Toledo hydrant inspections come under scrutiny

7/19/2009

After deftly twisting off the cap on the front of a fire hydrant on Woodruff Avenue near downtown, hydrant inspector Robert Townsend applied his wrench to the huge nut on the top of the hydrant that opens a valve about 5 feet below.

"This will be one that I write up," Mr. Townsend said, as he muscled the reluctant valve open, sending a torrent of rusty water gushing into the street.

As one of four workers traveling the city daily with a van load of wrenches, grease, paint, pumps, chains, and hoses, Mr. Townsend's job is to make sure the hydrants work when firefighters turn to them to douse blazes.

In the month since fire destroyed a stately home in Toledo's historic Westmoreland neighborhood, attention has focused on the city's system of nearly 10,000 hydrants.

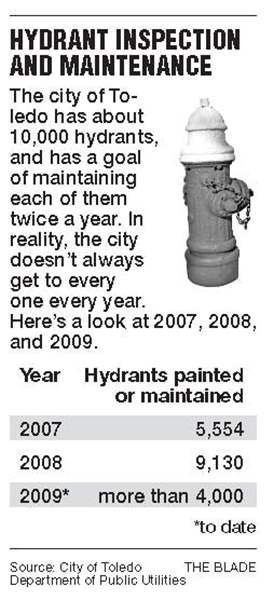

A report issued two weeks ago by a three-person committee appointed by Mayor Carty Finkbeiner to investigate the fire said that the city has a four-person team assigned to check each of the nearly 10,000 hydrants twice a year.

But the city's Department of Public Utilities is unable to produce records that clearly show which hydrants have been tested. And its activity reports show that the city is not inspecting every hydrant even once a year.

According to summary activity reports provided by the Division of Water Distribution, 5,554 hydrants were maintained in 2007 and 9,130 in 2008. So far in 2009, more than 4,000 hydrants have been maintained, according to David Welch, commissioner of field operations in the utilities department.

Colleen Kilbert, president of the Westmoreland Neighborhood Association, said Tom Kroma, the director of Public Utilities, and Utilities Commissioner Donald Moline have not been able to prove to neighborhood residents that hydrants are tested as often as they claim.

"I've been really disappointed in Tom Kroma's and Don Moline's ability to really state definitively what the standard procedure is for testing the flow, testing the hydrants. They hem and haw around it," Ms. Kilbert said.

"There's no records to show it. It's a good idea, but they really can't back it up that it's been done," Ms. Kilbert said.

Nor can Fire Chief Mike Wolever cite documents that prove the hydrants are being inspected twice a year. But he said he knows they are inspected because of how well they operate, especially in winter when frozen hydrants can spell disaster.

"There is a substantial program by DPU to maintain the hydrants," Chief Wolever said. "If they don't do what they say they're doing, we're going to have frozen hydrants all over the City of Toledo."

Instead, he said it's a rarity for firefighters to encounter a broken or frozen hydrant.

"We would raise holy hell if we weren't getting the water we needed from the hydrants," Chief Wolever said. "We're going to two to three fires a day." In fact, he said, the hydrants are in "excellent condition."

Since the June 9 fire at the home of Herman and Barbie Harrison, at 1945 Mount Vernon, Chief Wolever hasn't complained about the low water volume firefighters encountered from a hydrant in front of the home.

Instead, he's tried repeatedly to explain to residents and the media how low water volume didn't hamper firefighters' efforts to fight the blaze.

Firefighters complained about low water volume while fighting the fire, and when they went to a second hydrant they found it was broken, with water gushing out of its base. It turned out the first hydrant was on a low-volume, 4-inch main, yet firefighters didn't "lay into" a hydrant on a higher-volume, 6-inch main about two blocks away until more than 90 minutes after arriving at the fire.

By then, the Harrison home was a complete loss.

The low-volume hydrant was capable of only 150 gallons of water per minute, compared with the more than 1,000 gallons per minute that would pour out of a 6-inch or 8-inch water main now standard in residential development.

Chief Wolever initially said he didn't know if laying into a 6-inch main would have made a difference in the Harrison fire.

After reviewing the testimony of those involved in fighting the fire, he concluded the fire was too advanced inside the house for more water volume to have made a difference.

Still, the Department of Public Utilities has moved ahead and replaced three of the 4-inch hydrants on Mount Vernon with hydrants on 6-inch mains.

A total of 8.75 miles of city streets scattered across Toledo are served by hydrants on 4-inch mains.

When it comes to maintaining hydrants and documenting their work, the city relies on basic tools and old-fashioned pen-and-paper reporting.

The city's water distribution division divides the city's fire hydrants into four zones centering on Detroit Avenue and Bancroft Street, with one inspector for each zone.

Those inspectors' jobs are to visit hydrants all day long and check for functionality, according to Terry Russeau, acting manager of water distribution.

He said each inspector may check 35 hydrants a day, but Mr. Townsend said he gets to about 16 or 17 hydrants a day.

The work involves removing the caps on the hydrant and opening the valve to let the water flow for a few minutes. The inspector then applies grease to the threads on all the caps. If the chains that tie the caps to the hydrant are missing, he replaces them.

If water has collected in the hydrant, that means there may be a leak, and the hydrant is pumped out and referred for repair or replacement.

