One year later, cocaine death of St. John's student is still a shock

7/7/2006

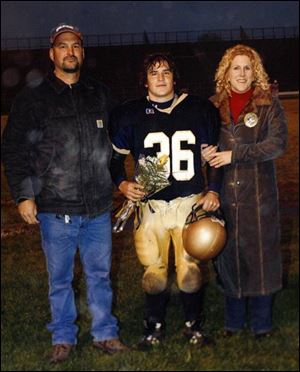

His coach had no inkling of Rusty s drug addiction. The youth is with his father, Rick Marvin, and mother, Amy Adams.

Shock. With the teen's death, everyone felt it.

Some knew Rusty Marvin, the ever-smiling, much-hailed St. John's Jesuit High School varsity football player, to be equally addicted to God and cocaine. They'd heard him tell of how the second helped him discover the first; how the first implored him to abandon the second.

But a year ago today, when the senior who school officials touted as a class leader and prayer group founder was found dead in his garage of a cocaine overdose, it struck them all like a thunderclap.

His mother, Amy Adams, remembered an intense discussion with her 18-year-old son months before, while he suffered through a whirlwind of chemical and spiritual craving.

"Why is it so hard for people to follow in God's footsteps?" she remembers Rusty's asking.

"I told him, 'It's easier to do it the other way.' "

His coach had no inkling of Rusty s drug addiction. The youth is with his father, Rick Marvin, and mother, Amy Adams.

To this day, a date remains etched in Ms. Adams' memory - July 7, 2005. "I told everybody at work, it's my day to be with him," she said.

Rusty had come into her room about midnight the night before. The two talked excitedly about the day to come, about his registering at the University of Toledo.

It was going to be one fine day, Rick Marvin also mused when he woke up that morning. Rusty's father, a real estate agent, motorcycle aficionado, and 25-year drug addict, was at the 60-day mark with his Alcoholics Anonymous group. He was set to receive his second coin, the one AA participants get each month they last.

There was energy in Mr. Marvin's step as he walked out of his Ottawa Hills home to the garage behind it to warm up his motorcycle for the ride to work.

But as he was opening the garage's side door, he remembered his bike was parked outside.

"I wondered why I even went in," he said.

Rusty Marvin was fascinated by his mother s necklace that contained a verse from the Gospel of Matthew.

Opening the door, distracted, he noticed Rusty collapsed against the main garage door. Fury and disgust roiled in him - Rusty was passed-out drunk, Mr. Marvin surmised, as he walked up to kick his son's feet.

"Get up. C'mon, get up," he said, then grabbed Rusty's arm.

The chill of it, the quiet in the garage: Something stole all the fury away.

"When I flipped him over, I knew," Mr. Marvin said, remembering Rusty's wide-open eyes. In a corner sat a rolled-up dollar bill, an ID card flaked with white, and a CD case topped with what authorities later determined was $300 worth of cocaine - bought the night before with funds from an ATM.

With a lunge, Mr. Marvin bent down, his mind snatching one crazy thought from many: rumors of several teenagers who had hanged themselves in recent weeks. One hand darted to Rusty's neck, searching.

Instead of a rope or a scar, he found a crucifix, the single accoutrement Rusty always wore, even to bed.

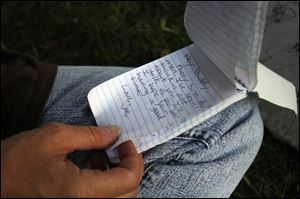

Amy Adams studies a notebook that is left on her son Rusty s grave for visitors to leave their thoughts in.

Hailey, Rusty's 16-year-old sister, woke to a sharp, sudden sound. Sitting up in her bed, she glanced out her bedroom's second-story window. Police cars packed the driveway.

Darting to the next window, she saw her brother's legs - his father and a police officer kneeling over him - and ran downstairs, too shocked to cry or even think.

An hour later, Mr. Marvin remembers the words of a police officer he now considers kind, as medical personnel worked on Rusty's limp body.

"I'm going to save you $20,000 and a ton of heartache - he's gone," said the officer, before being quickly chastised by a partner.

After his family prayed over him, Rusty was pronounced dead. A coroner's report later found 21 times the toxic level of cocaine in his system.

Rusty's mother remembers vividly the day Rusty grabbed her religious necklace - a day the teen spoke of with great reverence in the St. John's prayer group he'd started. A day his father says he will always regret.

The way Rusty told it at St. John's' intensive senior retreat, he was high with a friend, sitting in a car at the St. Ursula Academy parking lot. A man poked his head in the car window.

"Don't I know you from church?" the man asked, before departing with a heartfelt, if hurried, "God bless you."

Rusty, who had taken to attending Sunday Mass on his own, saw it as a sign. "The man was God, and he was telling me he loves and cares about me," he wrote in his journal that night.

"He thought God was trying to send him a message. He was real open about it; he talked about it in front of his whole class," said John Patrick Nichols, a close friend of Rusty's at St. John's who drove him to school.

"He always wanted to find meaning in things," said Kathleen Marie Martin, another close friend who went to St. Ursula. "He thought the drugs brought him closer to God."

Once home, Rusty came to his mother, grasped her necklace, and read the inscription inside, one they both knew. Matthew 7: Seek, and ye shall find. Knock, and it shall be opened unto you.

Ms. Adams was surprised by her son's intensity. "This is it! This is what it's all about!" he told her.

Mr. Marvin, on the eve of his 40th birthday, returned home to find his son in a state he personally knew all too well. They fought.

"Dad - Jesus loves you," Rusty said as the family pulled them apart.

The next year, Rusty organized an in-school prayer group at St. John's after imploring his counselor, the Rev. Frank Canfield, several times for permission.

