'I'm not a monster': 10 years after killing his foster mother, Johnnie Jordan wants to explain

6/4/2006

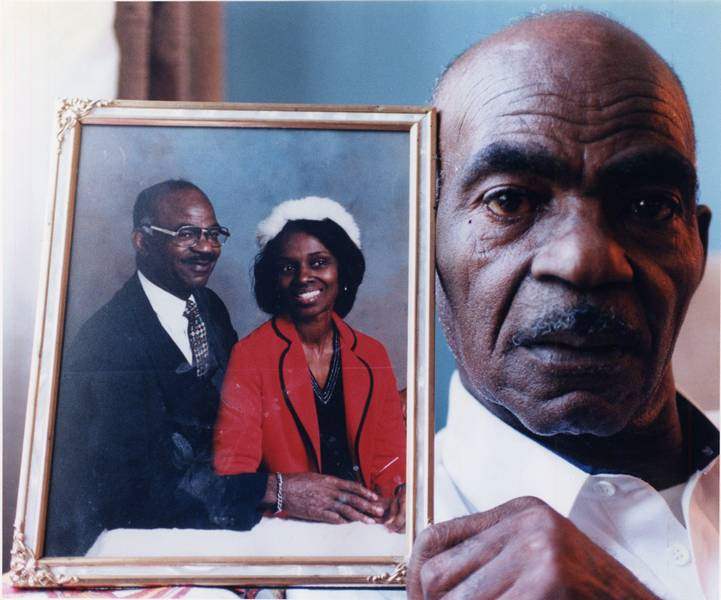

Charles Johnson in mid-1996 holds a photograph of himself and his wife, Jeanette Johnson, who was killed by Johnnie Jordan in January, 1996. Mr. Johnson died 11 months after her.

Johnnie Jordan isn't asking you to forget the woman he killed - a tiny, 62-year-old foster mother known for a kindness that was so simple and unassuming it seemed bizarre, even suspicious, to a kid who'd grown up in a home full of filth and stench, drugs, and abuse.

He isn't asking you to forgive him, either.

After all, he admits he picked up a hatchet, walked up to Jeanette Johnson, and then crushed her skull and hacked at her body. It was he who found the can of kerosene, dropped a lighted match, and walked away.

Still facing at least 26 years behind bars, Jordan understands too why some might want to forget about him.

But the least you can do, he pleads with a visitor, is listen.

"Time has passed. I think I deserve a chance to explain what happened that day." And even more insistently: "I'm not a monster."

Certainly, a lot has changed since 1996, when 15-year-old Johnnie Jordan sat with police, sipping a soda and confessing cold-blooded murder.

Now 26, he said the white-hot rage he felt the night he picked up the hatchet has evaporated.

These days he works in one of the jobs that requires the most trust - the commissary - at Toledo Correctional Institution.

"I have really seen him grow," Warden Khelleh Konteh said. "He came here as a kid."

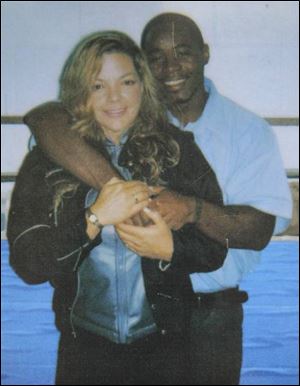

Johnnie Jordan embraces Pamela Smith, 46, in the Toledo Correctional Institution. They began corresponding in 2004. She calls him the love of her life and advocates his early release.

He's got a girlfriend too. She moved from California to be nearer to him.

Said 46-year-old Pamela Smith, "He's the love of my life."

Mrs. Johnson's murder on a bitter cold Jan. 29, 1996, was unforgivable. Jordan's childhood was shocking as well.

Jordan's few years with his parents were detailed in The Blade as his case unfolded and five years later in a book, written by Jennifer Toth: What Happened to Johnnie Jordan? The Story of a Child Turning Violent.

Instead of feeding their seven children, Marilyn and Johnny Jordan, Sr., bought dope. Instead of getting them to school, they'd vanish for days, leaving the children in a squalid house often with little, if any food, utilities, or furniture.

The children were sickly. Jordan said they begged and stole to eat.

Jordan still remembers stray animals in the house. No one bothered to clean up their mess.

Charles Johnson in mid-1996 holds a photograph of himself and his wife, Jeanette Johnson, who was killed by Johnnie Jordan in January, 1996. Mr. Johnson died 11 months after her.

Other kids sneered. Jordan didn't understand them at the time. Now he doesn't blame them.

"We didn't take baths and stuff like that. We'd smell like urine and kids picked on us," he said recently from prison, his spot-free state-issue uniform crisply ironed.

Lucas County Children Services periodically took the siblings away, splitting them among several foster homes and scheduling visitation at the Toledo office between Johnny and Marilyn Jordan and their children.

"The first couple of times my mother and father would come and see us, and say, 'We're trying to get you back home.' Then after a couple of months, we'd be waiting down there and they wouldn't show up," Jordan recalled. He shook his head. "That's sad on a kid."

The elder Jordan eventually went to prison for raping children; Marilyn, for allowing it. By then, several of the siblings were facing troubles of their own with the law. Johnnie kept running away. He punched a TARTA bus driver.

Johnnie asked foster parents to adopt him. They wouldn't. He wanted to be with his real parents. He couldn't.

