Clash of philosophies, loss of animals triggered turmoil

Bear’s death marked turning point for veterinarian

3/13/2005

Tim Reichard, outside the Toledo Zoo’s Broadway entrance, was dismissed after more than 22 years as its veterinarian.

The Blade/Madalyn Ruggiero

Buy This Image

Tim Reichard, outside the Toledo Zoo’s Broadway entrance, was dismissed after more than 22 years as its veterinarian.

The concrete water bowl was shoved aside. In its place was a hole, scratched into the concrete, the last efforts of a dying bear trying to find water.

Diane Dawson fell apart when she saw it. She had cared for this sloth bear for months as its keeper. And now everything she feared, the very thing she tried desperately to prevent, had happened.

"It was awful. I cannot tell you what an awful experience that was. I loved her. She was a wonderful bear," Ms. Dawson said from her St. Louis home last week.

"We killed that bear."

It's an emotional milestone that raised the sense of urgency in the veterinarian, at the very moment the zoo's power structure was about to subtly shift in a way that would distance him from other middle managers and ultimately contribute to his estrangement from zoo executives. What followed was the slow but steady downfall of a man trapped on one side by management changes within the zoo, and on the other, by his own passion to protect and care for animals.

Dr. Reichard was fired by the zoo Feb. 28 after more than 22 years as its veterinarian. Zoo Executive Director William Dennler said the vet was dismissed because of "concerns over Dr. Reichard's administrative and management skills that we had worked with him to address over the last several years." Dr. Reichard maintains he was fired because he spoke frankly to inspectors from the U.S. Department of Agriculture in February, 2004, about animal deaths and animal care issues at the zoo.

READ MORE: Crisis at the Zoo

READ MORE: Blade played an integral role in the zoo's history

AT THE HELM TODAY:

After the inspection, top zoo officials were asked to correct 10 problem areas. Within the comments, the administrators were told: "The attending veterinarian has not been given the appropriate authority to ensure all aspects of adequate veterinary care."

On Friday, Tina Skeldon Wozniak, president of the Lucas County commissioners, announced the formation of an investigative committee to look into problems at the zoo.

Ms. Wozniak, the granddaughter of Frank 'Curly' Skeldon, former Blade business editor and first director of the Toledo Zoo, said, "The Toledo Zoo is too important ... to allow these questions to continue."

Also on Friday, zoo board President Stephen Staelin said he would convene a special meeting of the board to hear Dr. Reichard's plea to be reinstated.

Dr. Reichard was out of town when a sloth bear was mistakenly deprived of sustenance and died in 2000.

Reichard wasn't told of action fatal to bear

The death of the sloth bear was a nightmare moment for everyone at the Toledo Zoo. As the story of what happened unfolded, it was clear that poor communication and hubris had conspired in a tragic decision to isolate a bear, believed to be pregnant, without food or water.

There is an irony to the role the bear's death came to play in Dr. Reichard's future. It is this: Dr. Reichard was out of town when the bear was put into the den. He was not told the action had been taken. He never was informed of the keeper's pleas to give the bear food and water. And when he returned from a research trip, curators did not tell him that they had denned the bear.

Denning the bear without food and water was the decision of Tim French, large mammal curator. To all appearances, Mr. French failed to tell his supervisors what he was doing. But he did tell his staff, and Ms. Dawson tried to talk him out of it.

"He totally didn't listen to me," Ms. Dawson said.

Wynona Shellebarger, the zoo's other veterinarian, failed to take up Ms. Dawson's case, although she attended the meeting at which denning was discussed, Ms. Dawson said.

The daily notes Ms. Dawson filed in her keeper record, each one an accounting of her worries about the bear, brought no attention from anyone. Finally, her emotional distress was so great that she asked to be transferred to another part of the zoo.

She was working in primates when she learned her bear had died.

"Dr. Tim [Reichard] just felt so bad that it had happened. He just felt very responsible because I could not reach anyone. I could not reach anybody. He just felt so bad there was such a breakdown in the system and that I felt so much pressure," Ms. Dawson said.

Mr. French was forced to resign after the bear's death. But Dr. Reichard did not escape blame. As the chief veterinarian, he was deemed responsible for the veterinary staff's failure to intervene on behalf of the animal.

In Dr. Reichard's evaluation at the end of 2000, his supervisor -- then-Assistant Director Doug Porter -- wrote in three separate entries that the death of the sloth bear had undermined his confidence in the chief veterinarian.

Under the heading, "dependability," Mr. Porter wrote: "Normally very dependable, but my confidence was somewhat shaken by the death of the female sloth bear and the breakdown in communication it revealed."

Communication.

It was a word that would haunt the veterinarian until his last day at the zoo.

Management changes altered zoo landscape

By many accounts, if Dr. Reichard had a failing, it was that he overcommunicated. He flooded supervisors with memos and suggestions. He was a fountain of plans, new approaches, and ideas, all set down in writing and distributed up and down the line.

But with the sloth bear's death, by his own account, he seems to have picked up his pace.

