A fraud ahead of its time

2/9/2003

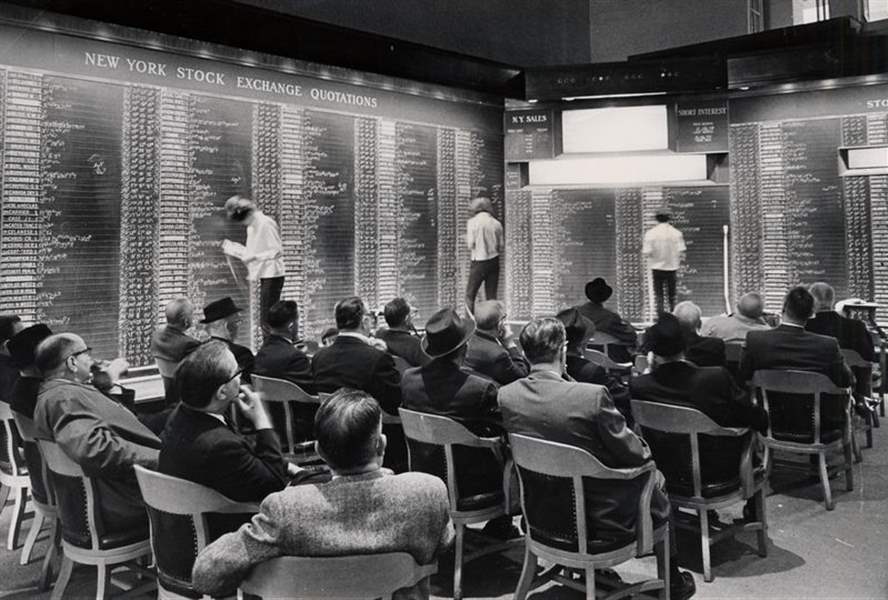

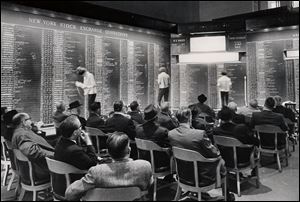

Bell & Beckwith's ticker room was a popular gathering spot in the mid-1960s.

blade

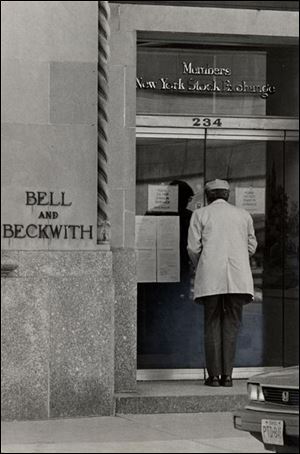

One of Bell & Beckwith's 7,000 investors peers through the brokerage's locked doors after regulators discovered the embezzlement of $47 million.

Twenty years ago Toledo was in the midst of a shocking week. On the bitter-cold morning of Monday, Feb. 7, 1983, the 85-year-old Bell & Beckwith brokerage firm failed to open.

Customers found the Erie Street building's plate-glass doors locked and were told by a guard that the brokerage was closed. By 9 that morning, the New York Stock Exchange made it official: Bell & Beckwith was suspended as a member.

Federal regulators had swooped down on the venerable brokerage in an extraordinary series of events that included an unusual Saturday U.S. District Court hearing in a makeshift courtroom at a motel next to Toledo Express Airport. Regulators also closed Bell & Beckwith offices in Findlay, Defiance, and Lima.

Three days later, U.S. District Judge Nicholas Walinski appointed a trustee to oversee the brokerage, and the next morning, Friday, Feb. 11, the judge told a packed courtroom that Bell & Beckwith was insolvent and would be liquidated.

The brokerage failure, a notorious event in Toledo's business history, affected many lives. The news stunned 7,000 investors, many of whom feared their accounts totaling $110 million might not be covered by the Securities Investor Protection Corp.

The failure led to charges of fraud against Edward P. “Ted” Wolfram, Jr., the managing partner who embezzled $47 million and who served 10 years in federal prison, out of a 25-year sentence.

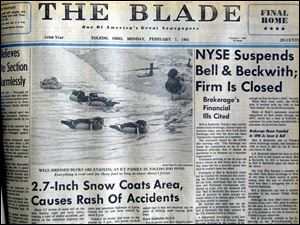

Headlines from The Blade.

It started a bankruptcy case that dragged on for 14 years. And for nearly 15 years, the failure remained the costliest in the Securities Investor Protection agency's history. It took time, but the federal agency made nearly all the investors whole by reimbursing their investment, but its costs totaled $30.7 million.

No one has to remind Ted Wolfram of the hurt, anger, and financial ruin caused by the failure. “What I did was terribly wrong,” Wolfram told The Blade in an interview last week. “I'm not saying, `Please forgive me.' You can't forgive what I did. I was a damn fool. I hurt a large number of people, and I lost my honor. You can't get that back. Everything that happened to me I caused. I spent 10 years in prison and deserved every minute of it.”

For the last decade, Wolfram has worked for Ethical Management Consultants, a California firm started by a Pepperdine University professor, lecturing groups of business people on white-collar crime prevention and counseling criminals facing long prison sentences.

“We talk to people and try to help them see what they're facing, so their families don't break up if they're going to prison,” he said. “We try to tell them if you do something, it's your fault.”

Some fallout from Wolfram's action rained down on his attorney, William Connelly, who said some people were angry with him for defending the Bell & Beckwith figure.

Mr. Connelly today is general counsel for the Medical College of Ohio and a partner in the law firm of Connelly, Jackson & Collier.

U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Richard Speer presided over the case for 14 years, more than half of his 27 years on the bench. More than 100 lawsuits stemmed from the brokerage failure, and the judge sorted through more than $132 million worth of assets before the case was closed.

