Northwest Ohio labs lack funding to address water threats

10/11/2010

As Ohio winds down its first season of tracking potentially lethal blue-green algae statewide, questions arise about where researchers will get money to stay ahead of the public-health threat next summer.

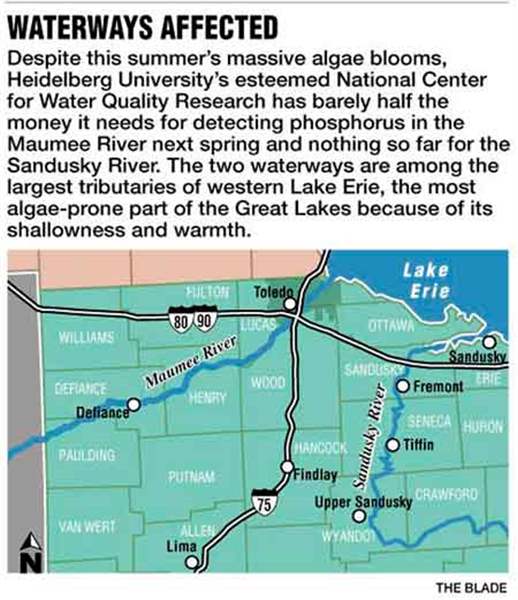

As of last week, Heidelberg University's esteemed National Center for Water Quality Research — which has generated area phosphorus data for countless Great Lakes scientists since the 1970s — had barely half the money it needs to do its annual spring sampling of the Maumee River.

It had none for the Sandusky River.

The Maumee and the Sandusky, cornerstones of that lab's program, are two of the largest and most important tributaries of western Lake Erie, the Great Lakes region's most productive for fishing.

Western Lake Erie — affected by toxic algae almost annually since 1995 — also is an area that economic development officials believe has never tapped its full potential for tourism and recreation.

Likewise, many questions are emerging about how the cash-short state of Ohio will afford a more refined and sophisticated algae-tracking program, especially if next summer's outbreak is anything like this year's.

With bills still coming in, state officials conservatively estimate they have spent at least $413,000 on gathering samples, sending them off for analysis, and notifying the public where the greatest known risks are present. That figure doesn't include staffing time, which three agency directors told The Blade last week was enormous.

None of that was budgeted.

Testing for algae at Ohio's 11 public water treatment plants now costs the state about $5,800 a week, and the algae are likely to linger through at least the end of October, officials said.

Then, it will be months of huddling to see how next summer's situation can best be addressed on a shoestring budget and with something other than an impromptu response.

“Considering that we had to do a lot of this on the fly, I think it went pretty well,” said Chris Korleski, director of the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency.

“This was scary,” he said. “We were getting reports of individuals being seriously impacted. I'm very proud of what the three agencies did to try to address this. It's very possible we're going to be dealing with a similar situation next summer.”

Noted for research

Tiffin-based Heidelberg's National Center for Water Quality Research has produced work cited at Great Lakes conferences for years.

It has monitoring stations along the River Raisin near Ida, Mich., along the Portage River near Woodville, along the Cuyahoga River south of Cleveland, and in the Great Miami, Scioto, and Muskingum watersheds in southern Ohio. But its bread-and-butter work is in the Maumee and Sandusky watersheds in northwest Ohio, according to the lab's director, Ken Krieger.

Testing along each of the waterways is funded separately, he said.

The Maumee and the Sandusky need about $40,000 per river for Heidelberg to maintain its current level, Mr. Krieger said.

The Maumee sampling money consists of $21,000 in grant money the National Science Foundation gave to the University of Michigan, which has agreed to forward it to Heidelberg for collaborative research.

The Heidelberg lab is anticipating at least partial funding for the Sandusky in January but doesn't have anything yet, Mr. Krieger said.

“Many groups and agencies are using our data,” Mr. Krieger said. “We're getting a lot of verbal support, but not a lot of monetary support.”

Even as algae became a high-profile issue this summer in response to the public outcry over massive blooms in Grand Lake St. Marys and western Lake Erie, Mr. Krieger said he is spending an inordinate amount of time scrambling for grant money.

‘Stopgap' grant

This year's discovery of a record phosphorus level in the Maumee was made possible by what Mr. Krieger described as a one-year “stopgap” grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Natural Resources Conservation Service.

The state of Ohio is not currently one of the lab's funding sources.

The lab received state money in the past from a legislative earmark.

But the Strickland administration said last week it ended that out of fear that the earmark “would directly take away needed funds from the Soil and Water Conservation Districts who carry out the work to improve water quality.”

“So, while the study of phosphorus is important, we had to prioritize funding the actual work to address and minimize phosphorus and sediment from entering into our waterways,” Amanda Wurst, a spokesman for Gov. Ted Strickland, said. “There is nothing that prevents Heidelberg from applying for state grant programs, which would not have a negative impact upon the funding for county soil and water conservation districts.”

So even with algae reaching record levels in Ohio this summer, one of the leading institutions investigating a primary cause of it is left scrambling for funds.

Phosphorus, which is found in substances ranging from farm fertilizers to animal manure to human sewage, is the main algae nutrient.

“They could be providing at least partial funding,” Mr. Krieger said. “Right now, the state of Ohio is not funding any of our tributary loading sites.”

