Dream of reunion endures

12/25/2000

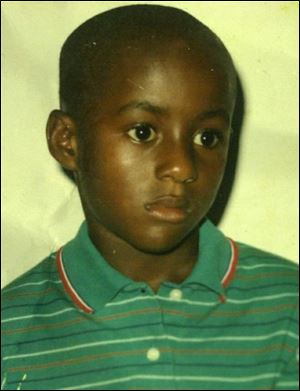

Francis Nmah, 9, whose student visa to join his family in this country was denied, remains in Liberia. `We don't feel right - our son's there, and our families are there. It's not easy,' says his father, Gabriel, who came here in 1998 with his wife, Margaret.

As Gabriel and Margaret Nmah celebrate Christmas this morning, their hearts and minds will be thousands of miles away in their native Liberia, where their 9-year-old son remains trapped by federal immigration law.

The Nmahs' hopes for their son, Francis, to join them for the holidays have been dashed, but growing political and community support have encouraged their dreams of being reunited.

The family has been separated since Mr. and Mrs. Nmah arrived in America in 1998 to escape the poverty and hunger caused by a six-year civil war. Mrs. Nmah had won a visa lottery and had to use it before it expired.

She could have brought Francis, but couldn't raise enough money for them all to make the trip. As it was, her mother used most of her savings for the couples' visa and travel expenses. The Nmahs were reluctant to leave their son, but they were told by a U.S. Embassy official in the unstable West African country that the boy could get a student visa as soon as they had the extra money to send for him.

The information was wrong. Francis's student visa was denied in 1999, and the Nmahs haven't seen their boy since they left to make a better life for themselves. In July, the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service rejected a request for humanitarian parole, under which people are granted entrance to the country when there is a compelling humanitarian need.

Mrs. Nmah berates herself for leaving Francis and said she sometimes considers herself a bad mother. She said she never would have left her son had she known it would be so hard to get him into America.

She left only when her family and friends told her it was the right thing to do so they could earn enough money to send for the boy.

“Coming to America is like going to heaven,” Mrs. Nmah said. “If one person can go, it's special for the whole family.

“The conditions back home are very, very critical. There's no water; there's no food. My people are always calling saying they need money for food,” she said.

Since The Blade reported the family's troubles in a Nov. 30 story, U.S. Sens. Mike DeWine and George Voinovich, Ohio Republicans, wrote a joint letter to immigration officials in Rome asking them to reconsider the denial of humanitarian parole.

U.S. Rep. Marcy Kaptur (D., Toledo) has been involved since summer and has written letters on behalf of Francis.

Some local churches and employees at Pro-Pak Industries, where Mr. Nmah works, have become involved, participating in a petition drive that expresses support for the family.

Advocates for Basic Legal Equality is sending the petition to the immigration service.

It is unclear whether the political and community pressure will make a difference. In July, Dennis Peruzzini, acting director of the immigration service's Rome office, wrote a letter saying the facts in the case are unfortunate, but “do not constitute circumstances that would place the applicant in an urgent humanitarian category.”

Emiko Furuya, a fellow with the National Association of Public Interest Law who works in the Toledo office of the Advocates of Basic Legal Equality, said it makes no sense to keep Francis out of the country when he will be eligible for entrance in four or five years if his parents gain citizenship.

She said she doesn't understand how Francis doesn't meet the standards for humanitarian relief. Not only is he separated from his parents, but Liberia is growing increasingly unstable, she said.

Ms. Furuya said she's afraid that if the fighting that ended in 1996 resumes, Francis might get sent to a refugee camp, and his family could lose track of him.

The boy is living with Mrs. Nmah's sister, but the family could be uprooted if conditions become dire. Mr. Nmah said just getting enough to eat is a daily struggle for most people. Jobs are hard to come by and medical treatment is unavailable without money, he said.

“We're scared because we don't know what's going to happen,” Mr. Nmah said. “We don't feel right - our son's there, and our families are there. It's not easy.”

The Rev. Martin Donnelly, the pastor of St. Martin de Porres church, which the Nmahs attend, said the couple has been strong, but it's been painful for them to be separated from their son.

“I think they feel somewhat incomplete without Francis,” said Father Donnelly. “They're better prepared to raise him - better than anyone else.”