SCENES FROM THE PAST

Blade played integral role in zoo's history

3/13/2005

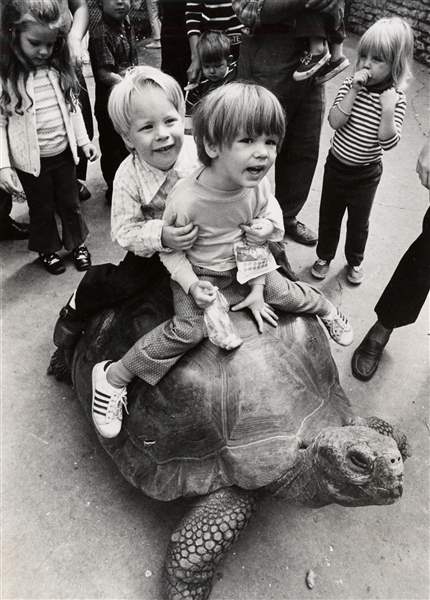

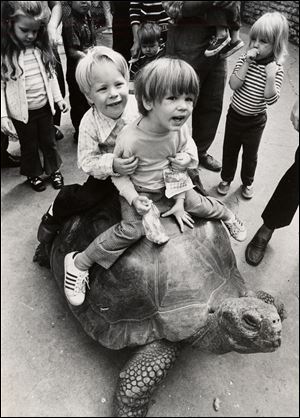

A pair of brothers hang on while riding Galopy in September, 1972. Despite enormous popularity among area children, the 60-year-old Galopy was given to the San Diego Zoo in 1983 after only 32 years at the Toledo Zoo. Such tortoises have a life expectancy of more than 150 years.

THE BLADE

Buy This Image

Frank ‘Curly’ Skeldon, feeding a penguin in 1949, became director of the zoo in 1926. Mr. Skeldon, a Blade business reporter and editor, received a token salary of $1 a month

It wasn’t uncommon for Frank “Curly” Skeldon’s phone in The Blade newsroom to ring with news of a building that was being torn down. Callers knew he could use the bricks and stone to help build Toledo’s fledgling zoo in Walbridge Park.

Even though he was a business reporter and eventually business editor of the newspaper, Mr. Skeldon’s passion was for the zoo growing in his South Toledo neighborhood.

And the savvy journalist used Blade time and resources to secure the rubbish that would help cement the infrastructure of the zoo, by filling in the Anthony Wayne Trail with stones and building the arch over the amphitheater with boulders.

Mr. Skeldon lived on Shadowlawn Drive with his wife and eight children, a stone’s throw from Walbridge Park where the zoo would emerge and prosper with his help and the support of The Blade.

The marriage between the Toledo Zoo and The Blade dates to the early days of the 104-year-old city institution, with Curly Skeldon the first, but not the last Blade employee, to champion the efforts of the zoo and help nurture it into one of the city’s jewels.

Seymour Rothman, who retired from The Blade in 1991 after 53 years as a writer and columnist, said The Blade and Mr. Skeldon truly took the zoo under their wings. He said Mr. Skeldon “practically owned the zoo” and “personally took possession of it.”

“The Blade has done what a newspaper is supposed to do,” Mr. Rothman said. “It has always supported the zoo.”

Out of love for the zoo, Mr. Skeldon offered to work there without pay. But a token salary of $1 per month qualified him as a staff member.

During the Skeldon family’s long-standing affiliation with the zoo, his wife often took care of baby lions and tigers in their home.

In 1900, the Hillebrand brothers from South Toledo put a woodchuck -- an overgrown rodent that looked like a small bear -- in a makeshift cage in the park along the Maumee River. People came out to see the furry animal, and by the end of that year, the woodchuck was among 39 animals, including baby bears, alligators, a golden eagle, and red foxes, on display at the zoo.

Amber prepares to gulp down a large jug of milk from zookeeper Dan Danford in June, 1955. The elephant was donated as a baby to the zoo by The Blade as a symbol for a school safety contest. The name, chosen in a citywide contest, stood for the amber caution signal on traffic lights.

Depression-era programs fueled building boom

During Mr. Skeldon’s affiliation with the zoo, which stretched from 1906 through the Great Depression of the 1930s, and until his death in 1948, the zoo reaped the rewards of federal relief programs, including the Works Progress Administration, which led to upgrades and new structures.

Five colonial-style buildings still used today were constructed during Mr. Skeldon’s tenure as director from 1926 until 1948.

“During the Depression, the zoo was really built,” said John Grigsby, a Blade reporter and editor from 1936 until 1989. “Frank was responsible for a lot of that.