"It was the first sustained prayer group that I can remember," Father Canfield said.

In that prayer group, Rusty's friend John recalls, members would often rail against Rusty's confessions of drug use.

"He was a leader among his classmates. He was well-liked. He did well in every manner of test," said Byron Borgelt, St. John's associate principal who noticed Rusty's volunteer work. Among other things, Rusty helped found the school's St. Patrick's Day soup kitchen.

"Rusty certainly went beyond what most kids would ever have conceived of doing," he said. "His senior year, it seemed like everything was clicking."

One play remains in St. John's football coach Doug Pearson's mind to this day: a 26-yard screen pass Rusty caught during a City League feud against rival St. Francis de Sales at the University of Toledo's Glass Bowl.

"He was quick, and he could cut real well. Really strong for his size. Kept slugging away," Coach Pearson said.

During the 2004 regular season, Rusty, a senior running back, averaged 6.9 yards a carry, a total of 582 yards, and scored nine touchdowns.

"I didn't really have a clue until he died he was into what he was into," Coach Pearson added. "Nobody was more shocked."

Those words are mimicked by other St. John's officials, even after Rusty went into several drug-treatment programs.

"It looked to me that he was working through his issues on his own and asking for help when he needed it," Mr. Borgelt said.

"It didn't appear to any of us that the problem was nearly as bad as what it was."

The family caught their first solid whiff of problems at the end of Rusty's sophomore year, when he was caught with a group of friends high and "garage hopping" - darting in open garages to steal beer from refrigerators. He was forced by his parents to enroll in Toledo Hospital's drug outpatient program.

At the beginning of his junior year, Rusty was caught on school grounds smoking marijuana and had a pipe in his pocket. School officials suspended him for five days and required a professional drug-treatment assessment. No criminal charges were brought.

In hindsight, family members say the punishment should have been harsher.

"We were very upset that they did not handle it more severely. Not just [St. John's] - us, the whole family," Ms. Adams said. "Who knows if it would've made a difference?"

"I think in this case the school went over and above what you can expect. I mean, after all, it's a family's responsibility to step up and be involved," said St. John's spokesman Gail Christie.

Mr. Marvin remembers getting a call about the incident from Mr. Borgelt.

"He told me, 'I don't even know what pot looks like,'●" remembered Mr. Marvin, who assured the first-year associate principal that he'd educate him when they met.

"There's so many things I forget in this job - but that meeting, I remember every detail," Mr. Borgelt said.

In a theology class essay, Rusty wrote that after Christmas, 2004, he partied "anytime and anywhere."

By April, less than three months before his death, he was enrolled in FOCUS, a Toledo inpatient program, and was pulled from St. John's to study from home.

By the start of last summer, Rusty "was not very reachable, not communicative," Father Canfield said.

Rusty's sister, Hailey, remembers driving to a party, sitting in a backseat with the older brother she adored as he pulled out some powder.

"Do you mind?" he asked. She left the car without a word.

As for why Rusty continued to use, Father Canfield said: "That's beyond me. What you don't know can really hurt you. It destroys.

"It hit me hard," he said.

Rusty's funeral at Christ the King Church in West Toledo was packed with hundreds of St. John's students, teachers, and parents. Every pew was filled; folks stood in the aisles, listening to the St. John's Men's Chorus echo off the church ceiling.

Mr. Borgelt said the incident with Rusty, and other youths, prompted him to strengthen the Jesuit school's written substance-abuse policy, mandating that all offenders undergo a professional assessment.

"There's just so many things with Rusty. [It was my] first year in this role and all that happened. It influenced a lot of what I do with this now," he said.

Father Canfield left St. John's last year after 15 years as a counselor - urged to take time off for a health sabbatical. He said he will not be returning to the school this fall.

After finding his son dead on his two-month anniversary with AA, the coins Mr. Marvin earns for his sobriety have lost much of their luster.

"The months don't mean [a thing] to me now," he said.

Across the kitchen table, Ms. Adams shot back: "They mean a lot to us." Hailey looked down.

Mr. Marvin did take the coin he earned in May for a full, drug and alcohol-free year.

Rusty's room remains much as he left it. On the door is a sticker: "Life is short. Party Naked." And on his bedspread: "The Lord is my shepherd. I shall not want."

His mother enters daily to dust. His father has only ventured in a couple times. "I don't go up there," he said.

Though Mr. Marvin believes otherwise, Ottawa Hills police Lt. Robert Kolasinski said he found no evidence of others being in the garage that night and had no solid leads of who may have supplied the drugs.

Lucas County Coroner James Patrick said that though Rusty had been on medication for depression, a fact noted on a police report, there was little doubt the death was anything but an accident.

"They're buying the stuff out on the street and have no idea how potent it is," Dr. Patrick said.

"With cocaine, you can take a small amount and get into trouble."

Mr. Marvin now devotes much of his time trying to build a house around his son's story and name - a support center called Rusty's House - for others to learn the lessons of his family's loss.

"As soon as we put him in the grave, we started that day," he said. "It took my son's death to get me sober."

Struggling for a foothold on a mountainous road to redemption, Mr. Marvin now speaks multiple times a month at churches, interventions, town hall meetings, and even occasionally at St. John's.

Rusty's House has two weekly support groups, one for parents of children with drug problems, and one for teens, both at Monroe Street United Methodist Church on Wednesday nights.

Ms. Adams visits Rusty's grave, usually once a day. At times she reads his journal and theology essays, keeping a draft he composed his senior year on top:

"The sober lifestyle may not have lasted too long, but my relationship with God never ended."

Contact Tad Vezner at:

tvezner@theblade.com

or 419-724-6050.