Lockdown drills helps schools train for trouble

2/26/2007

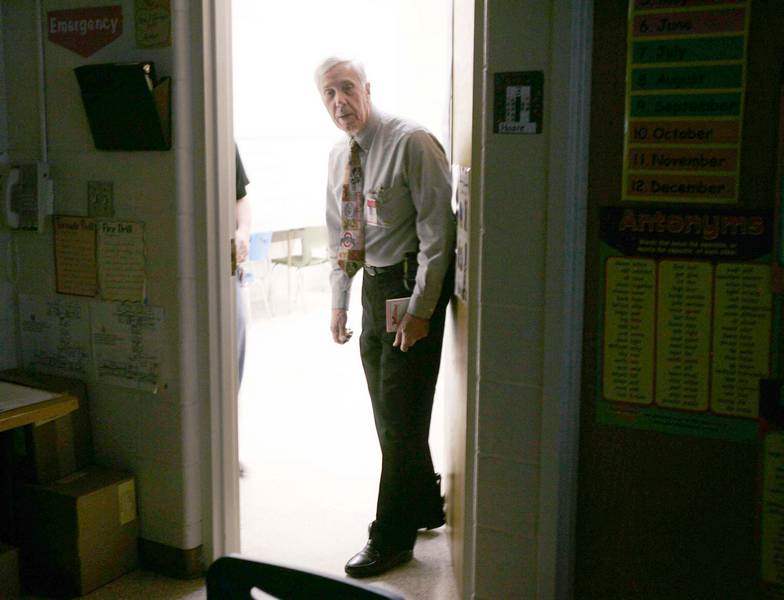

Gary Keller, principal of Kenwood Elementary in Bowling Green, inspects classrooms during a lockdown drill to ensure students and teachers are following proper procedures.

Third-grade teacher Mary Ann Hoare, far left, and her students at Kenwood Elementary in Bowling Green sit quietly during a school lockdown drill.

BOWLING GREEN - With hushed excitement, 15 third graders sprung from their seats when they heard the principal announce that their school was having a lockdown drill.

Math lessons forgotten, the youngsters hurried to the back wall of the classroom, dropped to the floor, and huddled together, sitting Indian-style. Their teacher quickly closed the curtains, covered the narrow window in the classroom door with construction paper, and locked the door before turning out the lights and joining the children on the floor.

It was Kenwood Elementary's first lockdown drill, a procedure that is being repeated at schools all over Ohio and Michigan, in many cases for the first time this school year. Both states passed laws last year that mandate the safety drills to prepare students and staff for the very real possibility of an armed intruder entering a school and firing at whoever comes into view.

Bowling Green teacher Mary Ann Hoare ushers her third-grade students into the area of the classroom used for lockdowns.

The purpose of the drill was not lost on Mary Ann Hoare's third graders at Kenwood.

"If somebody comes in here and they had a weapon, we wouldn't want them to kill us," 8-year-old Kelsey Hetrick calmly explained after Tuesday's drill.

Nine-year-old Michael Shilling said he wasn't scared.

"It's better to know what do just in case it really did happen," he said, adding that he "felt safe" huddled out of sight with his teacher and classmates.

That is precisely the idea behind the drills, said Ohio Rep. Jim Hughes (R., Columbus), who sponsored the bill. He said the impetus for it came in part from an incident at a high school in his district in which a man in a bloody T-shirt walked into the building, announced he had AIDS, and threatened to throw a vial of his blood into people' eyes.

Gary Keller, principal of Kenwood Elementary in Bowling Green, inspects classrooms during a lockdown drill to ensure students and teachers are following proper procedures.

"In that case they were able to subdue him, but it was a confusing situation" for teachers, administrators, and students who didn't know where to go or what to do, he said.

With the safety drills, Mr. Hughes said, "People are ready in case we have an incident like this. Hopefully, God forbid, we never will."

Kenneth Trump, president of National School Safety and Security Services, a Cleveland consulting firm, said a growing number of states are requiring schools to hold lockdown drills.

