SHUT DOWN & SHIPPED OUT

Factory closings rock the region as other states gain from our pain

9/26/2010

This is the first of three parts

With his job slated for elimination, Glen Ramsey faces an uncertain future. His employer, Continental Structural Plastics in North Baltimore, had planned to move the plant but opted to downsize instead.

NORTH BALTIMORE, Ohio - What was touted as a win for the state of Ohio is still a loss for Cygnet resident Glen Ramsey.

Mr. Ramsey, 61, will lose his $19.90-an-hour maintenance job within a matter of months after 12 years at Continental Structural Plastics in North Baltimore. The 214-employee factory was slated for closure and relocation to Huntington, Ind., but approval of a new contract by union members on Sept. 11 managed to keep the plant open and save an estimated 60 jobs.

Though a positive announcement for northwest Ohio, which has been bleeding factory work to other states and countries, Continental's decision to downsize rather than close its North Baltimore plant likely represents an early retirement and loss of health insurance for Mr. Ramsey.

For the region, it could've - and has - been much worse.

Since Jan. 1, 2009, four northwest Ohio factories have closed, shipping their work to Indiana and costing the state 319 jobs.

In the same period, a Blade investigation found, at least 11 other manufacturers employing about 1,900 people in the region have closed and shipped work to North Carolina, Tennessee, Illinois, and elsewhere within the United States.

"It's like they're taking off to a Third World country," Mr. Ramsey said. "I don't see much difference between Indiana and Mexico, as far as shipping our jobs to other countries or other places."

Massive job losses caused by factory closures are nothing new in northwest Ohio and southeast Michigan. Going back to 2000,

The Blade found about 140 factories with 20 or more employees that closed in northwest Ohio, totaling about 18,000 lost jobs. More than two dozen factory closings - costing about 3,500 jobs - were counted in Lenawee, Hillsdale, and Monroe counties in southeast Michigan.

County by county, town by town, there are thousands of stories of homes and health insurance lost, slashed salaries for those lucky enough to find new jobs, and years of emotional distress for those who were handed permanent pink slips.

Restaurants and retail shops across the region that relied on those factory workers shut their doors as well, and dozens of local governments are battling huge budget deficits caused by dwindling tax receipts.

In short, factory closures and manufacturing job losses are as much a cause as they are an effect of the recession that has devastated Main Streets everywhere.

A much longer discussion, one that has burrowed its way to the center of Ohio's two most high-profile political races this fall, is about why this happened.

Democrats are accused of fostering a high-tax, overregulated business climate in the state; Republicans are blamed for supporting unfair and harmful trade agreements, while corporations pursue the highest profits and lowest salaries for their employees.

"I'm just wondering how I'm going to survive and keep my house," said Linda VanScoder, 56, who lost her job Aug. 9 making $16.63 an hour at Thomas & Betts Corp., an electrical fittings maker that is closing its Bowling Green plant and shifting work to Portland, Tenn.

"It seems like all the jobs around here are getting sent to other states and I just don't understand why," she said.

The Blade scoured federal filings and statistics, old press clippings, and information provided by individual cities and villages to create a 10-year database of factory closings in a 21-county region surrounding Toledo.

In most cases, the closures and relocations resulted in lost jobs. In a few instances, the factories moved to an area close enough that most workers kept their jobs, but the tax revenue was lost for the community where the factory was shuttered.

Not included in the database are still-operating factories that have significantly downsized their work forces through mass layoffs. Overall, Ohio lost about 430,000 manufacturing jobs from 1990 through July, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Michigan has lost 460,000 manufacturing jobs over the same period.

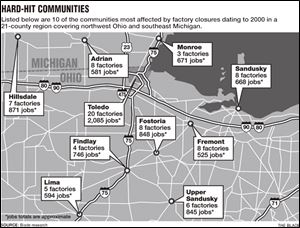

According to The Blade's investigation, Toledo has lost at least 20 factories in 10 years. The city lost a General Mills cereal plant with 468 employees in 2002. The next year, Toledo lost Baron Steel with its 124 remaining workers. In 2005, the venerable Toledo shipyards suffered a blow when Toledo Ship Repair Co. closed and left 86 workers without a job. Some of the best-known ships on the Great Lakes, including the icebreaker Mackinaw, were launched from Toledo's docks.