“He was prone to grab his hat and coat and run off when he heard about bricks and stone that were made available. He would make sure the zoo got them and see that they got transported to the zoo.”

A renovation of the Primate House was under way as the WPA projects began. That building was rededicated on Sept. 15, 1934, the day of the Reptile House grand opening.

The ornate wood-and-stone WPA buildings changed the look of the zoo. Every May or June from 1936 through 1939, the zoo celebrated the opening of a structure. The Garden Club Building was doubled in size and renamed the Garden Center.

The Amphitheater, Indoor Theater, and Museum, though all connected, were opened separately. The Amphitheater opened in the summer of 1936, followed by the Indoor Theater that October. The Museum opened in May, 1938.

The Aviary opened in May, 1937. The zoo held a dedication ceremony in June, 1937, for the new buildings, though the Aquarium was under construction and would not open until June, 1939.

Other Depression-era projects included new exhibit cases, new visitor entrances, the demolition and reconstruction of the greenhouses and conservatory, and less obvious improvements -- new steam lines on the property and, from the city pumping station a mile away on Broadway, an extension of water lines.

The zoo benefited from another WPA project -- to fill in the former Miami & Erie Canal along the zoo’s northwestern property line. Workers first pulled stones from the bottom and salvaged boulders used at the canal’s locks, and the materials were reused in zoo construction.

The filled-in canal became the base for a highway -- the Anthony Wayne Trail -- between downtown Toledo and Maumee.

A pair of brothers hang on while riding Galopy in September, 1972. Despite enormous popularity among area children, the 60-year-old Galopy was given to the San Diego Zoo in 1983 after only 32 years at the Toledo Zoo. Such tortoises have a life expectancy of more than 150 years.

Another Blade figure continued a tradition

After Mr. Skeldon’s death, The Blade came through again for the zoo, as longtime outdoors editor Lou Klewer became director in 1950 for the same $1-a-month token salary as his predecessor.

The editor, who was a world traveler, agreed to run the zoo because of his love for animals, Toledo, and the zoo itself, wrote Ted Ligibel, author of The Toledo Zoo’s First 100 Years: A Century of Adventure.

In the early 1950s, The Blade donated an elephant to the zoo as a symbol for a school safety contest. The name Amber, which was chosen in a citywide contest, meant caution, like the amber caution signal on traffic signals.

Initially, Mr. Klewer agreed to lead the zoo for one year, but his tenure extended to three years before The Blade reminded trustees that it was unfair to ask him to continue leading the quickly growing zoo in addition to his newspaper work.

Upon Mr. Klewer’s resignation as zoo director in 1953, zoo board President Martin Janis said, “The highest kind of praise is due Lou Klewer. The enormous amount of work he has done for the zoo is best shown by the dozens of new species and the vital young stock we have obtained through his excellent ‘horse-trading,’ the beauty of the gardens, and the cleanliness of the whole park.”

But another Blade-affiliated Toledoan with deep ties to the zoo was ready to step in and lead the zoo into its modern era.

Skeldon’s son became facility’s 1st paid director

Frank Skeldon’s son, Philip C. Skeldon, who had been involved with the zoo his whole life, became the first paid director in a time when the demands of leading the expanding facility meant a full-time commitment.

In 1953, Phil Skeldon took charge of the zoo as a labor of love.

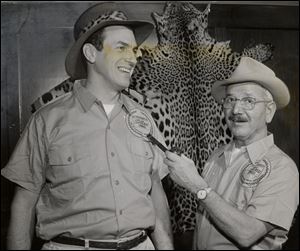

‘Jungle Larry’ Tetzlaff, left, and Blade outdoors editor Lou Klewer promote The Blade-Toledo Zoo safari to South America in 1960, which was undertaken to mark the newspaper’s 125th anniversary. Mr. Tetzlaff, an animal expert, led the safari.

When he was 8 years old, his first job was leading ponies around the pony ring. He later worked as a keeper and business manager, and then, its director. He helped the zoo acquire its first gorilla, and began breeding gorillas and orangutans.

During the second Skeldon tenure, a sea lion, penguins, otters, and beavers arrived at the zoo — helping lift the critter count to 2,256.

One of the zoo’s treasures during that era included Galopy, a tortoise and ancient Galapagos Island native which dwelled in one of the zoo’s most beloved places, Wonder Valley.

Despite enormous popularity among generations of Toledo area children, many of whom got to ride on the tortoise’s back, Galopy was given to the San Diego Zoo in 1983 after only 32 years at the Toledo Zoo.

Zoo officials, at the time, said the tortoise was sent to San Diego to benefit the animal and the breed. The California zoo had 27 other tortoises in 1983.

