Over 175 years, The Blade has been a constant force in the city it serves

12/19/2010

Blade owner and publisher Paul Block Sr. and wife Dina attend The Blade's 100th anniversary event Oct. 26, 1936, which actually was held 101 years after the newspaper's first issue.

To view the 175th Anniversary special section: VIEW: The Blade' 175th Anniversary Special Section.

To locate the section, first register and log in to the eBlade. Press the "E" key on your keyboard, and an "Editions" menu will appear on the left side of your screen. In the drop-down menu below the word "Editions," select "The Blade 175th Anniversary A."

A drop-down navigation bar at the top of the browser window allows you to change page-view aspects such as zoom and the number of pages shown in your browser window.

For going on a year now, we've been partying like it's 1835.

On this date 175 years ago — Dec. 19, 1835 — the first edition of the Toledo Blade rolled (if newspapers rolled back then?) off a hand-operated press.

Eight score and 15 years later, The Blade is Toledo's oldest continuous business. The paper and the city have engaged in various events during 2010 to commemorate The Blade's milestone, culminating with today's special anniversary edition.

James Earl Jones, the actor with the commanding, iconic voice, offers a memorable monologue toward the end of the 1989 hit Field of Dreams in which he says: “The one constant through all the years, Ray, has been baseball. America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It has been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt, and erased again. But baseball has marked the time.”

If one were to change just a few words — say, substitute “The Blade” for “baseball” and “Toledo” for “America” — what you'd have is the foundation of an enduring relationship between a newspaper and its community.

The first edition of The Blade from Dec. 19, 1835.

The Blade is more than a year older than its home city (Toledo was incorporated as an Ohio city in 1837) and literally has been there to chronicle each of the city's twists and turns through history — from Toledo's first tax levy on personal property in April, 1837, to its hosting of the boxing world's heavyweight championship bout in 1919, to the deadly Auto-Lite labor strike in 1934, to Elvis Presley's hip-shakin' visit in 1956, to the city's triumph in retaining Jeep in 1997.

But The Blade has done more for Toledo than mark the time. It has on occasion set the city's agenda or taken up a cause at home and abroad. Among those causes were the abolition of slavery, the banning of alcohol and later the repeal of Prohibition, the passage of one of the country's first municipal income taxes in Toledo, the establishment of a port authority, the transition to a strong mayor form of government in Toledo, and most recently the rescue of puppies previously destined for death at the Lucas County dog pound.

Toledo and its greater community has indeed rolled by like an army of steamrollers; it undoubtedly has been erased like a blackboard and built again. In some cases, The Blade was supplying the steam and holding the eraser, but was there nonetheless. And for its work, The Blade was awarded journalism's highest honor — a Pulitzer Prize in 2004 — and has received its share of scorn and ridicule.

So as The Blade marks its birthday today with a look at its own history and a glance toward its future in the digital age, the newspaper can celebrate its ability to hold true to something its first editor, George Way, wrote in the newspaper's first editorial — that the paper shall be “an instrument better fitted for long and enduring service.”

“The history of Toledo and the history of The Blade, not exactly, but in large part, go together,” said John Robinson Block, publisher and editor-in-chief of The Blade and its sister paper, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. The Blade has been owned by Mr. Block's family since 1926.

“I've always thought our job was to report the news the best we could each day and that awards were secondary,” Mr. Block continued. “What I take satisfaction in is nobody can come up with any Blade involvement, crusade, campaign — anything we've given ink to and cared about — that there was any motivation other than to improve Toledo.”

Century mark

When the stuffed turkey and mashed potatoes are gone, and the holiday dinner table is reduced to empty pie plates and crumpled napkins, what comes next is often a round or two of family stories — some of them new and others passed on from generation to generation.

It's no different for Blade milestone celebrations, when the paper's beginnings as an ally of the Whig political party, its reputation as “Nasby's Paper,” and the writings of Grove Patterson are relived.

But for the past three big Blade birthdays — its 125th anniversary in 1960, its 150th in 1985, and its 175th today — one story retold is how the paper missed its own 100th birthday.

Blade owner and publisher Paul Block Sr. and wife Dina attend The Blade's 100th anniversary event Oct. 26, 1936, which actually was held 101 years after the newspaper's first issue.

The Blade did publish a 100th anniversary edition in October, 1936, believing at the time that its first edition was published in November, 1836. And even that belief was not based on physical proof, as the only copy of early editions that had been found was that of Vol. 2, No. 9, dated May 16, 1837.