Toledo has averaged about two factory closings a year since 2001, with New Mather Metals (168 jobs), MacLean Flowform (52 jobs), and Textileather (160 jobs) all closing since Jan. 1, 2009.

Elsewhere in the region, Fostoria (eight factories, 848 jobs), Sandusky (eight factories, 668 jobs), and Fremont (eight factories, 525 jobs) have suffered huge losses in northwest Ohio. Adrian (eight factories, 581 jobs) and Hillsdale (seven factories, 871 jobs) have been hit hard in southeast Michigan.

With skyrocketing factory closings, unemployment rates have soared. Williams County in northwest Ohio led the entire state in average unemployment (15.7 percent) in 2009, while Hillsdale County (17.9 percent) had one of Michigan's worst jobless rates last year.

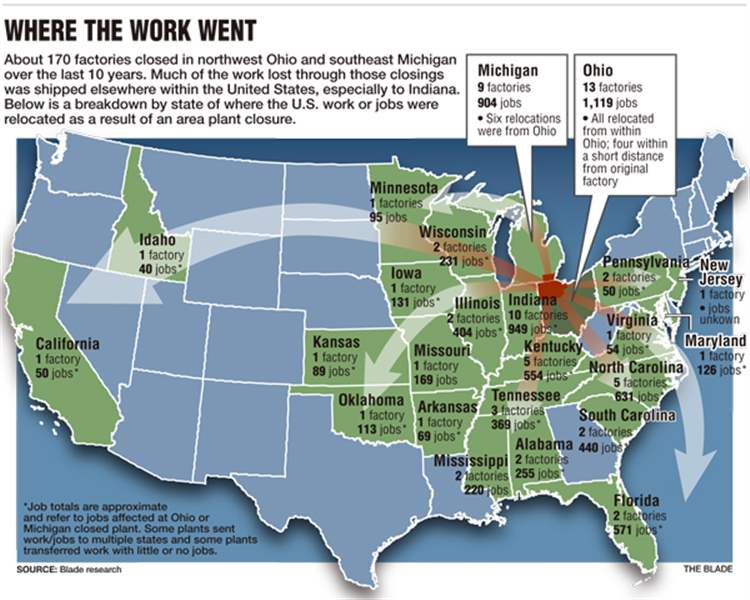

Of all the factories that closed, in at least 61 cases, jobs or the work done at the closed plants were moved elsewhere within the United States. The Blade counted 47 factory closings that resulted in work being shifted to different countries.

Twenty-three states benefited from factory closings in the Toledo area, with neighboring Indiana receiving jobs or work from at least 10 plant closures - the most of any state.

At least 27 factories were sold no more than five years before they closed, and at least 70 closed factories were owned by companies based outside their local communities.

In recent interviews with business executives and explanations given in past published statements, the most common reason cited for moving a plant was the need to consolidate and rein in costs.

"It's corporate speak for cutting payrolls," economist Robert Reich wrote in an e-mail to The Blade. Mr. Reich, a public policy professor at the University of California-Berkeley, was President Bill Clinton's labor secretary from 1993 to 1997 and was a member of President Obama's economic transition advisory board after the 2008 election. "Corporations are set up to maximize profits. They'll be good citizens only if the PR value exceeds the cost."

Mitch Roob, Indiana's secretary of commerce and director for the Indiana Economic Development Corp., said his state's low business costs are a main contributor to its recent hot streak.

Not only have Ameri-Kart (Fostoria, 54 jobs), New Millennium Building Systems (Continental, Ohio, 110 jobs), Triton Metal Products (West Unity, Ohio, 55 jobs), and Coupled Products (Upper Sandusky, 100 jobs) all left for Indiana in the last two years, Mr. Roob said his state has won business and jobs 62 times from other states since a national recession unfolded in late 2008.

"We just fare better than others when it comes to low costs," Mr. Roob said. "Companies know what they pay in Indiana and they know what they pay in Ohio. Being low cost when times are tough is important."

