Pressure slowed by flowing hydrants

6/12/2002

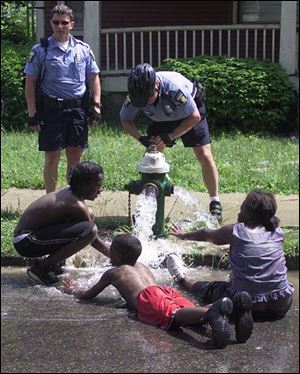

Officer Greg Mahlman watches Tysean Haynes, 13, Regan Williams, 10, and Candance Haynes, 12, from left, enjoy a final splash from a hydrant on Cumberland Street as his partner, Officer Bill Michalski, turns off the water.

Throughout Toledo yesterday, more than 40 fire hydrants spewed water into the streets. The idea: With no open city swimming pools, just make your own.

But that causes problems for neighborhood residents, the city's water department, and firefighters.

“Fire hydrants are used in a lot of neighborhoods where people don't have access to other recreational resources for cooling down,” said Deputy Fire Chief Robert Metzger, head of operations for the department.

When Toledo pools open Tuesday, the number of open hydrants likely will decrease. But it will affect only those places where a pool is nearby. For most neighborhoods, the problem will last throughout the summer.

“If we have a lot of these open hydrants in a particular area of the city, it really impedes our ability to handle a large fire,” Chief Metzger said.

According to the water department, 68 hydrants were open Monday and 41 by 6 p.m. yesterday, which officials said is typical for this time of year.

In the past, there have been situations where open hydrants have hindered firefighters enough that blazes spread beyond the structures where they originated, Chief Metzger said. “It certainly does happen, and it's predictable that it will happen when the fire hydrants are used in an illegal capacity,” he said.

Tampering with a fire hydrant, according to the Ohio Revised Code, is a fourth-degree misdemeanor, which upon conviction carries a maximum penalty of 30 days in jail and a $250 fine.

Still, few people are punished.

Typically, water or fire employees close hydrants' valves and try to reason with the people who either opened them or were splashing through their spray. “We discourage it as strongly as we can,” Chief Metzger said. “We're not trying to create a confrontational situation. We just wish people would do one of two things: Set up a sprinkling device in their own yards or go to a pool.”

But for neighborhood residents like Rosanna Stuber, the effects of opening a hydrant are distracting and annoying. She can't use the dishwasher or the washing machine or take a shower - there's just not enough water pressure, she said.

The hydrant in front of her house near Fulton Street and Melrose Avenue flows freely throughout the summer.

She calls the police, water, and fire departments to report the problem. Sometimes, she said, the water department comes and turns it off, but other times her husband does it. Just turning it off isn't the answer because usually it's turned right back on, she said. It's a problem she's dealt with since she moved to the neighborhood three years ago.

Drivers are constantly honking at children in the street. Mixing wet pavement and children just increases the chances for an accident, she said. Still, that's not the only way someone in the street while a hydrant is spraying can get hurt.

When the largest valve on a hydrant - typically, the one that faces the street - is opened, unrestricted water flows from the hydrant under high pressure.

“That's my biggest fear - that in the process of just trying to cool down and have fun, kids are going to get hurt,” Chief Metzger said.