Ohio pension laws keep payouts, IDs top-secret

6/22/2010

Last in a series

COLUMBUS - Despite spending more than $4 billion annually on state and local government pensions, Ohio taxpayers have little access to retirement records.

They cannot find out how much individual public retirees receive.

Or how much workers and taxpayers paid toward those pensions pensions.

Or how many years the employees worked.

Or even, in some cases, who's getting the benefits.

State law prevents Ohio's five public pension systems from disclosing many details about individual retirees.

With state leaders talking reform of the pension systems and the possibility that taxpayers may be asked to kick in at least $325 million more annually, that lack of openness raises several questions.

How can taxpayers be assured they aren't being taken advantage of? How well do the pension systems track and catch potential abuse? And how can state lawmakers consider changes without examining the specific details?

''It's outrageous. That is not the kind of transparency that we need in government,'' said Matt Mayer, president of the Buckeye Institute for Public Policy Solutions in Columbus. ''These gold-plated pensions are one of the greatest drivers of public government, and if we can't determine how we are compensating these folks with taxpayer money, we can't fix the ever-increasing cost of government.''

But not everyone is upset. Many defend keeping the financial information private, saying that the retirees are no longer public workers and their pension income isn't the public's business.

''Once that money is paid and it's in the trust fund, the money no longer belongs to the taxpayer,'' said Bill Winegarner, administrator with Partners in Retirement in Westerville, an association of retired public workers in Ohio. "It belongs to the individual. It's their private business."

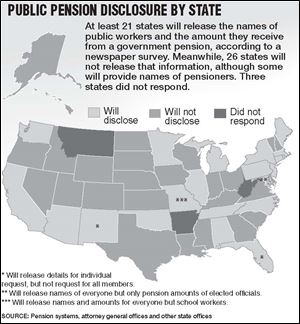

Public pension disclosure by state June 22, 2010" rel="storyimage1" title="Ohio-pension-laws-keep-payouts-IDs-top-secret-2.jpg"/>

Public pension disclosure by state June 22, 2010" rel="storyimage1" title="Ohio-pension-laws-keep-payouts-IDs-top-secret-2.jpg"/>

<img src=http://www.toledoblade.com/assets/jpg/TO66067417.JPG> <b><font color=red>VIEW:</b></font color=red> <a href="/assets/pdf/TO72624622.PDF" target="_blank "><b>Public pension disclosure by state</b></a> June 22, 2010

Ohio's pension systems date to 1920, when the teachers' system was created. The other statewide systems were added later.

In the beginning, financial records for individual retirees were considered public documents. But the state legislature moved in 1965 and 1976 just as it significantly improved benefits - to exempt them from public view.

Today, the Ohio Public Employees Retirement System, State Teachers Retirement System of Ohio, and School Employees Retirement System of Ohio will release the names and addresses of retirees and members, but nothing else.

The Ohio Police & Fire Pension Fund and the Ohio State Highway Patrol Retirement System will release no details on individual retirees - not even their names.

The five systems this year denied public records requests for financial information about retirees. The requests were filed by the Akron Beacon Journal on behalf of the state's eight largest newspapers.

Unlike Ohio, at least 21 states, including New York, Florida, and Illinois consider financial benefits for retirees a matter of public record, according to a newspaper survey. (At least 21 states also prohibit the release of such information. Other states did not return calls for comment.)

Government watchdog groups and the media in the open states have exposed eye-popping pensions and potential abuses - details that are hidden from Ohio taxpayers.

For example, a Chicago Sun-Times investigation last year found 4,000 Illinois public retirees receiving more than $100,000 a year, and three who have topped $3 million in pension benefits since retiring. The newspaper also discovered 14,280 retirees with pensions that pay them more than their final salaries, thanks to automatic 3 percent increases in pension benefits each year.

In California, the watchdog group California Foundation for Fiscal Responsibility created an online database of public retirees with incomes of more than $100,000 a year. At the top is a former city administrator in the Los Angeles suburb of Vernon, who receives $499,674 a year.

The group had to sue to obtain pension records. But the effort, which is ongoing, is worthwhile to expose wrongdoing by public workers and the need for reform, said Marcia Fritz, the group's president.

Taxpayers have been shocked to learn how public employees play the system, she said.

''Seventy-eight percent of likely voters today recognize that pensions are a problem and favor reforming them,'' Ms. Fritz said. ''There was no awareness before.''

She also questioned how Ohio officials can push for reform without examining individual benefits.

''You have to have access to know what you're talking about,'' she said.

In Ohio, nearly 400,000 public retirees receive benefits from the five pension systems. Ohioans now pay more than $4 billion a year toward those benefits.

Records show a growing number of public employees receive annual salaries in excess of $100,000, particularly in the State Teachers Retirement System. As a result, they are qualifying for pensions in excess of $100,000, and with guaranteed cost-of-living raises, their annual retirement benefit could exceed their working wage within a few years.

However, the average annual pension benefit ranges from $10,552 for School Employee Retirement System retirees to $38,555 for State Teacher Retirement System retirees, according to the pension systems' financial reports. Police and firefighters receive an average $36,243 and $34,710, respectively.

Retirees with the Public Employees Retirement System received $20,214 a year, and Highway Patrol retirees got $38,076.

Unless they had another job in the private sector, they receive no Social Security benefits.