Mr. Roob's explanation is one sounded again and again by Republicans, including U.S. Senate candidate Rob Portman and GOP gubernatorial challenger John Kasich, who say the business climate in Ohio fostered by Gov. Ted Strickland and Democratic Senate hopeful Lee Fisher is rife with high costs and regulations.

Mr. Strickland and Mr. Fisher, his lieutenant governor, vehemently disagree, accusing Mr. Kasich and Mr. Portman of supporting free-market, corporate-friendly policies in Washington that have cost Ohio hundreds of thousands of jobs.

While Indiana's unemployment rate in August was a hair higher than Ohio's (10.2 percent in Indiana compared to Ohio's 10.1 percent), Indiana gained about 40,000 jobs since August, 2009. Ohio gained about 7,300 jobs since August, 2009, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

When it comes to the cost of manufacturing, it's questionable how much cheaper it is to make things in Indiana than in Ohio.

In 2009, the average salary for manufacturing employees in Ohio was $43,011, less than Indiana's average of $45,643, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

However, electricity costs are much higher in Ohio compared to Indiana - 6.19 cents per kilowatt/hour for industrial users in Ohio versus 5.71 cents in Indiana, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Plus, average worker compensation rates per $100 of payroll for manufacturing are $3.37 in Ohio versus $2.22 in Indiana, according to officials from both states.

Comparing taxes is harder.

Indiana's personal income tax rate of 3.4 percent is lower than Ohio's top bracket of 6.24 percent, but Ohio has eight lower brackets that allow most factory workers to pay taxes comparable to their Indiana counterparts.

Indiana also charges a flat tax on corporate income of 8.5 percent. Ohio, having just completed a revamping of its tax structure that began under Republican Gov. Bob Taft and was carried out under Mr. Strickland, now charges its corporations a 0.26 percent tax on commercial activity - essentially a tax on gross receipts from in-state business transactions, including sales.

Ohio manufacturers also no longer pay taxes on equipment, machinery, and inventory, nor do they pay taxes on business conducted outside the state.

Beginning this year in Indiana, property taxes for businesses are capped at 3 percent of assessed value. Indiana businesses also do not pay taxes on gross receipts or inventory.

"We deal with [taxes] with companies on an individual basis, and I will tell you that when we're talking about tax structures, Ohio is very competitive," said Mark Barbash, the chief economic development officer in Ohio.

In at least three recent cases of an Ohio factory closing and/or moving work to Indiana, the company received cash to cross into the Hoosier State.

In a press release dated Dec. 8, Triton Metal Products Manager John Freudenberger said the company was relocating to Indiana because it "is a very progressive state that has many good programs and resources in place for new businesses." The company was awarded up to $670,000 in performance-based tax credits and grants by Mr. Roob's development corporation.

Continental Structural Plastics was promised $2.5 million in incentives to move production from North Baltimore to its Huntington, Ind., plant.

And Coupled Products received $793,000 in state incentives to relocate from Upper Sandusky to Columbia City, Ind.

Upper Sandusky Mayor Scott Washburn said development officials from Ohio couldn't compete with their Indiana counterparts.

"It would be fair to say that Indiana was more aggressive," said Mr. Washburn, a political independent who was involved in negotiations with the company. "They [Indiana officials] were ready to pull the trigger now."

Mr. Washburn said Ohio officials were too slow and cautious in putting together an incentives package for the company. He said there were "too many hoops to jump through" and "too much red tape" from Ohio officials to compete with Mr. Roob's offer.

Ohio development officials confirm that they were talking to Coupled Products, but no incentives were offered. The state also said it was not approached to work with Triton Metal and didn't offer Continental Structural Plastics any incentives before the company's announcement that it was leaving for Indiana because the company couldn't commit to retaining enough jobs to qualify for cash assistance.

The speed at which Mr. Roob can strike a deal is also a factor.

"In many respects, the economic development program in Ohio is far more robust than ours," Mr. Roob said. "We move really fast. If you call me at 9 a.m., I can have an offer to you by 3 p.m. We try to move at the speed of business."

In a tale-of-the-tape comparison between Indiana and Ohio, Mr. Roob's operation is indeed the smaller dog in the fight.