When he left Toledo, Galopy was about 60 years old. Galapagos Island tortoises have a 300-year life expectancy.

Safari in 1960 netted nearly 1,000 specimens

To mark The Blade’s 125th anniversary in 1960, Mr. Klewer took part in The Blade-Toledo Zoo safari to British Guiana and the Amazon River area in Brazil and wrote about the capture of an arapaima — the world’s largest freshwater fish.

The month-long journey, which netted nearly 1,000 specimens, including reptiles, mammals, birds, fish, and exotic flowers, also was made by, among others, Phil Skeldon and Dan Danford, the zoo’s curator of mammals.

The animals included an armadillo, rattlesnakes, anaconda constrictors, boas, iguana lizards, anteaters, a two-toed sloth, monkeys, great horned owl, king vulture, macaws, parrots, and about 200 tropical fish.

Upon their return on April 17, 1960, the safari members and the animals were greeted at Toledo Express Airport by about 1,000 people. Hundreds more lined the 22-mile route from the airport to the zoo, many along what was then known as Chicago Pike (now Airport Highway), to watch the caravan of vehicles carrying the animals pass.

The zoo’s museum also benefited from the safari. Brought back for display were a collection of insects, Indian baskets, beaded aprons, cassava implements, maps and books on British Guiana, and other items.

Mr. Janis, who served as board president until 1962 and was on the board from 1947 to 1985, said the expedition, made possible by the newspaper, “marks a significant step forward.”

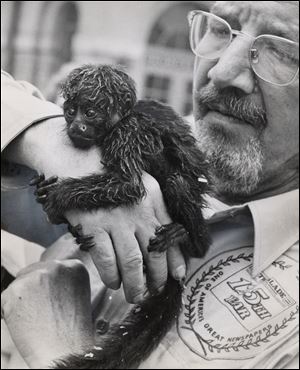

Mr. Klewer, a former zoo director, shows off a monkey after safari members returned to the Toledo Zoo.

1980s marked period of change for the zoo

After Phil Skeldon’s retirement in 1980, William Dennler became executive director and continues to lead the zoo today. He is paid $150,000 a year, and his total compensation is $173,950.

In 1982, the zoo changed hands. The city of Toledo transferred ownership during a financial crisis to the Toledo Zoological Society.

Over the years, a series of Lucas County tax levies to fund the zoo gained voter approval. The zoo last year received about $11.4 million from two property tax levies -- one for operating expenses and the other for capital improvements.

The most recent capital improvements levy was a 1-mill, 10-year measure approved in November, 1995. County and zoo officials miscalculated the amount 1 mill would raise, and the county has collected based on 0.92-mill that brings in $5.3 annually.

That capital levy has paid, in part, for the zoo’s expansion across the Trail with new exhibits featuring polar bears, wolves, and an African exhibit, along with a new entrance, parking lot, gift shop, and construction of a footbridge over the Trail.

The 1995 tax replaced a 0.5-mill capital improvement levy approved in 1990. The 1990 levy paid for such improvements as the Kingdom of the Apes exhibit and exhibits spotlighting Siberian tigers, Asian sloth bears, and African wild dogs.

The zoo first sought a capital improvements levy in 1980, when the city of Toledo wanted to reduce its annual contributions. A replacement 0.5-mill levy was approved in 1985 and funded the African Savanna project, which included the Hippoquarium.

In 1988, The Blade provided financial support to bring pandas from China to the zoo.

In 2000, the zoo’s animal count increased to 4,000, including 163 birds, 2,869 fish and invertebrates, 451 reptiles, and 163 mammals.

Yearly attendance surpassed 1 million a handful of times in the past two decades, the last time in 2004, driven in large part by the zoo’s popular annual holiday light display.

Begun in 1986 with a mere 50,000 lights, the display attracted 71,000 visitors.

Last season, Lights Before Christmas featured more than 1 million lights, over 200 lighted images of animals, ice-carving demonstrations, strolling carolers, and holiday treats. It attracted more than double the initial attendance.

In 2000, Block Communications Inc., the newspaper’s parent company, pledged $100,000 to the zoo in honor of BCI’s and the zoo’s 100th anniversaries.

The donation was used to sponsor the zoo’s entrance plaza, which was renamed Blade Plaza.

"Not only have we covered the news of the zoo for the past century, but also, we have made many contributions to the zoo,” said William Block, Jr., president of Block Communications in 2000.

Blade staff writers Mike Bartell, Tom Henry, and Mark Zaborney contributed to this report.

Contact Steve Eder at: seder@theblade.comor 419-724-6728.