According to former Blade reporter John Grigsby's account in The Blade's 1985 anniversary edition, the first inkling of an earlier date came in 1948. The late Dr. Randolph Downes, a history professor at the University of Toledo who was doing research in Michigan at the time, found a reference to The Blade, described as a new newspaper in Toledo, in a Dec. 25, 1835, edition of the Detroit Free Press.

It wasn't until August, 1952, however, when a Pennsylvania woman unearthed the very first Blade published a week earlier than that Free Press report in 1835.

Maxine Shroyer, who had recently started a rare-books business in Pittsburgh, found a copy of The Blade's first edition in a collection of old newspapers she had acquired from one of her first customers. The material was owned by W.B. Herron, a high school physics teacher in Butler, Pa., who had inherited it from an uncle, Samuel F. McCartney, of Mercer, Pa., a retired railroad man who collected books and newspapers as a hobby.

Mrs. Shroyer informed William Block, co-publisher of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and The Blade in 1952, and he purchased the copy.

Tracing roots

It was through this revelatory first copy that The Blade learned of its founders — Mr. Way, an attorney, and Dr. Wilson Everett, both of Urbana, Ohio.

That first edition, according to Mr. Grigsby's account, also described The Blade's motto as “truth without fear,” outlined its editorial course in promising that “a continuous chain of foreign and domestic news will be kept up, that our readers may be advised of the sayings and doings of the great world in which they live,” and told how The Blade's name had been chosen.

Under the editorial “Our Name,” The Blade declared “readers would immediately perceive that the name we have assumed was suggested by the notoriety of a certain city in Old Spain obtained for a peculiar kind of manufacture.”

Blade publisher John Robinson Block met with Conde Agustine, the mayor of Toledo, Spain, in 1997.

Toledo, though not yet incorporated as a city, already had been given a name derived from Spain's historic Toledo, a city famous in part for its manufacturing of swords.

Born during the state of Ohio's land-ownership spat with the Michigan Territory in what became known as the “Toledo War,” The Blade's first editorial told readers they would approve of the newspaper's name “when they are reminded that in the pending contest with Michigan, it has been and will continue to be the duty of the Toledo press to fight with that valour [sic] and ability which the justice of their cause deserves.

“We know there is much temerity in assuming such a name, but we wish to be perfectly understood that we send forth, concealed under it, no menace, and do not threaten to be tart, smart, witty, severe, ironical, caustic, or provoking.

“We assume the name because it contains an apt allusion to the origin of the name of our flourishing place, and to recent occurrences in the border warfare.”

The trailblazing first Blade editorial later reads: “Our blade has no elasticity — it will break before it will bend.”

The Lincoln link

The Blade was linked to President Lincoln through its endorsement of him for president and through their shared belief in the abolishment of slavery in states that had seceded from the union.

But virtually any newspaper that shared The Blade's editorial opinions around the Civil War also shared those same ties to the president. The linking of The Blade and Abraham Lincoln was more personal.

According to James Cornelius, curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Ill., one of the items found in President Lincoln's wallet the night he was assassinated was a letter clipped from a different newspaper that was originally printed by The Blade.

The letter, titled “The Disaffection Among the Southern Soldiers,” was first printed in The Blade on Aug. 22, 1863. The Blade said the letter was “picked up in the streets of Brandon, Miss., by Captain Dennis of the 72nd O.V.I. We have the original in our possession.”

“There are several interesting points in the letter,” The Blade's report said, analyzing the letter and its author. The newspaper's report continued: “but the most notable are the concessions that the South are ‘a defeated, ruined people,' and that the Emancipation policy of the President at which the rebels ‘so long hooted, is the most potent lever of our overthrow,' for he says, ‘It steals upon us unawares [sic], and ere we can do anything the plantations are deserted, families without servants, camps without necessary attendants, women and children in want and misery.'

‘In short,' he most significantly continues, ‘the disadvantages to us now arising from the negroes [sic] are tenfold greater than have been all the advantages derived from earlier in the war.'”

The other bond shared by President Lincoln and The Blade was through legendary former Blade owner and editor, David Ross Locke, known to some as Petroleum V. Nasby.

‘Nasby's Paper'

Mr. Locke already had published numerous Nasby Letters and met President Lincoln on at least three occasions — and President Lincoln was already dead, for that matter — by the time Mr. Locke came to The Blade in the fall of 1865.