The Indiana Economic Development Corp. serves as the state's development arm with 65 full-time employees and an annual budget of $37.3 million. About $10.4 million of Mr. Roob's budget is set aside for administrative functions, and the remaining $27 million is set aside for grants to businesses.

The Ohio Department of Development, which the Republican gubernatorial challenger Mr. Kasich has said would be eliminated if he's elected, has 408 employees with a $1.15 billion budget for the current fiscal year.

A representative for the department of development said she could not provide a breakdown of administrative costs and grant funds for this year.

But the state's development department reports $4.47 billion in public funds committed to incentives for businesses since 2006, leveraging $21.18 billion for Ohio.

Mr. Barbash, Ohio's top economic development officer, acknowledged that numerous factories have closed in northwest Ohio and relocated work to other states. He could not produce statistics detailing which companies relocated work from other states to Ohio, but he did provide specific examples of job retention and creation successes in northwest Ohio, including:

•Schindler Elevator choosing to remain in suburban Toledo in 2007 instead of relocating to New Jersey or Illinois, retaining at least 140 jobs. Schindler also chose to put a new research and development center in Springfield Township, adding 80 jobs. Ohio offered Schindler an incentives package valued at more than $11 million.

•Chase Brass and Copper in Williams County's Holiday City chose to maintain 272 jobs there this year and potentially create 25 additional jobs. The company was awarded tax credits and grants from the state totaling $172,000.

•Cooper Tire decided to continue operating its Findlay plant with 1,100 employees in 2008 instead of shifting work to Georgia, Arkansas, or Mississippi.

•Whirlpool Corp. elected last year to purchase a W.C. Wood Co. plant in Ottawa, Ohio, a facility with 215 employees that was slated for closure. Whirlpool expected to employ up to 190 at the Ottawa plant this year.

Ohio development officials said they were involved in retaining and recruiting efforts with Cooper Tire and Whirlpool, but did not elaborate.

In 2008, Whirlpool announced plans to move manufacturing operations from Tennessee to its Findlay location, creating an additional 263 jobs. State officials awarded Whirlpool's Findlay division with a job creation tax credit valued at $907,000 over seven years.

Sypris Technologies, a maker of trailer axles with a unionized, 232-employee plant in Kenton, Ohio, that closed last year, claimed it shifted operations to "right to work" North Carolina because salary and benefit costs for employees were 46 percent lower there.

Leggett & Platt Inc., which closed a plant with 146 unionized workers in Archbold, Ohio, in 2006, moved operations to Chattanooga, Tenn., to a nonunion facility. Former Archbold workers say Leggett & Platt planned to pay Chattanooga workers a starting wage of $8 to $9 per hour, compared with the $17 an hour paid on average to its northwest Ohio workers.

Companies don't often admit it, and economic development officials only acknowledge it in private, but at least some businesses pick locations based on the presence and strength of organized labor.

"A union mentality, even if it's a nonunion shop, is a death knell," said Indiana's Mr. Roob, whose state does have some strong union pockets surrounded by large areas of little or no organized labor. "We want to foster that perception. Indiana is a southern state misplaced in the Midwest."

Despite its reputation, Indiana is not among the country's 22 "right to work" states - or states where employees cannot be required to join a union as a condition of private employment.

Of the four factories northwest Ohio has lost to Indiana in the last two years, Ameri-Kart closed a union facility here and shipped work to a nonunion facility in Indiana. Continental Structural Plastics, which decided to trim its unionized work force in North Baltimore from 214 to 60, is shifting work to its nonunion facility in Huntington, Ind.

The Blade identified at least 21 factories in Greater Toledo that closed and shipped work to a "right to work" state, which are located mostly in the south.

Stan Greer, a senior research associate for the National Institute for Labor Relations Research, said "right to work" laws are a large factor among many in attracting manufacturing work to a state.

Mr. Greer, who is also a spokesman for the National Right to Work Committee, said states with a strong union presence - particularly in the public sector - tend to have higher taxes and more regulations on business.

