Lake shorebird rebounds from protected to pest

5/11/2008

A double-crested cormorant makes its home on Canada's East Sister Island. A cull is likely to take place on the island to reduce the birds' numbers.

A double-crested cormorant makes its home on Canada's East Sister Island. A cull is likely to take place on the island to reduce the birds' numbers.

EAST SISTER ISLAND, Ont. - If pigs could fly. ...

They might be confused with dark-colored birds called double-crested cormorants.

Right or wrong, no Great Lakes bird seems to have moved so quickly from victim to villain in the public's eye.

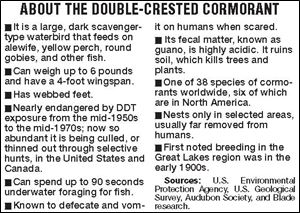

Pushed to the brink of extinction a generation ago, the double-crested cormorant - one of 38 types of cormorants worldwide and six in North America - now wreaks havoc on small, uninhabited islands in western Lake Erie.

At least that's how many Great Lakes wildlife managers and sportsmen view them.

To animal rights activists, though, the birds have been shamelessly persecuted by humans for several decades because of their smell and the unsightly messes they have left behind - and to placate those who believe they're a threat to the fishing industry.

Like the bald eagle, the double-crested cormorant was a symbol of poisoning by DDT and other chemicals associated with the post-World War II industrial boom.

Not any longer. It has bounced back in such numbers that biologists and sportsmen now view it as a scourge that needs to be thinned out.

Some managed hunts - "culls" - by sharpshooters have been conducted during the last two years on the American side of Lake Erie, at West Sister Island, Green Island, and Turning Point Island.

Additional culls have been staged along other Great Lakes, on both sides of the border.

West Sister is in an isolated part of the lake between Toledo and Catawba Island, some nine miles north of Jerusalem Township. It is a wildlife sanctuary the federal government owns, home of the most important colonial wading bird colonies on the Great Lakes. Those include great blue herons and black-crowned night herons, as well as great, snowy, and cattle egrets.

Green and Turning Point islands, both to the east, are managed by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources. Each has restricted access.

On May 1, Canada responded to culls on the U.S. side of Lake Erie by sending its own sharpshooters to Middle Island, which is south of Pelee Island and is Canada's southernmost strip of land. It previously had culled birds from Presqu'ile Provincial Park in eastern Ontario, on the northern side of Lake Ontario.

Middle Island is now off-limits to visitors until Sept. 1. Attention is soon expected to shift to another Canadian island in Lake Erie that has been devastated ecologically, East Sister Island.

Marian Stranak, Point Pelee National Park of Canada superintendent, which oversees Middle Island, said the Canadian cull is the backbone of a five-year management plan calling for a fivefold reduction in Middle Island's population of 5,000 cormorant pairs.

On the U.S. side, the Ohio DNR said culls have cut the cormorant population on West Sister Island nearly in half, from 3,813 pairs in 2005 to 1,967 pairs in 2007. The number on Green Island declined from 857 to 686 during that time period, while more than doubling, from 409 pairs in 2005 to 934 pairs in 2007, on Turning Point Island.

Cormorants don't just multiply rapidly. Their highly acidic droppings ruin island soil.

Countless trees have died and native plants have disappeared. Other birds have abandoned their nests, feeling the pinch of a dominant species.

But are the cormorants to blame? Or are we?

Mark Shieldcastle, wetlands project leader at Ohio's Crane Creek Wildlife Research Station in Ottawa County, said a lot of the problems people encounter with wildlife these days - whether it's an abundance of deer in Maumee or cormorants in Lake Erie - is simply a reflection of excessive development.

"It's a symptom," Mr. Shieldcastle said. "We really shouldn't be looking at the cormorant as the problem. The problem is the lack of habitat, which puts that much more pressure on wise management of the habitat that's left."

Symptom or not, Mr. Shieldcastle is one of several U.S. and Canadian scientists caught in a race against time.

In less than two decades, the scientists have gone from fretting over the cormorant's future to thinning out colonies in hopes of keeping the bird's population from spiraling out of control.

Mr. Shieldcastle said it would be irresponsible to be complacent. Left unchecked, cormorants will destroy more trees and plants.

The result would be a gradual loss of other forms of life, which would mean less biological diversity, he said.

Liz White, director of the Toronto-based Animal Alliance of Canada, said the islands are being overly managed to meet unrealistic expectations for them, based on eras in which cormorants were artificially suppressed.

Had it not been for the intentional slaughter of them and their exposure to lethal pesticides, the islands likely would have evolved differently, she said.

"You can not surgically manage a species in a confined area," Ms. White said, arguing that the controls are done to appease people and not because of scientific justification.

"What those islands look like now is a human-induced look," she said.

Jerome Tinianow, Audubon Ohio vice president and executive director, said culling is a "complicated issue" his group has debated internally, though he said it has been willing to work with the Ohio DNR and is trying to remain open-minded.

The group would like Ohio to reassess its actions now that allegations have been raised about some culling practices in Canada. "We're just at the point of asking the questions," Mr. Tinianow said.

Chip Weseloh, head of Environment Canada's wildlife toxicology, said few cormorants existed in the Great Lakes basin in the early 1900s. By the 1950s, 1,000 pairs were across the region.

Like bald eagles, they had trouble reproducing after ingesting prey contaminated by DDT, a pesticide banned in the 1970s because of myriad health problems associated with it. DDT made bird egg shells too thin.

There now are an estimated 215 colonies and 115,000 pairs of double-crested cormorants across the Great Lakes, Mr. Weseloh said.

"They're very opportunist and take advantage of what's available," he said.

Mark Ridgway, an Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources biologist, said cormorants have thrived in large part because of the changing mix of Great Lakes fish.

"They never had fish come to them like they do now," he said.

One example is a little fish from eastern Europe called the round goby. It's now so pervasive it's "almost dandelionlike," Mr. Ridgway said.

Gobies, one of 183 known species from other parts of the world to have invaded the Great Lakes, feed on zebra mussels and quagga mussels. The mussels came from the same part of the world as gobies, via the ballast water of international cargo vessels about 20 years ago. Gobies soon followed.

Biologists say there are literally billions of mussels and gobies in western Lake Erie.

That's given cormorants a well-stocked lake from which to feed.

Cormorants are scavengers with a unique ability to dive 70 feet below a lake's surface, more than deep enough to reach the shallow bottom of western Lake Erie. The birds can stay underwater up to 90 seconds at a time. That gives them enough time to forage the lakebed for gobies and other fish.

The birds winter in the Carolinas and other parts of the South, where they are known to trespass upon fish farms and fatten up on catfish.

The controversy has inspired another Toronto group, the Peaceful Parks Coalition, to strike back. It has called for a boycott of Point Pelee National Park in hopes of cutting into the revenue of Parks Canada, the federal agency in charge of Canada's cull.

Contact Tom Henry at:

thenry@theblade.com

or 419-724-6079.