Rise in tornadoes no certainty as Earth warms, scientists say

6/14/2010

Although climatologists are certain more violent weather events lie ahead, they are less sure that we'll have more tornadoes, like the EF-4 twister on June 5 that wrecked this Millbury home.

The Blade/Amy E. Voigt

Buy This Image

Although climatologists are certain more violent weather events lie ahead, they are less sure that we'll have more tornadoes, like the EF-4 twister on June 5 that wrecked this Millbury home.

You may have heard that thunderstorms, lightning, sleet, hail, damaging winds, and hurricanes will occur more frequently later this century if the Earth's climate continues to warm as rapidly as America's top climate scientists believe it is now.

But tornadoes? Not so fast.

"This science is in its infancy," explained Tony Del Genio, a climatologist at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York City.

Mr. Del Genio's words of caution may be noteworthy to those who follow climate research.

NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies is widely considered one of the U.S. government's most authoritative research facilities on the subject. Its director, James Hansen, was the first to testify before Congress about climate change in the 1980s and became a higher-profile figure after the New York Times published accounts claiming his work had been censored by the Bush administration.

Tornados' frequency, violence June 14, 2010" rel="storyimage1" title="Rise-in-tornadoes-no-certainty-as-Earth-warms-scientists-say-2.jpg"/>

Tornados' frequency, violence June 14, 2010" rel="storyimage1" title="Rise-in-tornadoes-no-certainty-as-Earth-warms-scientists-say-2.jpg"/>

<img src=http://www.toledoblade.com/assets/jpg/TO66067417.JPG> <b><font color=red>VIEW CHARTS:</b></font color=red> <a href="/assets/pdf/TO72549614.PDF" target="_blank "><b>Tornados' frequency, violence</b></a> June 14, 2010

Mr. Hansen now has a best-selling book, Storms of My Grandchildren: The Truth About the Coming Climate Catastrophe and Our Last Chance to Save Humanity.

He said in a YouTube interview on the book's Web site that a big gap exists between what scientists know about climate change and what the public believes.

"It may take some more examples from Mother Nature for people to sit up and notice," he said.

But while scientists are convinced the status quo will result in more violent weather years from now, tornadoes are "really beyond the edge of our understanding of things," according to Mr. Del Genio, the lead author of a 2007 report which NASA claims broke new ground by the way it connected more dots between anticipated climate change and storm intensity.

That report found there will be fewer soakers and gentle rain showers, and more of the most severe and dangerous storms.

Mr. Del Genio said he is hesitant about making predictions about tornadoes, because - bar none - they are nature's hardest weather event to predict.

That's especially true of the most dangerous and destructive types of twisters, those classified as EF-5 and EF-4 on what meteorologists refer to as the five-point Enhanced Fujita Scale.

Developed by T. Theodore Fujita of the University of Chicago, the Enhanced Fujita Scale was originally known as the Fujita Tornado Damage Scale. The two most violent types of tornadoes under that scale were classified as F-5s and F-4s.

The June 5 tornado that killed six northwest Ohio residents was an EF-4, the second-most destructive with winds of more than 165 miles per hour.

Tornadoes are hard to predict because they're essentially flukes of nature. Unlike hurricanes, they form spontaneously, are short-lived, and traverse a much smaller land mass by comparison.

Many atmospheric conditions need to converge at the right time for tornadoes to form.

They need hot, humid air near the ground with a cool air mass above them.

Among other things, they also need strong wind velocity at higher altitudes, known as wind shear, to get them spinning, Mr. Del Genio said.

Many of those ingredients likely will be in greater abundance as the Earth's climate warms over the next 50 to 100 years, he said.

"We're talking about something our children might see by the time they're old," Mr. Del Genio said.

He said a more frequent convergence of tornado-inducing atmospheric conditions doesn't necessarily correlate to more twisters, though.

All it does is improve the odds.

"Just because you have a favorable environment [for tornadoes to form] doesn't mean you'll have a storm," agreed Harold Brooks, a meteorologist who specializes in tornado research at the National Severe Storm Laboratory in Norman, Okla., operated by the federal government's National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The Great Lakes region is especially hard for long-range predictions because of the fickle relationship between its enormous bodies of water and the air masses hovering over them, Mr. Brooks said.