Around 1860 or 1861, Mr. Locke, who was the editor of the Bucyrus Journal and would soon join the Hancock Jeffersonian in Findlay, penned the first Nasby Letter — a political satire with words purposefully misspelled to mirror the dialect of presumably fictitious southern white man Petroleum V. Nasby.

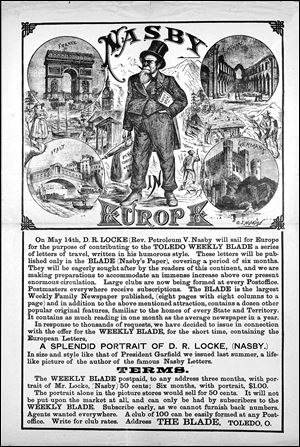

David Ross Locke, former owner and editor of The Blade, wrote a popular column under the pseudonym Petroleum V. Nasby.

The Nasby Letters, printed at first in newspapers in Bucyrus, Findlay, Cincinnati, and throughout the North, became so popular among Union soldiers that, according to author John M. Harrison in 1985, a future official in the Grant administration declared the “crushing of the Rebellion can be credited to three forces: the army, the navy, and the Nasby Letters.”

President Lincoln was so fond of Nasby, according to scholars, that he is said to have read Nasby Letters out loud to his cabinet members, to senators, to guests as 1864 election results poured in, and on the afternoon of his assassination on April 15, 1865.

Nasby Letters found a permanent home with The Blade, or more precisely, the Weekly Blade, when Mr. Locke first came to Toledo.

Mr. Locke, as on-again, off-again editor and owner of The Blade from 1867 until his death in 1888, spearheaded the growth of the Weekly Blade's circulation from 3,000 copies to more than 200,000 during his tenure.

The Blade itself became a daily newspaper in 1848, shortly after telegraph service was installed and maintained a separate weekly edition primarily for farmers and readers in outlying communities that consisted largely of legal notices from city and county offices.

Mr. Locke modernized the Weekly Blade, adding recaps of news, special departments for women and children, hints for farmers and homemakers, editorials, letters from readers, various literary and poetic contributions, and, of course, the Nasby Letters.

The Weekly Blade, a forerunner of today's news magazines, was considered the most widely read publication in the country. It was mailed to subscribers in every state and territory of the union, and was frequently known as “Nasby's Paper.”

The Weekly Blade was discontinued on Oct. 9, 1924, while Mr. Locke's son, Robinson Locke, owned the company. During all but its first 30 years, the newspaper has been owned and operated by two families: the Lockes from 1865 to 1926 and the Blocks from 1926 to the present.

A wide focus

In 1837, George Way, The Blade's first editor, threw the editorial support of the newspaper behind John Berdan to be Toledo's first mayor. Mr. Berdan reportedly won by one vote, and thus began The Blade's role as a major force in the city of Toledo's affairs.

But The Blade's interests are not tethered to the shores of the Maumee River, hence the 1960 change in names from “Toledo Blade” to “The Blade.”

“I think of The Blade as a national institution,” said John Robinson Block, current publisher and editor-in-chief of The Blade and the Post-Gazette in Pittsburgh.

It was Mr. Block's father, former co-publisher of The Blade and Post-Gazette Paul Block, Jr., who changed the newspaper's name prior to The Blade's 125th anniversary celebration. According to the author Mr. Harrison, Paul Block, Jr., made the change, in part, because “while Toledo remained the single most important concern of the newspaper, its interests were wide-ranging.”

Paul Block, Jr., also changed the paper's name because, Mr. Harrison wrote in 1985, he noticed after traveling through Europe that European papers often did not include a city name in their titles.

The Blade long has offered not only editorials and original reporting on events from across Ohio and the United States, but has a history of international reporting dating back at least to Davis Ross Locke's European travels portrayed in some Nasby Letters.

Paul Block, Sr., who bought The Blade from the Lockes in 1926, and his most well-known editor, Grove Patterson, both traveled through Europe and met Italian dictator Benito Mussolini.

Mr. Patterson, who joined the paper in 1910, conducted a regular column called “Way of the World” and became internationally famous for his interviews with world figures in his frequent trips around the globe.

