Owners nurture Toledo's Gothic beauty

1/13/2004

The tallest of the turrets on the Pythian Castle, built in 1890 at Jefferson and Ontario streets in downtown Toledo, is 185 feet high.

She waits in stony, cold solitude, her elegance stubborn in the face of time, weather, and vandals.

The tallest of her Gothic turrets stretches 185 feet into Toledo s skyline, towering over the collection of more mundane buildings around her: a parking garage and a bus depot among them.

Thieves have stripped much of her metal guts. Weather has burst her pipes, rotted her beams.

Yet the Pythian Castle still intrigues.

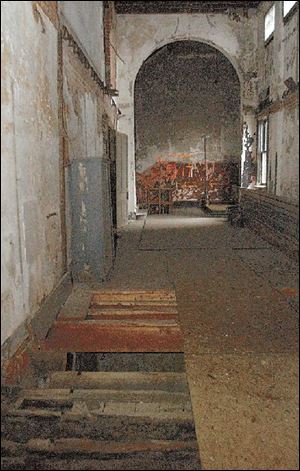

“That s one of those buildings I d chain myself to if there was ever any threat to tear it down,” said Kathleen Kovacs, executive director of Neighborhoods in Partnership. Yesterday, owner Brian Uram stood on the fourth floor, craning his neck to glance at the 20-foot-high arched entrance to the grand ballroom, lined with enormous windows.

Asked if he s frustrated with the building, he laughs, then shakes his head.

“I haven t given up on it yet,” he said. “I m not walking away.”

The Pythian, on Jefferson Avenue at Ontario Street, is one of downtown s oldest structures. Built in 1890 for the highly secretive Knights of Pythias, it housed the Knights meetings, ceremonies, and rituals, mostly on the upper floors, while the lower floors served as home to J.W. Green Co., a piano sales firm, until 1961.

A 20-foot high arched entrance to the grand ballroom on the fourth floor is one of the architecural features advocates say make the Pythian worth preserving. The building had its last tenants in the early 1970s.

The building went through a series of owners in the latter part of the 20th century, went into foreclosure, and fell into disrepair.

It had its last real tenants in the early 1970s, when Ed Emery, who has tried to unseat Congressman Marcy Kaptur several times, operated a gathering place for young people with a bent toward art and music.

Mr. Uram, in fact, is one of the most promising developers the building has seen since that time.

By the time Mr. Uram and another residential developer, the late Robert Shiffler, bought the building in 1997, its disrepair was so bad, it landed on former Mayor Carty Finkbeiner s list of the “12 most offensive commercial and industrial properties.”

Sold for $108,000 in 1989, the Pythian changed hands to Mr. Uram and Mr. Shiffler for a mere $4,500. The two put “more than a quarter-million dollars” into solidifying the old building, replacing its roof, and installing the rudiments of a new electrical system, Mr. Uram said.

As one stands near the building s entrance, a glance upward tells it all. Ragged holes in four layers of the floors expose what one shouldn t see from the ground floor: the underbelly of the roof.

“If someone had just taken care of the little things years ago, none of this would have happened,” Mr. Uram said, shaking his head.

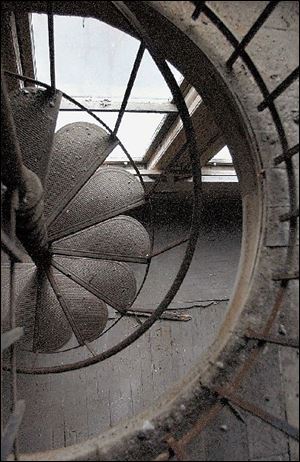

A curved stairway extends downward from the third-floor auditorium of the building.

Part of the problem too is the lack of parking. From time to time, developers and planners have discussed the possibility of moving the Greyhound station.

“If there were adjacent parking, that building would be snapped up,” said Steve Herwat, director of the Toledo-Lucas County Plan Commission.

He and others point to the building s unique design - not only the Romanesque sandstone exterior, but its unique interior layout. In its heyday, its design included several balconies, sweeping staircases, split-level floors, and even a walk-in safe that kept “paraphernalia and lodge jewels,” according to newspaper accounts.

Mr. Uram said he s taken steps to keep as many of the building s original pieces so they can be incorporated into its new design.

A third floor stage still stands in the large auditorium, ringed by pieces of a balcony. Shreds of the building s original aesthetics lie on the floor: pieces of cornice, piles of ceramic tile, squares of punched tin exterior artwork.

Oak handrails follow the flights of stairs that lead to the 20-foot high arch, the entrance to the grand ballroom on the fourth story, where balconies once swept the length of the floor.

The imposing turret reaches upward, its highest point from the inside vanishing inside its own airtight darkness.

Mr. Uram said he s had inquiries from time to time about the building, but nothing serious in recent years.

“Downtown is slow right now,” he said, “but things are going to look up in the next two, three years. It just needs the right person.”