Money woes at Cavista cited

3/14/2003

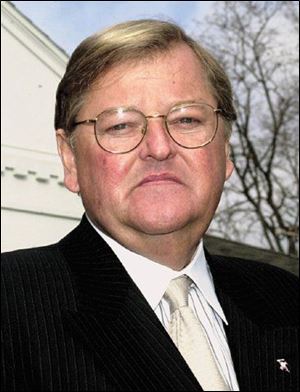

Edwin Bergsmark faces 12 counts of bad checks.

A former top executive of the defunct Cavista Corp. testified yesterday that the company was struggling financially months before checks paid to agents of the firm's realty company began to bounce.

David Boston, testifying at the trial of Edwin Bergsmark in Lucas County Common Pleas Court, said he began receiving calls from vendors as early as June, 2001, asking to be paid.

He said businesses that provided services and equipment, such as newspaper advertising and realty signs, were owed money. The former Toledo city manager said he loaned $50,000 to Mr. Bergsmark, but was never paid back.

“I was aware that money was very tight,” Mr. Boston said. “I knew we were short of cash.”

Mr. Boston was among the witnesses who told Judge Frederick McDonald that Mr. Bergsmark, former chairman and chief executive officer of Cavista, was desperately in need of cash to keep his real estate empire afloat.

Mr. Bergsmark, 61, of Sylvania, is charged with 12 counts of passing bad checks for allegedly writing commission checks he knew would bounce to Cavalear Realty agents.

Prosecutors said agents were stiffed for about $55,000.

The trial is being heard by Judge McDonald in lieu of a jury. He will decide whether the former banker and Toledo civic leader is guilty or innocent of the bad check charges as well as felony forgery and bribery charges.

Mr. Boston was president and chief executive officer of Cavista from March, 1999, until December, 27, 2001, when the real estate and development firm collapsed.

He said he was paid $225,000 annually to oversee the day-to-day operations of Cavista subsidiaries, including the real estate operations, which was the largest in northwest Ohio.

The bounced checks were authorized from accounts Cavista maintained through KeyBank, which had loaned more than $7.7 million to Mr. Bergsmark.

Dale Clayton of KeyBank said Cavista frequently wrote checks when it didn't have sufficient funds in the account to cover them.

When Mr. Clayton, who works at the bank's Cleveland office, was assigned to the account in October, 2001, the overdrafts were in excess of $300,000.

He said Mr. Bergsmark eliminated the overdraft amount several weeks later, but the problem soon returned.

He said the situation got to the point that KeyBank called Cavista daily to ask Mr. Bergsmark or other company officials to approve the checks they wanted paid, letting the others bounce.

“Cavista decided what checks they wanted to pay and what checks they didn't want paid,” Mr. Clayton said.

The situation with the overdrafts was alarming to KeyBank, and Mr. Bergsmark was told numerous times that the overdrafts had to end, he said.

At one point, Mr. Clayton said Mr. Bergsmark, asking for an overdraft in early December, 2001, told him: “I don't know what to do. If you return these checks, I am out of business.”

KeyBank sued Mr. Bergsmark for the $7.7 million loan he owed Dec. 13, 2001, about a week before KeyBank stopped allowing the overdrafts completely, Mr. Clayton said.

Three other banks - Sky Bank, Fifth Third, and Genoa Banking in Ottawa County - sued Mr. Bergsmark earlier in the month for $3.7 million in overdue loans.

By Dec. 27, all Cavista employees were laid off, and the company's Sylvania headquarters was shut.

Soon afterward, KeyBank assumed control of Cavista, shutting down the subsidiaries, and selling the assets.

John Kolpien, a consultant hired Dec. 4, 2001, by Mr. Bergsmark to save his company, testified he accessed Cavista's financial condition and determined it needed thousands of dollars in working capital to continue operating.

Mr. Kolpien, Mr. Boston, and William Conklin, president of Cavalear Realty, testified that the bulk of Cavista's profits were generated by commissions from property transactions, and they had to make sure the company's nearly 400 agents got paid or else they would leave.

“They needed cash. Quite a bit of cash for what was going to take place through the end of December through January,” Mr. Kolpien said. “The insufficient funds were a major concern.”

Compounding the problem, they said, was that December, especially the holidays, and January, were a slow period for home sales and it would take a large infusion of cash to keep the company going.

Mr. Clayton said he recalled that Mr. Bergsmark said the “business will die” if the agents didn't get their commission checks.

“If you didn't pay the real estate agents, then Cavalear and Cavista would dry up,” Mr. Clayton said.

Also, John Mangas and Kathy Kuyouth, former Cavalear vice presidents, left the company in November, 2001, to start a real estate company of their own, taking about 25 of Cavalear's top sales agents.

“The situation was critical,” Mr. Conklin said. “We were losing sales people, and income was going down.”

In need of additional funds, Mr. Boston said Mr. Bergsmark met with an investment firm in New York City in September, and left the day before the terrorist attacks.

In December, according to Mr. Kolpien and Mr. Conklin, Mr. Bergsmark tried to sell his interest in a partnership to raise money, and received offers to buy Cavalear Realty.

However, the offers, which included a $7.5 million proposal from a group of investors that included Mr. Conklin, were withdrawn.

Mr. Conklin said he and the investors changed their minds after learning the profit projections provided by Mr. Bergsmark were not realistic.

Testimony is expected to continue today.