The week that shook nuke power

3/29/2009

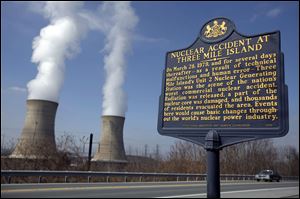

A historic marker stands near the Three Mile Island Unit 2 reactor, site of the March 28, 1979, nuclear accident, as steam pours from the cooling towers of the TMI Unit 1 plant on a recent day.

Thirty years ago this weekend, America was mired in its darkest chapter of civilian-operated nuclear power - a harrowing, five-day series of events at the Three Mile Island Unit 2 reactor in eastern Pennsylvania that began on March 28, 1979.

Though nobody died at the scene - unlike the explosion of Ukraine's Chernobyl reactor seven years later - half of Three Mile Island Unit 2's reactor core melted, a fact that wasn't discovered for nearly a decade.

The amount of radiation that was released and its resulting impact on public health has been debated for years.

But historians look back at Three Mile Island in a broader sense. Most agree it was a wake-up call for a country that had put almost unwavering faith in the nuclear age, hoping it would provide more energy security after Americans had learned how vulnerable they were following the 1973 OPEC oil embargo.

History now repeats itself, with the nuclear industry marketing itself today as a panacea for anything from climate change to unstable electricity prices while imports of foreign oil remain high.

So what lessons were learned from Three Mile Island?

That was the focus of a 2 1/2-hour hearing in Washington that the U.S. Senate's subcommittee on clean air and nuclear safety held last Tuesday.

Three Mile Island led to major safety reforms, from detailed evacuation plans to industry-led auditing of safety systems. But the resounding theme was that the biggest lesson - guarding against complacency - was forgotten by both the industry and its government watchdog, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, officials said.

NRC Commissioner Peter Lyons said the "recent Davis-Besse incident shows that we must remain ever-vigilant, that the [Three Mile

Island] lessons must never be forgotten."

He and others who testified drew countless parallels between Three Mile Island's half-core meltdown and the near-rupture of Davis-Besse's old reactor head in 2002, the latter of which also would have allowed radioactive steam to form if it had burst. Federal investigators found it had been neglected for years.

Those testifying included past and current NRC commissioners; former NRC nuclear reactor regulation director Harold Denton, who was former President Jimmy Carter's right-hand man at Three Mile Island, and Marvin S. Fertel, the Nuclear Energy Institute's president and chief executive officer.

Both incidents shook public confidence in nuclear power, they agreed.

U.S. Sen. George Voinovich (R., Ohio), a staunch nuclear power advocate who lives 30 miles east of Davis-Besse, said he prodded the NRC into doing its job, both as a member of that Senate subcommittee and in private meetings in his office with agency officials, including the last two NRC chairmen.

The Senate subcommittee has held 20 hearings about Davis-Besse over the past eight years, he said.

"We took the NRC to task, as it was initially reluctant to address the issue of safety culture," Mr. Voinovich said, referring to a type of broad and largely undefined workplace exams that began with Chernobyl and have been used at other industrial sites, from NASA space programs to BP refineries.

Such a probe consumed the second year of Davis-Besse's record two-year outage. The NRC said at the time it needed proof that FirstEnergy Corp. had convinced workers to be more forthcoming about safety issues before allowing it to resume operation, which the agency did in 2004.

Mr. Fertel said Davis-Besse "was a failure not only on FirstEnergy's part, but also the NRC and INPO's part." The latter was a reference to the Atlanta-based Institute for Nuclear Power Operations, a group of self-auditors the industry put together in response to Three Mile Island.

Three Mile Island remains the site of America's worst nuclear accident with a commercial-sized reactor. Some less-publicized ones involved experimental reactors.

The Three Mile accident occurred about 10 miles southeast of Harrisburg, Pa., at a reactor that had been online for only 90 days.

The nuclear industry and the NRC were "unfortunately humbled" by the accident, Mr. Voinovich said.

The NRC continues to keep a mock-up of Davis-Besse's old reactor head in the lobby of its headquarters to help guard against complacency, Mr. Lyons said.

Akron-based FirstEnergy, which owns Davis-Besse, the Perry nuclear plant east of Cleveland, and the twin-reactor Beaver Valley complex west of Pittsburgh, inherited Three Mile Island Unit 2 as a result of a 2001 utility merger. Three Mile Island Unit 2 and its predecessor, Three Mile Island Unit 1, were operated by Metropolitan Edison at the time of the accident.

Contact Tom Henry at:

thenry@theblade.com

or 419-724-6079.