Compromise averts dustup over Native American relics in Ottawa County

4/20/2008

Brian Redmond, left, of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History brushes soil from artifacts at the site in 2004.

MARBLEHEAD - A gated housing development under construction.

Buried remains of Native Americans that are thousands of years old.

Archaeologists who want to study the artifacts, tribe members who want to see the bones laid to rest, and a developer who wants to see construction completed.

The story of the remains found in 2003 at The Cove on the Bay, an upscale development in Ottawa County, has all the potential elements of a conflict - yet it has been resolved with a compromise.

In 2003, construction was halted temporarily when bones were found on the site during a utility excavation.

Now many of the bones - after first having been studied by archaeologists - have been reburied in the ground. Other remains will be returned later this year.

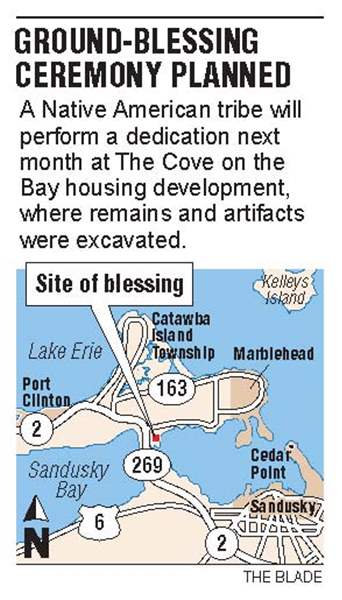

And next month, leaders from the Wyandotte Nation will perform a dedication and ground-blessing ceremony at the site. The development off Danbury North Road is designed for 81 lots, 25 of which have been sold, developer Greg Spatz said.

One of those homes belongs to Rebecca Schroeder-Perry, her husband, and two children. Among the first families to buy a residence in the development, Mrs. Schroeder-Perry said she is fascinated by the history so close to her house.

Mrs. Schroeder-Perry's children have found arrowheads and other artifacts nearby.

"There's history right next to our house," she said. "We look at it as the natural sciences and history unfolding at our fingertips."

The site around Mrs. Schroeder-Perry's vacation home once was inhabited by groups of Native Americans, according to Brian Redmond, curator of archaeology at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Mr. Redmond led a team from the museum in excavations at the site during several summers.

In addition to the remains, the scientists discovered fragments of cooking pots, tools, spear points, food remains such as freshwater clam shells, and bones of deer, raccoons, and fish.

One of the more interesting finds was a large shell, about 1,000 years old, on a necklace, that came from the Gulf of Mexico. It likely traveled this far north from trade networks among various tribes, Mr. Redmond said.

"It is a rare thing to find in northern Ohio," he explained.

An attractive location

The area had been occupied intermittently dating back 5,000 years, he said, starting as a fishing camp, then evolving into a larger farming village as recently as 500 years ago. By the end, several hundred people could have been living there, he said.

Why did these early North Americans keep coming back?

The same reason why people want to live in the Ottawa County area now - proximity to water and its resources.

"[It's] a great fishing area," Mr. Redmond said. "Marshes along the lakeshore were loaded with ducks and geese. This was a great place to live, and I think they must have liked it for a lot of the reasons that people do nowadays."

Building on the Danbury Township development was halted in 2003 after bones were unearthed during a utility excavation.

The scientists' dig at the "Danbury site" - so named because it is in Danbury Township - focused on lots in one end of the development that essentially were a cemetery area, Mr. Redmond said.

Being able to study a site where people lived in one spot for a long period tells archaeologists how a culture changes over time - in this case evolving from a transient fishing camp to a stable farming village.

This was an important shift in human development, said David Snyder, archaeology reviews manager for the Ohio Historic Preservation Office.

"This is a major, significant transformation in how people lived. There is a good bit of information from what we have learned at the Danbury site that is applicable to this transformation," Mr. Snyder said. "It was a pretty special site, for sure."