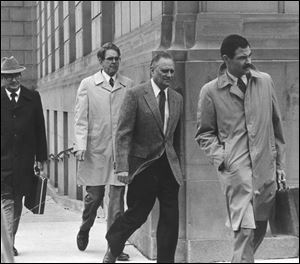

Edward P. Wolfram, second from right, leaves the federal courthouse in Toledo during his April, 1983 trial.

Judge Speer never met Wolfram, who caused the debacle. But he did get to meet several of Wolfram's seven partners, some of whom went bankrupt themselves after a $29 million federal judgment against them. He quoted from Don Corleone in The Godfather: “Hold your friends close and your enemies closer.” And “You can steal more with a briefcase than with a mask and a knife.”

The judge has seen many a business person ruined by a felonious partner. “The human condition hasn't changed in 3,000 years,” he observed.

“The rules of paying attention to what's going on never changed and never will.” Pointing to the collapse of Enron and Global Crossing, he said Wolfram “was ahead of his time.”

Ralph Buie, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission examiner who discovered Wolfram's fraud, learned from the experience. “Don't be misled by early indications of honesty and compliance,” he said. “Nobody could have been nicer than Ted Wolfram was during the examination. I learned to take a careful look at well-run companies when there's a strong executive. When red flags go up, dig deeper.”

He said he recalls telling his wife at the time that Wolfram was either the wealthiest man he'd ever met, or a crook. He turned out to be the latter. Mr. Buie retired from the SEC in 1996 and now heads Bradford Compliance Group, Inc., in Atlanta, a firm that does SEC-compliance consulting.

Bell & Beckwith's ticker room was a popular gathering spot in the mid-1960s.

By Feb. 4, 1983, Mr. Buie had been in Toledo 11 days, poring over the books of Bell & Beckwith, ostensibly a rock-solid firm, the last Toledo-based brokerage that had a seat on the New York Stock Exchange and an operation to perform stock transfers.

Wolfram had a dozen different brokerage margin accounts and had borrowed $32 million over a five-year period (or $47 million with interest) against what was purported to be $278 million worth of stock in Toto Ltd., a Japanese maker of plumbing fixtures, and what was supposed to be $105 million in convertible bonds.

The managing partner had acquired the 30-story Landmark Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas, where his wife ran a show-production company; a $2 million jet; two cattle farms in Arkansas and one in Missouri; a horse ranch in Florida and interests in race horses; part interest in an oil-exploration company; 17 sport and luxury cars; and a large home on the Maumee River in Grand Rapids designed by a disciple of Frank Lloyd Wright.

But Mr. Buie became concerned when Wolfram couldn't quickly produce documentation of the collateral. What he did provide appeared to be copies, not originals. The examiner was very concerned when he discovered a New York broker's “confirmation” of foreign stocks didn't tally - it was $8 million off. Mr. Buie kept pressing and discovered Wolfram's forgeries.

The original statement from the former Drexel Burnham Lambert in New York plainly showed that Wolfram's 2,816 shares of Toto were worth just $5,068. Two examiners flew to Las Vegas to verify the bonds held by a bank. More bad news: They didn't exist.

The SEC called Judge Walinski to arrange the emergency court hearing the next morning. By Saturday afternoon, Feb. 5, the judge ordered the closing of the four brokerage offices.

Even as the bankruptcy got under way that second week of February, Ted Wolfram was helping FBI agents find where the $47 million went. He was cooperating because he planned to plead guilty.

“It was the biggest dollar-amount fraud I had,” said Patrick Foley, the assistant U.S. attorney who prosecuted the case. “It was a colossal fraud that caused a lot of sleepless nights for thousands of investors, and life savings were [frozen]. But it wasn't the most difficult case [because] Wolfram pled guilty.”

Mr. Foley retired two years ago and is now a nominee for a vacant Lucas County Common Pleas judgeship.

Patrick McGraw, the Bell & Beckwith bankruptcy trustee and a partner at the time with the Toledo law firm of Fuller & Henry, recalled taking the case with trepidation. “This thing clearly was very big and very risky from a professional standpoint,” he said.

“Whoever was trustee was going to have to drop everything else immediately and work on nothing else for Lord knows how long.”

Now an investigator with the Ohio Civil Rights Commission in Cleveland, he said the brokerage failure caused lasting damage to the confidence and trust people would like to place in brokers. He fears the securities industry didn't learn enough of a lesson.

“Bell & Beckwith was an audit and regulatory failure,” he said. “Now, 20 years later, we have Enron. ... People like Wolfram will come along from time to time and take advantage of the lack of effect audit mechanisms and the lack of effective governance.”

Michael Don, president of the Securities Investors Protection agency, said Bell & Beckwith remains one of its biggest cases. Only three are bigger, all occurring in the last five years. The Toledo failure, he said, was huge in light of the fact that 75 percent of failures cost less than $1 million each.

Despite the debacle, he said regulators are usually pretty good at catching frauds before too much money is stolen. His agency recovered $7.7 million from Wolfram's properties (including $4 million for the Landmark, which was razed in 1994); $2.4 million from the other partners, and $6 million from auditing firms that failed to catch the fraud.

It took a while, but the agency returned funds to all investors except Charles McKenny, a wealthy Toledo lawyer and a personal friend of Wolfram.

Mr. McKenny, who died 13 years ago, had $8 million in the brokerage, and millions of that was tied up for years. Eventually his family got back all but about $400,000. Bankruptcy Judge Speer is convinced the turmoil shortened Mr. McKenny's life.

Wolfram recognizes his legacy, but said his latest work may be his salvation. “If I had died [20 years ago] I would have gone straight to Hell. This way I have a chance, just a chance to sneak in the back door of Heaven.”