"That's when I proposed we have these fact sheets when new animals came in, drafted for animal care. I was very vocal. I was very intent. If we had more stuff in place, the guidelines, this wouldn't have happened," Dr. Reichard said.

The death of a giraffe six months after the sloth bear's death didn't do much to ease his growing intensity. The giraffe died of tetanus after it was gored by an antelope-like animal called a kudu.

His blossoming urgency played into a weakness highlighted in Dr. Reichard's personnel file. The veterinarian had a tendency to be too insistent, sometimes inflexible, Mr. Porter wrote. Dr. Reichard was cautioned to work on his relationship with other managers. But while these things were noted, they didn't seem to set off any alarms in the reviews of a man who in every other way exceeded expectations.

Yet the notes were harbingers of what was to come.

When 2002 began, zoo organization was in transition. Mr. Porter left to take a post in Albany, Ga., and the zoo was bringing on a new No. 2 man in the Toledo Zoo management scheme.

He was Robert Harden, a veteran executive with experience in business, budgets, and employee relations -- all the heavy lifting the zoo would need. He had spent 14 years as executive director of the National Funeral Directors Association. Before that, he directed the New Jersey Bankers Association.

The fact that the zoo's new chief operating officer had no animal-care experience wasn't a problem, said William Dennler, the zoo's executive director. And it's not unheard of in zoo management.

"We were looking for anybody with a background that could run a zoo on a day-to-day basis. We didn't find anybody with an animal background who could do that. We chose Bob Harden because he was the best candidate," Mr. Dennler said last week.

But that left the institution without a general curator, a role Mr. Porter filled during his term as assistant director. To fill this significant gap, the zoo established the biological program committee.

The committee, not unlike such committees at other zoos, included almost anyone involved in animal care. Dr. Reichard and Dr. Shellebarger were active participants, as was the person in charge of animal enrichment and training and the zoo's research director. But, to Dr. Reichard's eyes, the biological program committee was clearly the curatorial staff's show. They were the voting members. He was not. They traded the duties of chairman every few months. He was not considered for the rotating chairman's post. And when a curator was chairman, he or she presented the group's issues to Mr. Dennler.

At the same time curators had been elevated to a new status, Dr. Reichard came to feel he'd been put in a less favorable position. He was now under the direct supervision of Mr. Harden, whose other duties involved the nuts-and-bolts of management such as finance and human resources.

Mr. Harden said his lack of animal experience wasn't a problem in supervising the veterinarian.

During his career, he said last week, he often had to oversee "departments in areas I know very little about,'' such as computer services. It's a matter of learning as you go, he said.

"The secret [is] having a strong line of communication with the people who report to you," Mr. Harden said.

Yet, after three years supervising the veterinary staff, Mr. Harden said last week that he did not know if federal law spells out responsibilities for the zoo's attending veterinarian. It does, in the Animal Welfare Act. And the responsibilities are broad.

USDA inspection fueled dissatisfaction with vet

By the end of 2003, there was little sign of any impending strife, although Dr. Reichard said he already was fighting a steady diminution of his authority caused by the new management structure at the zoo.

The veterinarian finished the year with one of the best performance reviews he had ever received. Mr. Harden wrote in Dr. Reichard's yearly performance review that the veterinarian maintained "the highest quality of work!" He also remarked: "Tim is well-respected throughout the zoo." The administrator went on to praise the veterinarian's technical skills, the amount of work he did, and his dependability. The issue of getting along with others still lingered, but again, there's no red flag: "Would like to see Tim focus more on people skills in department and with curators." And further: "Tim is strong in his beliefs, and sometimes needs to temper that once a final decision is made."

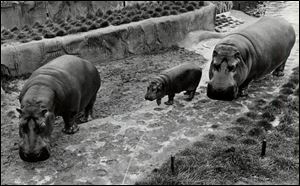

Then a USDA inspection team went to the zoo and issued its February, 2004, report. In addition to addressing the need to grant the veterinarian appropriate authority, it cited the 2003 death of a 48-year-old hippopotamus -- Cupid, known to school-aged children across Toledo, who was found near death in his enclosure, his blood splashed on the walls. Dr. Reichard said he thought a keeper had inadvertently shut a powered concrete and steel gate, not knowing that Cupid had fallen, and the gate had crushed the animal's head.

The investigation process stunned the zoo staff. USDA inspectors refused to talk to some keepers and sought out others, said Randi Meyerson, mammal curator. The zoo had just been inspected in October, 2003 without a hitch. Now investigators were aggressively questioning certain individuals but said they were too busy to talk to others.

Cupid, left, was found dead in 2003 in his enclosure, his blood splashed on the walls. Dr. Reichard said he thought a keeper had inadvertently shut a powered gate, not knowing that Cupid had fallen, and the gate had crushed the animal's head.

Dr. Reichard became the focus of dissatisfaction by zoo officials with the inspection.

"The vet that's in charge is to help the zoo meet [Animal Welfare Act] standards," said R. Andrew Odum, the curator in the herpetology department. "They're also responsible to represent the zoo to the USDA, like a lawyer.