Paul Block, Jr., hired two European correspondents for The Blade, one in 1953 and that reporter's successor in 1956. The Blade's second European correspondent, Fernand Auberjonois, officially retired in 1982 but contributed articles for the paper for years after. Though the correspondents were based in Paris and then London, they traveled throughout the world as, according to Mr. Harrison, “representatives of the smallest American newspaper to maintain its own man in Europe.”

In 1960 alone, The Blade sent Mr. Auberjonois to western Asia, reporters to cover Christian missions in Africa and Asia, and another to join Toledo Zoo officials on safari in South America.

The Blade has continued its global tradition through the years, most recently sending Tom Henry, a staff writer who specializes in environmental reporting, to Greenland in 2009 to report on the devastating ecological effects of global warming.

But it was one international trip taken in 2003 — to Vietnam — that led to perhaps the single biggest boost to The Blade's reputation in its history.

Investigative efforts

Along the same lines of The Blade's international reporting endeavors, the newspaper's investigative reporting efforts date back at least to David Ross Locke.

According to the author Mr. Harrison, in late 1883 and early 1884 Mr. Locke “investigated” the effects Prohibition had in limiting the sale of alcohol in Maine and Vermont. Mr. Locke wanted the law in Ohio that had been in effect in those states for years.

Several decades later, Blade reporter William Brower wrote a series of articles on the status of African-Americans nationally in 1951 — years before the Civil Rights movement's most seminal moments took place.

Locally, The Blade's investigative work on misdeeds by Toledo police officers in 1990 and on the recruitment of athletes at Toledo's Scott and Start high schools in 1995 sent shock waves through the community that reverberated for months.

In 1999, The Blade published a series titled “Deadly Alliance,” an investigative series detailing a pattern of misconduct by the government and the beryllium industry which resulted in deaths and injuries to dozens of workers. “Deadly Alliance” was a Pulitzer Prize finalist the next year.

The newspaper's first and only Pulitzer Prize came on April 5, 2004, when three Blade reporters received journalism's highest honor for uncovering the atrocities of an elite U.S. Army fighting unit in the Vietnam War that killed unarmed civilians — including children — during a seven-month rampage.

The Blade's national reputation was cemented that day.

Blade publisher John Robinson Block, left, celebrates with reporters Mitch Weiss, Michael Sallah, and Joe Mahr and photographer Andy Morrison, right, after The Blade learned it had won the Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting for its 'Buries Secrets, brutal Truths' series on the Vietnam War.

“The Blade is well known in journalistic circles for its enviable record in the Pulitzer Prize competition,” said Sig Gissler, administrator for Pulitzer Prizes at the graduate school of journalism at Columbia University. “Its remarkable commitment to watchdog journalism was reflected in hard-hitting reports that won the Pulitzer for Investigative Reporting in 2004. The paper also was a Pulitzer finalist two other times for work that required deep digging.”

The Blade's other Pulitzer finalist effort — “Coingate,” which uncovered widespread government corruption in Ohio in 2005 and led to numerous criminal convictions — was a 2006 finalist in the Pulitzer's Public Service category, said by Mr. Gissler to be “often considered the most prestigious Pulitzer category because it shows how a news organization uses all of its journalistic resources in pursuit of a good cause.”

Pulitzer Prize

The Blade's Pulitzer-winning “Buried Secrets, Brutal Truths,” about the sins of the elite Army unit Tiger Force during the Vietnam War, began through a relationship between The Blade's then-Washington-based science editor, Michael Woods, and his neighbor, U.S. Army Col. Henry Tufts.

Colonel Tufts was ousted from his job as top Army cop just as the Army's investigation into the Tiger Force atrocities in the 1970s was wrapping up, and when he left his job he took boxes of records with him and stored them in his basement. He asked Mr. Woods to place the records where they'd be part of the public domain after he died, and Mr. Woods gave the records to the University of Michigan's Harlan Hatcher Graduate Library.

Mr. Woods negotiated a six-month head start for The Blade to review the records before they were made public, and then-Blade reporter Michael D. Sallah was assigned to drive from Toledo to Ann Arbor each day to read Colonel Tufts' documents.

Mr. Sallah eventually was paired with then-Blade staffers Mitch Weiss and Joe Mahr, and together they scoured government records, interviewed 43 former Tiger Force members, and went to Vietnam to talk to family members of the victims to detail a pattern of violence by the unit during a seven-month period in 1967.

What the series found was that the highly trained reconnaissance unit killed unarmed civilians, including children, and that Army leadership knew of and in some cases encouraged the unit's actions. The reporters also discovered that the Army failed to prosecute soldiers who killed unarmed civilians after an investigation found the platoon had committed war crimes.