Among the finds

" rel="storyimage1" title="Compromise-averts-dustup-over-Native-American-relics-in-Ottawa-County-4.jpg"/>

Among the finds

" rel="storyimage1" title="Compromise-averts-dustup-over-Native-American-relics-in-Ottawa-County-4.jpg"/>

Rebecca Schroeder-Perry and Greg Spatz study a casting of a shell found at his housing development. <br> <img src=http://www.toledoblade.com/assets/gif/TO17150419.GIF> VIEW: <a href=" /assets/pdf/TO43962420.PDF" target="_blank "><b>Among the finds</b></a>

The area was first noted to contain likely human remains in 1977, in a statewide archaeological inventory maintained by the Ohio Historic Preservation office, he said.

Mr. Snyder estimates Ohio has about 43,000 archaeological sites, though many have only small amounts of artifacts.

Preserving history for study isn't always easy, he noted. There is no state legislation in Ohio to set up a process for review of how development should proceed when it impacts cultural resources.

The site and artifacts are treated as the private property of the owners, he said.

The remains did not fall under the jurisdiction of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, a law passed in 1990 that required museums and certain federal agencies to return some items to tribes for reburial.

The question of who owns the past has not always been an easy one for scientists and Native Americans to resolve. A skeleton found in Washington state in the 1990s, known as "Kennewick man" because of the area in which it was found, became the subject of a long-running legal dispute between Native American tribes and scientists.

Mr. Spatz credited his brother, Gary, who died in December and was his partner in the project, with making sure artifacts were studied and ensuring the bones were properly honored.

"Gary said, "I'd rather not make any money on this project and do the right thing,'•" Mr. Spatz said.

Mr. Redmond said he is grateful for Mr. Spatz's permission to explore the site, something the developer had no legal obligation to let the museum do.

Brian Redmond, right, directs the excavation of a test unit. They have been able to follow the evolution of a transient fishing village into a stable farming community.

"He has been exceptional in his willingness to preserve the site, and allow us to do the excavation," Mr. Redmond said.

The Wyandotte Nation, a tribe of about 4,500 people based in Oklahoma, is handling the reburial, though the tribe's members are not the descendants of the Native Americans who lived on the site.

"We don't know who the descendants of these people are," Mr. Redmond explained. The early residents left about 1600, before contact with the Europeans, possibly because of conflict with another tribe, such as the Iroquois.

The Wyandotte did live in Ohio at one point, but it would have been after the group living on the site already had left. The tribe is still interested in seeing the bones returned to the earth, said Sherri Clemons, cultural events coordinator for the Wyandotte Nation.

"They are somebody," she said. "And they need to be put back. They need to be put back on their journey, whoever they are."

The bones have been reburied in a green area with a perpetual easement to prevent development, Mr. Spatz said, and the tribe purchased several lots containing remains that they will keep as green space.

"And I learned a lot about the Native Americans and their beliefs and their culture," Mr. Spatz said. "They are part of the Ohio heritage. A lot of people think of Ohio as only going back 200 years, but the Wyandotte have been here thousands of years."

The Wyandotte Nation was contacted several years ago by a Native American group in Ohio when bones were found at the site.

"They were concerned that [the bones] had been found and were being dug up and they felt they were being disrespected," Ms. Clemons said.

It made sense for the Wyandotte to get involved since they had a historical presence in this area of Ohio, she said. The tribe left Ohio in the early 1840s. Their land basically had been reduced to the area around Upper Sandusky, thought it was much greater at one time.

After being contacted about the bones, "we got ahold of the landowners and started discussing with them," she said.

"Once you talk to a developer and they find out you aren't going to shut them down or bring charges, you just want to do what's right, they were very easy to work with."

Ms. Clemons said a number of tribal members will attend the dedication and ground blessing ceremony at 10 a.m. May 28. The public is invited.

She anticipates the rest of the remains will be reburied before the end of the year.

For her part, Mrs. Schroeder-Perry said she doesn't mind having the bones reburied near her home.

"It's not a bad sensation," she said. "It's very peaceful."

Contact Kate Giammarise at: kgiammarise@theblade.com or 419-724-6133.