There are plenty of stories about public workers playing the system to their benefit. Currently, pensions are awarded based on the highest three years of salary - although there are proposals to raise that to five.

Some individuals spike their salaries with overtime or other pay in those final years to boost their pensions. Others may work low-paying jobs for years and then snag a high-paid political position just before they retire, meaning they paid little toward their large pension check.

In other cases, workers retire and go immediately back into the same public job, improving their personal income by collecting a paycheck and pension at the same time. State pension officials estimate that about 31,700 retirees, or nearly one in 10, have retired and gone back into a public job - so-called ''double-dippers.''

There are no estimates on how many others have retired and taken jobs in the private sector at a time that 652,000 Ohioans are looking for work.

Last year, Summit County Council permitted Mary Ann Kovach, chief counsel in the prosecutor's office, to be rehired part time after she retired in December. She is now able to collect her government pension and a county paycheck.

She is being paid $53.16 an hour. Her previous annual salary was more than $110,000.

Without having access to financial records, it's unclear how pervasive these practices are.

Even some state lawmakers and pension board members said they were unaware that financial data aren't available for scrutiny by the public.

State Sen. Kirk Schuring, a Republican from Stark County's Jackson Township, questioned why the financial details are withheld. He is on the Ohio Retirement Study Council, which provides oversight for the pension systems.

He noted that salaries of public workers are available to taxpayers. ''Whatever the law is that pertains to active employees should also apply to retired, ex-employees,'' Mr. Schuring said. ''Why shouldn't it?

''The employer contribution is paid by the taxpayer. The employees will argue that their contribution is paid out of their salaries. But there is a nexis between the taxpayer and the retiree.''

State Reps. Matt Lundy (D., Elyria) and Stephen Dyer (D., Green) - both former journalists who have focused on public-records issues since being elected - said it would be easier for lawmakers if the financial details were available.

''You can't make a tough decision if you don't have all the information,'' Mr. Lundy said, adding he too was unaware that the financial data were not available to the public. ''I think it's a very valid argument. It's not a taxpayer-friendly system.''

Mr. Dyer said he and Lundy are drafting legislation to require more openness.

Tom Curtis, a retired Plain Local Schools teacher who lives in North Canton and has been an outspoken critic of fund managers, said he's not surprised such information is withheld from the public.

''It's a good old boys network at the top and they pretty much do what they're going to do,'' he said.

Scott Maynor, former chairman of the Ohio Police & Fire Pension Board of Trustees and a lieutenant with the Lyndhurst Fire Department, said he understands the public's interest.

The board receives periodic reports showing averages and a graphic illustrating pension amounts as a bell curve.

When he saw a ''couple of ridiculous'' high-end pensions, Mr. Maynor admitted he wondered how they came about and whether the workers paid enough into the system to warrant the amount. But he didn't wonder who is receiving them.

Overall, the pension averages are reasonable, he said.

William Estabrook, executive director of the Ohio Police & Fire Pension Fund, said he wouldn't have a problem with making some financial records public. As someone who has worked four decades in public jobs, he's used to his salary being available to taxpayers.

''It doesn't bother me,'' he said. ''My neighbor probably knows more about what I make than I do. But I do have grave concern for public safety folks, because they cross the criminal element and need a level of protection.''

For example, he said, he wouldn't want to see addresses of former law-enforcement officers, names of spouses, or medical records made public. .

The Ohio Public Employees Retirement System, the largest pension system with nearly 171,000 retirees and the one most ripe for political abuse, did not respond to multiple requests for comment about the issue of public records.

Aristotle Hutras, executive director of the Ohio Retirement Study Council, said the topic of public access never has been discussed in the 20 years he has led the organization.

He also said he doesn't believe the information is being hidden from taxpayers.

If people want to know how much a retiree receives, they can find his final salary and then estimate the pension, he said.

But that process would be lengthy and possibly inaccurate. It also would be time-consuming to research and produce individual data for nearly 400,000 public retirees.

Mr. Estabrook added that the Police & Fire fund keeps an eye out for potential abuses.

Last year, the pension board approved a measure to ban spiking in the final three years of employment. In some cases, workers pack on overtime to boost their salaries and, ultimately, their pensions.

The prohibition limits pay increases for pension purposes to 10 percent a year in the last three years. The move, which takes effect this year, is expected to save $800,000 a year.

Only six of his fund's retirees make more than $90,000 a year, Mr. Estabrook said. The majority receive between $24,000 and $38,000.

Jim Winfree, executive director of the School Employees Retirement System of Ohio who retired at the end of April, said pension leaders take their oversight responsibilities seriously and have many internal controls to watch for potential abuse.

That includes monitoring members' salaries to look for unusual jumps, and external and internal auditors conducting periodic reviews of individual benefit cases to make sure payments are accurate. ''Our system might be tougher than some others,'' Mr. Winfree said. ''We want to make sure we're as accurate as we possibly can be.''

But even some retirees are curious about what the financial details would reveal.

Valerie Rodgers, executive director of the Retired School Employees of Ohio Inc. in Columbus, said there is concern that some retirees are playing the systems to their financial benefit, which hurts the overall system. For example, some retirees aren't paying enough into the systems to warrant their high pensions, she said.

''We can't have people robbing the systems,'' Ms. Rodgers said.

Contact Rick Armon at:

rarmon@thebeaconjournal.com,

or 330-996-3569.