"Ohio of course has a requirement now, Indiana is considering it, and I think it's a good idea," Mr. Trump said. "But far too many schools have lockdown procedures on paper but have not practiced those."

Some schools have hesitated on the drills because they might frighten children, Mr. Trump added.

"A lockdown in essence is nothing other than a reverse fire drill and both are meant to keep children safe," he said.

Toledo Public Schools hired a consultant this school year to review all security procedures, including lockdowns.

Interim Superintendent John Foley said students need to practice the lockdowns just like fire drills.

"It also gives students a comfort level that we are prepared," Mr. Foley said. "And just like we do fire drills, students get better the more we do them."

Lagrange, Riverside, and Chase elementary schools were put on lockdown Wednesday as police hunted for the assailant in the shooting early that morning of a Toledo police officer. Mr. Foley said the measure was taken after police told them they would have heavy patrols in the area.

Start High School Principal Ray Russell said schools need to be ready for the worse-case scenarios.

"We've always had the tactic in place as far as having lockdowns," he said. "Does it make us safer? I think it helps us be prepared for situations that come up and we all hope that we never have to experience a situation where we have an intruder."

Ohio's new law requires schools to adopt school safety plans and submit a copy of the plan along with their building's blueprints to their local law enforcement agency and the Ohio attorney general's office.

While the new Ohio law requires schools to conduct one lockdown drill a year, Michigan schools must hold two such drills each school year. The law allows them to reduce the number of fire drills they do each year from eight to six.

For at least some school districts, including Bedford and Monroe, the new law has not had a big impact because they had a procedure in place and had been practicing.

Monroe High School Principal Ralph Carducci said his school has conducted such drills for at least three years.

"I think the whole Columbine thing put all that into effect," he said.

In 1999 at Columbine High School in Colorado, two armed teens killed 12 students and a teacher and wounded 24 others before shooting themselves to death.

"We do them at least twice a year and we try to create different scenarios. We'll make an announcement for a lockdown and then pull the fire alarm to see what they'll do," Mr. Carducci said

During the drills, school administrators walk the halls to make sure all doors are closed and locked and to make sure all students and teachers are out of sight. Safety gates in the hallways come down, keeping any members of the public inside or outside.

"We've gotten to the point that they understand we're serious about what we're doing," Mr. Carducci said. "When we have a lockdown, we don't see anyone in the halls."

At a training session last week for Kenwood teachers in Bowling Green, police officer Noel Crawford reminded them not to answer a knock at the door during a lockdown. He said they should keep their cell phones with them in case school officials or police need to reach them, but that they should try to keep students from using cell phones.

While Ohio schools hold monthly fire drills as well as tornado drills each month during tornado season, Liz Frushour, a Kenwood Elementary teacher for 20 years, said she doesn't mind the addition of the lockdown drills.

"I think it's essential in this day and age," she said, adding that no one thinks a shooting or other dangerous situation will happen at their school. "That's what everybody says after the fact. I think it's better to be prepared than to panic."

Kenwood Principal Gary Keller said he and his staff planned to dissect their first such drill at their next staff meeting. He said some teachers might have been disturbed by the 20 minutes lost because of the drill. Fire drills take only about 3 minutes, while tornado drills might consume 10 minutes, he said.

"It did take an extended amount of instructional time, but on the other hand it taught the kids to be quiet for an extended period of time," Mr. Keller said.

That clearly was a challenge for the students at Kenwood.

Mrs. Hoare reminded her class afterward that they must try their hardest not to talk, giggle, or cough during a drill.

"If someone is out in the hallway and they would hear a giggle or a cough, they would know we're in here," she told them after the drill. "So when we go through this drill, we have to be absolutely quiet."

Bowling Green Police Lt. Tony Hetrick, who observed the drill and checked classrooms with Mr. Keller, said the building was startlingly silent.

"You would have never known school was in session," he said.

Staff Writer Ignazio Messina contributed to this report.

Contact Jennifer Feehan at:

jfeehan@theblade.com

or 419-353-5972.