Mr. Townsend said if he flags a hydrant, a foreman will check the hydrant and put in a work order if the hydrant needs repair or replacement. "It's a good system," he said.

Mr. Welch said the department averages 10 to 15 hydrants out of service. He said the department replaces 400 to 500 hydrants a year, at a cost of about $1,500 per hydrant.

He said the inability to get to every hydrant twice a year isn't the whole picture.

He said there are other things done with the hydrants, including flow testing, that isn't reported under maintenance or painting.

"It's a goal. We'd like to get to it. But I think we're doing a good job if you look at the number of hydrants out of service - 10 to 15 out of 10,000 hydrants," Mr. Welch said. "These guys are out there every day. We know where the issues are."

The inspectors keep track of the hydrants they've visited not by entering a record in a desktop or hand-held computer but on a looseleaf binder "book" that travels in the aging vans used by the four hydrant inspectors.

To figure out when a certain hydrant was inspected, a supervisor has to cross-check with a meticulous mileage log that the hydrant inspectors also maintain.

Only if a hydrant is repaired or replaced is it entered into a computerized reporting system.

The hydrant inspectors treat the "books" like Scripture. To lose the book would be to lose months' worth of records of hydrant inspections.

Mr. Russeau said the hydrant inspectors check mainly for frozen hydrants during the winter months, using steam equipment to thaw out the hydrant and drain water that may have crept up into the cylinder.

Yet another job involving hydrants is the test for water-flow volume and pressure. Mr. Russeau said that work is more time-consuming and is done usually when construction is planned.

The inspectors also are supposed to paint hydrants, but they can't do that at the same time that they're checking for flow and adding grease.

Before the Westmoreland fire, Mr. Townsend told The Blade, the emphasis was on painting the hydrants.

He said since the fire he's been told to focus less on painting and more on testing and maintaining the hydrants.

"I'd rather maintain them than paint them," said the city employee since 2002, who formerly worked in auto-parts factories that closed.

"I can make it look pretty. If it doesn't work, it doesn't help anybody," he said, saying he'd feel bad if firefighters were delayed by a frozen or broken hydrant in putting out a fire. "I sleep better if a fire breaks out in an area that I know they have a good hydrant. I look at it as protecting the public."

Mr. Welch denied that the hydrant inspectors have been told to shift from painting to maintaining hydrants.

"There is no memo, no e-mail, no phone calls, no nothing to change what we've been doing. They go out and maintain fire hydrants. If they're cracked, chipped, whatever, they paint them," Mr. Welch said.

Fire hydrant painting has been a priority for Mr. Finkbeiner since he first was elected in 1993. Shortly after taking office, he ordered city fire hydrants repainted green to better blend in with the landscape as part of his Toledo beautification program.

Firefighters complained about the change from bright yellow, which were easier to identify at fire scenes, and recently retired fire chiefs said the painting covered over color coding on the hydrants that identified for firefighters the low-flow 4-inch hydrants.

Continued reports of the hydrant painting have set the Finkbeiner administration on edge, with Mr. Kroma, the director of Public Utilities, recently telling The Blade: "To continue to go down that path and say we used to do that is inaccurate. To say that they were changed when Carty Finkbeiner came in is totally inaccurate and we're going to have to rebut it."

Who is supposed to inspect and maintain hydrants has been a matter of dispute over the years.

State law makes maintenance and testing of the fire hydrants a responsibility of the local top-ranking fire official - the fire chief in Toledo - in conjunction with the water department.

In 1997, Firefighters Local 92 filed a grievance claiming that inspecting hydrants should not be the firefighters' job.

Through their lawyer, Donato Iorio, they argued that they were being ordered to inspect hydrants by Mr. Finkbeiner because he was under pressure from the news media over the poor condition of fire hydrants.

The arbitrator, Harry Graham, agreed in an April 14, 1998, ruling that Mr. Finkbeiner had ordered firefighters to do work that was not in their union contract and said the hydrants should be inspected by members of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees Local 7 bargaining unit.

Former Fire Chief Mike Bell, now an independent candidate for mayor, insisted that firefighters used to check the hydrants through the Fire Prevention Bureau until that duty was transferred to the water department.

He said the fire department may have lost some familiarity with the water hydrant system when it was ordered by the arbitrator to stop testing hydrants.

Chief Wolever agreed that firefighters used to open hydrants to make sure water came out and that the caps screwed off, and that they don't do that anymore.

As a result, he said, there has been a loss of knowledge about the locations of hydrants among the newer firefighters.

But he said the responsibilities of the fire department have multiplied in recent years to include emergency medical response, knowledge about homeland security, and how to respond on hazardous materials situations and cave-ins.

"All they had to do back then was worry about water. Today, we have a lot of other things to worry about. We know the water department maintains this stuff. We know that [the hydrants] are working, and I'm comfortable with that," Chief Wolever said.

He said the changes that have been recommended in the aftermath of the Harrison fire, including adding information on computers in the fire trucks to ensure firefighters know what kind of water mains the hydrants are tied in to, are all for the good.

"I'm even more comfortable when we get the electronic retrieval system up and running," he said.

The chief said he complies with his responsibility under state law by meeting on a quarterly basis with the water department to discuss the maintenance of the hydrants.

Contact Tom Troy at:

tomtroy@theblade.com

or 419-724-6058.