“If The Blade didn't aggressively pursue this story, this monumental event that was buried by the U.S. government never would've surfaced,” said retired Blade vice president and executive editor Ron Royhab. “I think about that frequently. … One of the highlights of my career was to be involved with this project,” said Mr. Royhab, who retired last year.

Above and beyond

The reporters went beyond detailing the violence and showed how the atrocities continued to haunt the veterans nearly 40 years after the killings. Additionally, current Blade photographer Andy Morrison traveled with the reporters to Vietnam to enhance the report with images of the land where the atrocities occurred.

Among the memorable images used for Day 1 of The Blade's series is a picture by Mr. Morrison of a Vietnamese man walking through a rice paddy where his father and other farmers were killed by Tiger Force soldiers decades before.

A dozen Tiger Force members expressed remorse for their actions — nine had been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder by the time The Blade won the Pulitzer — and several described vivid flashbacks or nightmares.

Even though the Army investigated the actions of Tiger Force for 4 years, finding that 18 soldiers committed war crimes ranging from murder and assault to dereliction of duty, the case never reached a military court and no one was ever charged.

“Through hard work and our reporters' zeal to get to the truth, we were able to go to Vietnam and uncover these things our government chose to ignore,” said current Blade executive editor Kurt Franck, who was the newspaper's managing editor when the series ran from Oct. 19 through Oct. 22 in 2003. “For some of the soldiers, it was an opportunity to come clean that they were ordered to kill innocent people at a time when it really wasn't necessary.”

Within hours of publication, news of Tiger Force atrocities in 1967 in the Central Highlands of Vietnam was carried around the world.

The St. Petersburg Times in Russia, the France-based International Herald-Tribune, Colombia's El Mundo, the New Zealand Herald, Le Monde in France, the Globe and Mail in Toronto, the Taipei Times in Taiwan, the Hindustan Times of India, and the China Daily of China all ran The Blade's report. American newspapers such as the Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, San Francisco Chronicle, Miami Herald, and USA Today ran it as well.

And nearly one year to the day after The Blade won the Pulitzer for “Buried Secrets, Brutal Truths,” the newspaper ran a front-page story about a local Republican, the Ohio Bureau of Workers' Compensation, and the investment of $50 million into rare coins.

‘Coingate'

In 1998, the Ohio Bureau of Workers' Compensation gave Tom Noe, a former Toledo rare-coin dealer and Republican Party fund-raiser, an infusion of $25 million to invest in a rare-coin venture.

In the years that followed, Noe emerged as a key player in the Ohio GOP, winning plum appointments to the Ohio Board of Regents and the Ohio Turnpike Commission. Later, the bureau gave him a second $25 million, putting him in charge of a $50 million rare-coin fund.

On April 3, 2005, next to a large headline, picture, and story detailing the death of Pope John Paul II, The Blade raised questions about the rare-coin fund and Noe, eventually triggering “Coingate.” About 20 criminal convictions resulted, including those of Noe for theft and former Ohio Gov. Bob Taft on misdemeanor ethics charges.

Noe is serving 18 years in state prison for stealing millions of dollars from the rare-coin funds. Before beginning his state prison sentence, he had served two years in a federal prison after pleading guilty to using conduits to launder $45,400 in illegal contributions to President Bush's 2004 re-election bid.

The so-called “Coingate” scandal, which shook the Republican Party in Ohio, played a major role in Democrats sweeping to power in the state in 2006 and marked an astonishing period of national acclaim and success for a midsize daily newspaper like The Blade.

“A lot of papers double our size wish they could get a nibble at uncovering stories of this magnitude,” Mr. Franck said. “I don't think there are many papers that would be as aggressive in putting as many feet on the ground to do the work that we did.”

Noe exposed

At its peak, The Blade's investigation into Noe and the BWC's investment included six reporters, an editor, a forensic accountant, and a file clerk. Over about 19 months, the project grew into a wide-ranging examination of influence-peddling and corruption in state government.

Initially, The Blade was criticized for its investigative reporting of Noe. Some readers canceled subscriptions, some local business leaders refused to speak with The Blade, and then-Governor Taft came to Noe's defense.