There are other variables too.

For starters, it's unclear how much wind shear will continue to be a factor.

It tends to be stronger in the winter, when the collision of warm and cold air masses forms the most powerful jet stream.

That's why most tornadoes form in late spring and the first part of summer, as opposed to the dog days of August, according to Mr. Brooks, who authored a 2003 NOAA report considered one of the pioneer studies for possible linkages between tornadoes and climate change.

He said Arctic ice will melt faster and the jet stream itself will weaken as the Earth warms.

Jeff Masters, director of meteorology for Weather Underground Inc., a private weather-forecasting service in Ann Arbor, said the region's wind shear will keep weakening if the North Pole and South Pole continue to warm.

"Counterbalancing that, we expect instability to increase," Mr. Masters said.

Jeff Trapp agreed some unusual weather events may be on the horizon.

Mr. Trapp is a Purdue University climate scientist who published a 2007 study on that subject. Mr. Del Genio said that report is one of the most significant since the NASA study that came out that same year.

The Great Lakes region's decline in wind shear, according to Mr. Trapp, could be overshadowed by the additional energy for thunderstorms created by a warmer climate.

So it is indeed possible - though not certain - the Great Lakes region could be on the verge of more tornadoes, Mr. Trapp said.

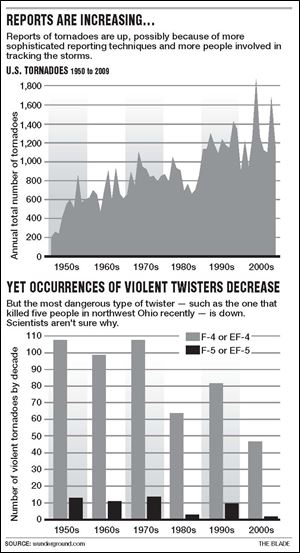

Oddly enough, though, while tornado reports nationwide have been on the rise since the 1950s, those twisters strong enough to be classified as EF-4s or EF-5s - a fraction of the total - occurred less frequently during the 2000s than during the 1990s.

If anything, scientists might have expected more because the climate had slightly warmed.

Some researchers theorize the number of twisters didn't necessarily go up. Because they're usually formed in rural areas, many may have gone unreported in years past, they said.

The technology in detecting tornadoes has become much more precise. Plus, there are more people around to track them - not just because the population has more than doubled since the mid-1960s, but also because there are more people living in areas that were rural decades ago.

"But even in years they're below normal, that doesn't mean you don't have damaging events," Mr. Brooks said. "Very few tornadoes that occur now don't hit anything."

The two most severe types of tornadoes are so rare - often forming only once or twice a year and usually no more than 10 times - that it's hard to make much of their statistics, Mr. Trapp said.

"Underlying this frequency issue is the fact that the tornado intensity classification itself is problematic," Mr. Trapp said. It's based solely on damage, which means that if a tornado causes little to no damage, we have no idea how intense it actually was, and therefore how to count it in the tornado record."

Despite the uncertainty that exists over tornadoes, scientists said there is little doubt that severe weather will become more frequent and intense as the climate warms.

"I think we've got confidence that severe thunderstorms are likely to increase in frequency," Mr. Brooks said.

Gentle soakers that farmers love to keep their fields evenly moistened will occur less frequently, he said.

Instead, there will be more violent episodes of thunder and lightning - even during the winter in the Great Lakes region where, until a few years ago, the thought of more rain than snow in January was unthinkable.

Mr. Masters said Michigan had its first January thunder he can recall in his lifetime this past winter.

A lot of unusual things could happen, he said.

"We can get regional cool spots or hot spots depending on where the jet stream goes," Mr. Masters said.

Thunderstorms, hail, and gale-force winds may not only become more severe and frequent, but also occur during times of year they are usually unexpected.

The insurance industry is "definitely looking at this sort of thing," Mr. Del Genio said.

"We're not talking about the Earth turning into Venus," he said.

"It's not as if Toledo will look that different. The difference is how often unusual things occur and when they do, how extreme they are."

Contact Tom Henry at:

thenry@theblade.com

or 419-724-6079.