Blue-green algae surround a Meinke Marina buoy in Lake Erie in Oregon. Prolonged heat wave this year created massive blooms in western Lake Erie and several inland bodies of water.

Satellite proposal

About this time last year, state legislators considered a proposal by Robert Vincent, a Bowling Green State University researcher, who said he would be able to help the state be proactive in identifying the most algae-prone areas via satellite imagery at a cost of $175,000 this summer.

Lawmakers, in the midst of a budget crisis, declined.

Officials relied heavily on observations made by ordinary homeowners and boaters.

As public outcry intensified, a makeshift pilot program was thrown into place by the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, and the Ohio Department of Health.

Mr. Korleski said the experience taught him “how well state agencies can work together in a crunch.”

This summer's algae resulted from what Dr. Alvin Jackson, the state health director, described as a “perfect storm” of factors.

Heidelberg's lab detected the highest level of phosphorus at the Maumee River's monitoring station near Waterville since record-keeping began in 1975. It also found the Sandusky River posting its second-highest level at its monitoring station near Fremont.

With the ingredients for growing algae in place, prolonged heat waves created massive blooms in western Lake Erie and several inland bodies of water — most notably, Grand Lake St. Marys, which a state EPA spokesman, Dina Pierce, said was believed to be among the nation's 10 worst spots for algae this summer.

Officials scrambled to find the most dangerous places, with minimal staffing and a time crunch that made it impossible to test all of Ohio's 400-some bodies of water.

Chance observation

Ohio's first public-health advisory along Lake Erie in decades, if ever, came as a result of chance: Two state EPA employees returning from a gathering at Ohio State University's Stone Laboratory on Gibraltar Island near Put-in-Bay, stunned by the lake's pea-green hue, drove immediately to the closest state-owned facility, East Harbor State Park, to grab samples. The water was so green that officials took the rare tack of posting the advisory as a precaution before receiving results on the samples they had sent off to be analyzed.

For the rest of the summer, interns collecting bacteria samples from Lake Erie beaches were instructed to get extra samples for algae analysis.

Several data gaps existed. For example, Port Clinton City Beach — a popular spot in one of Lake Erie's most visited tourism-based communities — was tested for bacteria but not algae.

Municipal officials there said they thought both contaminants were being tested. The Blade's own sampling showed water near that beach had a level of the toxin microcystin that was nearly five times the World Health Organization's threshold of 1 microgram per liter for drinking water, but below the 20 micrograms per liter threshold for recreational water.

State health department records show 45 human illnesses associated with various algae toxins were investigated this summer. Nearly half — 21 — of the cases originated at Grand Lake St. Marys. Lake Erie was second with 10, followed by Burr Oak State Park with seven.

The bottom line is nobody died, state officials said.

Serious threat

The state health department's Dr. Jackson said the public-health threat of algae blooms is indeed serious. “Some of the most potent toxins known are produced by these blue-green algae,” he said.

Health officials have a hard time classifying cases because of the myriad symptoms. Those who were investigated for exposure complained of nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, light-headedness, neurological problems, and skin rashes. Some even had trouble breathing, he said.

“When we first were presented this, we really didn't have a case definition for it,” Dr. Jackson said. “Our biggest challenge was to come up with a case definition to have a common definition.”

Although nobody knows what the future holds, many agree that the situation does not bode well for Ohio's chances of avoiding similar algae outbreaks.

At stake are the state's hopes for diversifying its economy through more recreation and tourism, as well as shoreline property values and public health.

“We learned that algae can be evil,” said Sean Logan, director of the state's department of natural resources.

The agencies found that it was a challenge to collect data and make timely decisions on where to post advisories, knowing their methods were imperfect yet essential for protecting public health.

Said Mr. Korleski: “We have a big problem here. The people of Ohio need us.”

Double whammy

Many scientists believe the long-anticipated effects of climate change are now becoming more apparent in the Great Lakes region with warmer temperatures and more frequent storms. Those conditions are a double whammy that could lead to more phosphorus runoff and more algae.

“You can't assume any year's going to be a normal year,” Mr. Krieger said.

Experts fear runoff will get worse if the region's development continues to sprawl and greater demands are placed on the agriculture industry to consolidate food production.

The state of Ohio didn't anticipate this year's costs. Funding for tracking algae on the state level is unclear.

“These types of decisions will need to be made in the context of the next budget as it is considered next year,” Ms. Wurst said.

One possible revenue source is President Obama's Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, which is expected to be funded at $475 million annually.

“The restoration initiative is moving increasingly toward financing real on-the-ground and in-the-water action to reduce polluted runoff,” according to a statement issued by Cameron Davis, senior Great Lakes adviser to Lisa Jackson, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency administrator.

Mr. Korleski agreed the status quo isn't working, neither from a funding nor a pragmatic standpoint.

“I wouldn't want to mislead anybody into thinking we have the resources to go out and sample every lake,” Mr. Korleski said.

More aggressive efforts to control runoff may have to be enacted, he said.

“Regulation is a tool that needs to be used wisely,” he said. “As [Ohio] EPA director, [more] regulation is something we'll have to be looking at.”

Contact Tom Henry at:thenry@theblade.comor 419-724-6079.