By the time he was placed with Charles and Jeanette Johnson, an elderly couple in Spencer Township, in December, 1995, he'd reached his "boiling point," Jordan said.

Jordan liked the Johnsons - he was a pastor, she a homemaker. They'd had no children of their own, but the couple took in some of the county's toughest foster kids.

Mrs. Johnson was a great cook. Mr. Johnson played cards with the teen. They got him a suit - Johnnie's first - and he went with them to church.

Several weeks passed, but by the end of the first month of 1996, Johnnie was angry again. He'd heard that he'd soon be shuffled - again - to another foster home.

"I just had to explode," he said.

Mr. Johnson, he recalled, had gone to the store that afternoon. Around dinnertime, Mrs. Johnson was in the kitchen washing dishes, her back to Johnnie in the living room.

Inside a prison hearing room recently, Jordan leaned back on his chair, his palms resting on his thighs. He inhaled.

He'd felt caged that gray winter day, and now his mind filled with strange voices, Jordan recalled. They told him to kill.

"It was like a devil. You know how you see the cartoon characters, you know - the good one on this shoulder and the bad one on that shoulder?"

Twice he had walked toward Mrs. Johnson. Twice he'd retreated. Now she had her back turned to him, preparing to do dishes.

"At first I was doing battle with myself," he said. "You know: 'Just hit her on the side of the head,' and this side telling me, 'Don't do it.' It literally drained me. I didn't know what to do. I was confused."

For the third time, he walked toward Mrs. Johnson. This time, he smashed the hatchet into her head. The voices, he said, stopped.

Mrs. Johnson stumbled backward and turned. She briefly looked at him. Johnnie hit her again and again and again.

From prison, Jordan insisted he was only lashing out at a world that didn't want him.

He said he felt no particular malice toward Mrs. Johnson. "She was a nice lady."

It wasn't the murder so much that stunned Pamela Smith when she read What Happened to Johnnie Jordan. It was his hellish childhood.

The mother of two began corresponding with Jordan from her home in California. By the end of 2004, she'd moved to West Toledo, where she now runs a Web site, www.supportjohnnie.com, that advocates Jordan's early release.

"You know, a lot of people are critical of our relationship because he's an inmate and they say inmates tend to pimp women with their words; use them for whatever they can get," Ms. Smith said. "Johnnie is genuine; he's authentic."

The Johnnie she knows calls her house each night to check on her children and orders stuffed animals and flowers for her from catalogs. And he choked up when her children belted out "Happy Birthday" to him inside the prison's visiting room.

He's the Johnnie who helps her 13-year-old daughter with multiplication tables and makes bets with her 9-year-old son - loser buys a pop - over sports teams.

It took her a year to ask Jordan about the murder.

She sighs: "I can't fathom him doing something like that."

At the neatly trimmed Highland Memory Gardens near Waterville, Memorial Day draws loved ones of those buried there.

They bring plastic crosses and silk flowers and American flags.

In 1982, Jeanette and Charles Johnson made their way to the cemetery to purchase a $550 plot. Mr. Johnson signed his name in his crooked scrawl; she followed with dainty cursive.

These days, the simple bronze marker over their graves bears no telltale signs of recent visitors. Grass creeps over the words, "Together Forever."

Most likely an oversight, no one has affixed the tiny plate to let a visitor know that Mr. Johnson also died in 1996 - 11 months after his wife's murder.

Mrs. Johnson's relatives could not be reached for comment.

Toledo attorney Alan Konop, who filed a lawsuit for Mr. Johnson against Lucas County Children Services after his wife's death, remembered Mr. Johnson as "one of the kindest people I ever met."

Children Services, the suit alleged, placed Jordan with the Johnsons without warning them of the boy's violent past. The suit wasn't about money, Mr. Johnson said. It was to protect foster parents.

After the murder, the agency hired a new director, the county agreed to settle the Johnson lawsuit for $490,000, and a state law was passed that gives foster parents better access to information about violent children they take in.

Mr. Johnson told reporters that he and his wife still would have taken in Johnnie, even with his past.

"He said he just wouldn't have left his wife alone" with Jordan, Mr. Konop said.

Former Lucas County Detective Ernie Lamb is still haunted by the case.

As unsettling to him as Johnnie's confession is the fact that Johnnie seemed like a decent kid whose past made him a murderer. It's easier, the detective said, to lock up "a bad seed," a remorseless criminal from an otherwise good upbringing.

But Jordan, he said, is too dangerous to be released anytime soon.

"I feel sorry about the way he was raised, but prison doesn't change a person's mind," he said.

Judge James Ray, the juvenile court judge who certified Jordan to stand trial as an adult, said he has seen countless children irreparably damaged when their families discard them.

But with a murder like that of Mrs. Johnson, the judge said, community safety outweighs any mitigating circumstances.

"I'm of the belief that there are some crimes where - no matter how much a person changes, gets religion, or whatever - the penalty needs to be carried out."

For his part, Jordan said he's trying to respect those opinions while remaining optimistic that he may gain early release. Given a life sentence by a three-judge panel, his first parole hearing isn't until 2032.

"I'm very spiritual and I believe that anything can happen," he said. "It's not looking too good right now, but you never know what can happen in the next couple years, the next 10 years. Laws change. People change."

Contact Robin Erb at: robinerb@theblade.com or 419-724-6133.