"We felt it was Tim's responsibility to make sure the zoo was properly represented and make sure they had all the information, to make sure that the truth comes out," Mr. Odum said.

When investigators wouldn't talk to some people, the curators thought the veterinarian was at fault.

The zoo responded by launching an internal investigation of the hippo's death and the death of the giraffe gored in 2001. But this did nothing to close the gulf growing between the curatorial staff and Dr. Reichard. If anything, it widened it.

At least one of the conclusions of the investigation focused on an issue that would become a major theme of complaints about the veterinarian -- his close association with keepers.

In the case of Cupid's death, the internal review committee found "inappropriate" what they called "a closed investigation undertaken by the senior veterinarian" and a keeper.

The way Dr. Reichard tells it, he was chatting with a keeper the night of the hippo's death. The keeper suggested that the hippo might have had its head jammed into a tight space by the closing of a heavy powered door. Initially, the veterinarian said he dismissed the speculation, noting that if the hippo had been trapped by the door ever since it was closed at about 10 a.m., there should have been feces around the animal. There was none.

But in later discussions, Dr. Reichard learned the animal had been outside earlier in the morning. It was possible the animal had eliminated adequately before it was trapped by the door. When Dr. Reichard saw the hippo's broken neck and the severe damage to the surrounding tissue, he theorized that, indeed, that's what happened.

Mr. Odum, who chaired the internal review committee, said the problem in the hippo's death was the keeper who "failed to tell the curator, which is his direct supervisor, of a potential incident or accident. Instead, he later got with Dr. Reichard the same evening and told him."

The internal review acknowledged it was impossible to tell with certainty what killed the hippo but suggested the blame for that uncertainty fell on Dr. Reichard and the keeper who talked to him, for not reporting their speculations immediately to the mammal curator, biological program committee, and the executive director. Under the Animal Welfare Act, it is the veterinarian who has responsibility for necropsies.

"If a complete investigation was initiated immediately after the animal was euthanized, many of the unanswered questions would have been resolved," the report states.

The notion that Dr. Reichard talked too much to keepers, thereby "empowering" them to bypass their immediate supervisors and undermining curators' authority, crops up over and over again through the year.

"I think he empowered the keepers to go around the supervisors and go to him when they didn't get the answer that they liked," said Beth Stark, curator of behavioral husbandry and research, echoing comments of the other curators.

Dr. Reichard saw the issue from a completely different perspective. First, he said, he always told the keepers to go to their curators with whatever they told him. Second, he said he relied on keeper observations of animals in order to make sure the animals stayed healthy -- one of his legal responsibilities. After all, they were the zoo employees closest to the animals.

Instead, Dr. Reichard worried that keepers were subject to discipline for talking to him, something he said he'd seen occur.

"People don't feel free to be open. Discussions don't happen. [There is] control of information, control of communications, control of decision making," he said.

Frustration, criticism mounted before firing

As last year wore on, Dr. Reichard grew increasingly frustrated.

"I'm trying to run the zoo. I was told that in a reprimand," he said.

An attempt to participate in a meeting to discuss a new gate in the mammal department seemed to twist and turn in a bewildering number of phone calls, voice mails, and discussions about who the vet was allowed to speak to and finally ended up in the second warning zoo administrators issued to Dr. Reichard.

In a follow-up letter to that warning, a zoo consultant scolds Dr. Reichard: "You let a faulty door go uncorrected for several months, and then waited until Ms. Meyerson was gone to address it after you were told to work through her. Then, in order to cover your tracks, you intimidated and harassed zoo employees."

As Dr. Reichard reels in this confusion, some of the people around him say they see a change in his behavior.

Peter Tolson is director of conservation and research at the Toledo Zoo. Because he's not involved in day-to-day animal care, he's a step removed from the disagreements that arose between curators and the veterinarian.

"I'm kind of like a bystander who's looking in with a lot of trepidation on what's going on around me, feeling very bad for everyone involved," Mr. Tolson said. And what he saw was a change in Dr. Reichard's demeanor.

"It started, actually, a couple of years ago. It wasn't for the better," Mr. Tolson said. "It seemed in the past that Tim relied on gentle persuasion to bring people over to his way of thinking.

"In recent years, particularly in the past year, Tim has been more of a disruptive influence at the zoo," Mr. Tolson said. "It saddened me greatly to see this. His style, particularly regarding Wynona [Dr. Shellebarger], was quite confrontational in my opinion.

"I don't want to give the impression that I thought Tim was malicious, because I don't," Mr. Tolson said. "Tim, in his own mind, thought he was doing what was right."

Today, many are upset about what this controversy is costing the zoo, what the arguments are doing to employee morale, and what will be the final result.

"I'm really proud to work for the zoo, and I'm proud for what the zoo stands for," said Ms. Stark, curator of behavioral husbandry and research. "I hope that we can soon move beyond this and get back to what we do best, which is being a great zoo. This has taken all of us away from working with the animals, which is really what we need to be doing."

Contact Jenni Laidman at: jenni@theblade.com or 419-724-6507.