Citing data from the U.S. Department of Commerce, Mr. Greer said the 22 "right to work" states saw a 20.9 percent increase from 2000 to 2008 in real manufacturing output. He said the other states experienced a 6.5 percent growth.

Indiana experienced a slight growth in real manufacturing output of 1.2 percent from 2000 to 2008, while Ohio and Michigan endured declines of 6.6 percent and 11 percent, respectively.

"We would never say it's the only factor," Mr. Greer said. "Certainly tax policies and regulatory policies are significant, the location, natural resources, and location on various trade routes. But certainly there is a clear advantage for the 'right to work' states."

Ken Lortz and Tim Burga spend their days fighting against companies looking to skirt unions. But Mr. Lortz, regional director for the United Auto Workers in Ohio, and Mr. Burga, chief of staff for the AFL-CIO in Ohio, both cite the negative effects of international trade agreements - and not corporate union-dodging or union-busting - as the primary reason for the exodus of factory work.

"You can't take trade out of it," Mr. Lortz said.

Beginning with the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement under President Bill Clinton and continuing with numerous similar deals with other nations, organized labor has long decried the ill effects these agreements have had on American manufacturing.

Far cheaper wages, much lower taxes, and lax regulatory atmospheres entice companies to move manufacturing operations overseas, causing companies which stay in America to search for rock-bottom labor costs to remain competitive.

According to the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, 5,055 displaced workers in northwest Ohio qualified for federal assistance in 2010 because of a job loss caused by free trade. In those cases, the worker's job was either shipped directly out of the country, was shed because of a rise in imports of the product the company makes, or dropped because of loss of business from a customer whose employees also qualified for federal assistance.

Of the local factory closures identified by The Blade, at least 31 resulted in work or jobs being shipped to Mexico, including a 125-employee Commercial Vehicle Group plant that closed in Norwalk earlier this year because of a customer's shift to Mexico.

"The whole idea of raising the standard of living in Mexico so they can buy a Hoover vacuum made in Canton just didn't materialize," said Mr. Burga, of Ohio's AFL-CIO.

Mr. Strickland voted against NAFTA when he was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives in 1993. He also voted against granting China normal trade relations status with the United States.

Mr. Kasich and Mr. Portman both voted in favor of NAFTA and trading with China as U.S. House members, although Mr. Portman also scrutinized and accused China of unfair trade practices when he served as President George W. Bush's trade representative.

With the U.S. overall trade deficit around $289 billion this year, thousands of job losses are being credited to America's trade deficit with China that now stands around $145 billion for 2010. In March, the liberal Economic Policy Institute released a study showing that the United States lost 2.4 million jobs as a result of its trade deficit with China from 2001 through 2008, including 91,800 jobs in Ohio.

The Chinese are often accused of holding down the value of their currency against the dollar, closing off their markets for exports, and product dumping to flood markets in the United States.

John Essman, who owned a small pumps, valves, and fittings plant that closed in Bryan, Ohio, in 2003, said his company fell victim to Chinese production.

"There's no way you could compete with them there," he said. "Sometimes, I could buy a completed product cheaper than I could make it myself."

The Blade's survey shows that at least 54 plant closures in northwest Ohio since 2000 were directly related to a slumping automotive sector, supporting the commonly held belief that problems with the Big Three American car companies have greatly affected the region.

State Democrats argue that Governor Strickland's investments in alternative energy research, development, and worker training - including millions of dollars funneled by the state to the Toledo area - will play a primary role in Ohio's eventual economic rebirth. Those same politicians and labor leaders also say that as Detroit reinvents itself, second-tier auto suppliers in Ohio and Michigan will get a boost.

But for mayors such as Upper Sandusky's Mr. Washburn, whose community of 6,362 people has lost 845 factory jobs in five years, losses in traditional manufacturing are frustrating. It's hard for him to consider global factors or bets made on a high-tech future when jobs are shifting from his city to Indiana.

"What we're doing's not working," Mr. Washburn said. "I hear these politicians run on: 'We're all about what happens on Main Street, not Wall Street.' They keep saying they're working for Main Street, for small-town America.

"But we never see them."

Contact Joe Vardon at:

jvardon@theblade.com

or 419-724-6559.