrizio, a clinical psychologist at Children's Safe Harbor, a collaboration between Harbor Behavioral Health Care and Toledo Children's Hospital.

Cutting seems to be less common among minority children, which some experts say could be because of a closer family structure and support network among those groups.

"It's mostly more affluent, white, middle-class kids," Mr. Anderson said. "It's typically kind of the quiet kid," he continued. "They're usually not your serious acting-out kids. It's the ones who are internalizing it."

When Brittany, a Bowling Green State University freshman who asked that her last name not be used, first cut herself, it was a reaction to events in her life that she saw spiraling out of control as she entered college. She'd read about cutting in Elizabeth Wurtzel's Prozac Nation and felt like she'd run out of options.

"I guess I got depressed when I got here," she said. "I didn't know anybody. I was having problems at home and problems with a certain guy I was seeing. I didn't have anybody here that I could talk to about it, so one day I just picked up a pair of scissors and I mostly just cut my forearms."

A few months later, she had 30 scars.

"It didn't hurt," she said. "Actually, it made me feel better. I guess it's just kind of a way to release your feelings without yelling."

Cutting doesn't have to be a call for attention, but that can be part of it. The first time Ruthanna cut herself a few years ago, it was at her family's dining room table with a kitchen knife while her family was home.

"I kind of wanted to see if anyone would notice," she said.

They didn't. It took more than two years before others saw beneath her cuff bracelets and makeup and her excuses of being scraped by a dog or getting in a fight that she used for cover. By then, there were horizontal scars most of the way up her arm, and she started cutting in less obvious places, like her stomach and legs.

It became a kind of ritual. She cut herself a few times a week, usually in her bedroom or bathroom with clothes or bandages nearby to sop up the copious amounts of blood. Sometimes she did it away from home when the urge became irresistible. On those occasions, she would use a sharp object she kept in her pocket or grab a knife from someone's kitchen.

It's not that she and other cutters are trying to kill themselves. That can be an issue for cutters - Ruthanna did have suicidal episodes and said she once swallowed a bottle of pills - but many who end up in the hospital only do so because they've accidentally cut too deep.

"The intent is: I don't want to end it, I just want to reduce it. I want to reduce the pain that I'm experiencing," said Mr. Anderson, the licensed counselor.

It's usually a hidden practice - cuts in places that aren't readily seen, wounds that won't heal hidden by long sleeves in the summertime.

That's why Dr. James Kettinger, a physician at BGSU's Student Health Services, suspects there are many more than the five to 10 students he sees with the problem each academic year. He brings it up especially when he's talking to students with mood disorders.

"I ask the question a lot these days," he said.

Treatment often includes counseling and coping strategies. Clean your room, listen to music, write things down, exercise - anything to deal with the internal pressure without resorting to razors. Identifying and treating the underlying condition at the root of the cutting are important too.

Karen Conterio and Wendy Lader, authors of the book Bodily Harm, have established a clinic in Illinois tailored to the problem. The program, S.A.F.E. (Self-Abuse Finally Ends) Alternatives, is a small one that works for 30 days with people who have a history of self-injury.

It provides a psychiatrist for medical management, requires writing exercises that ask cutters to outline alternatives to their behavior, and facilitates communication and family therapy.

"I tell parents not to understand it per se but to appreciate anyone who would go to that length of masking pain or managing pain. They're in a lot of pain," Ms. Conterio said.

The BGSU student said she decided to stop cutting when a friend said how much he worried for her.

"That's when I realized that I couldn't keep going on like this," she said. "It's college. I'm supposed to be having fun, not sitting in my room cutting myself."

Ruthanna never sought help until she was caught.

"I've started seeing about how my pain affects other people, how people I didn't know cared, actually cared," she said. "I want a lot more than cutting myself for the rest of my life."

She hasn't cut herself in months, but she was admitted into the Kobacker Center's inpatient program at the Medical University of Ohio once when she didn't think she could hold off much longer.

When she made those first cuts a few years ago, she never would have guessed it could come to this.

"I never really thought I would actually do it until it happened, and it shocked me that I did it," she said. "It became kind of something I enjoyed. Most people, they need a cigarette. I would need to cut myself."

Now she's discovered, too late, it's not the kind of urge that goes away easily.

"For a long time, I would just be in school and I'd sit there and I'd fantasize about how wonderful it would feel to just cut away and have the thrill of it again," she said. "It's actually a really hard thing not to do it."

Contact Ryan E. Smith at: ryansmith@theblade.com or 419-724-6103.