In early May, 2005, The Blade had exposed that Noe had given millions in state funds to a coin dealer who had done time in a federal penitentiary. With pressure mounting, Noe resigned his appointments to the Ohio Turnpike Commission and Ohio Board of Regents, and the bureau announced plans to dissolve the coin fund.

State officials, though, trod lightly with Noe, careful not to imply he had engaged in any wrongdoing with the coin funds. That all changed on May 26, 2005, when attorneys for Noe acknowledged that up to $13 million might be missing from the coin funds.

“Coingate” was born as more than a dozen criminal and civil investigations ensued. A task force and grand juries were assembled, and politicians quickly distanced themselves from their onetime friend and prolific fund-raiser.

In November, 2006, during closing arguments in the Noe coin-fund case, then-Lucas County Assistant Prosecutor Larry Kiroff addressed an issue first raised by Noe's attorneys. They had suggested that investigators only began looking into Noe's behavior after The Blade began writing stories, insinuating that they were trying to curry favor with the paper.

But Mr. Kiroff told the jury the suggestion was ludicrous and thanked the newspaper for bringing the issue to light.

“Good for the Toledo Blade,” he said. “Call them watchdogs.”

Marching on

Mr. Franck, The Blade's executive editor, said “The Blade's DNA is investigative reporting.”

“It was that way before I got here [in 2000] and it needs to continue to be that way as we move forward. We've got to do the nuts-and-bolts stuff, and we'll continue to do that, but investigative reporting is where we've made our mark.”

The motivation behind the paper's investigative work is not prizes, but service to readers, said Dave Murray, The Blade's managing editor. Mr. Murray was the supervising editor of the three series that were named Pulitzer finalists, including “Buried Secrets, Brutal Truths,” which won the Pulitzer prize for investigative reporting in 2004.

“The daily newspaper in so many communities is the only institution capable and willing to take on powerful interests, whether they be government or corporations, and expose wrongdoing and harm to the public,” Mr. Murray said. “Our readers count on us to do that and I'm proud that The Blade has been there for them.”

The Blade remains committed not only to investigative and beat reporting for its daily print product, but for its evolving multimedia presentation on the Internet.

The newspaper's Web site, toledoblade.com, reaches about 50,000 unique visitors each day, generating about 200,000 page views. Included on the site are breaking news reports, videos, blogs, and other tools that are revolutionizing the news business.

“We're going to be serving people with new technologies, some not yet fully developed,” said John Robinson Block, The Blade's publisher and editor-in-chief. “We're in the journalism business, and that means reporting and disseminating news. Obviously, we'll be a multimedia platform. We are already, to some extent, but we will be more and more.”

Myriad epitaphs have been written already for the newspaper industry, even though the industry continues to print newspapers and publish Web articles daily. The business is not without its financial concerns, to be sure. A dip in overall advertising, declining circulation because of a shift in readership online, and struggling American housing and automotive industries have all hurt newspapers' bottom lines.

The Blade is by no means immune from those hardships and from a struggling economy in northwest Ohio and southeast Michigan — as evidenced by the cuts in daily page counts, the size of the pages themselves, and reductions in staff, among other things.

A contentious contract negotiation between the paper and its labor unions plagued The Blade in 2006 and into 2007, during which the newspaper locked out some of its union workers, and The Blade's unions led a public boycott of the newspaper itself. The Blade's management and labor leaders are currently meeting to negotiate a new contract amid hard times for working families and businesses alike.

The Blade is owned and operated by Block Communications Inc., whose executive committee comprises, from left, John Robinson Block, Karen Johnese, Allan Block, Diana Block, and William Block Jr. (not pictured).

While there are undoubtedly issues for The Blade to resolve in the present, the paper continues to have an eye on its future. In development for launch in early 2011 is an online version of the newspaper's daily printed product called The Blade's e-edition. For a small fee, online readers will be able to view articles in the same format they get from their daily paper — with multiple articles on the same Web page.

Joseph H. Zerbey IV, president and general manager of The Blade, said three of the newspaper's major advertisers already have committed six-figure dollar amounts toward e-edition advertising, with a significant portion of that money being separate from what those companies pledged in print advertising.

Mr. Zerbey said the combination of The Blade's print circulation and online readership gives it the highest media market penetration (80 percent of households) of any newspaper in Ohio.

While Mr. Zerbey does not believe the printed newspaper will disappear any time soon, he is excited about the steps The Blade is taking to evolve in a changing industry.

“In terms of the institution of The Blade, the only people who can kill it are us,” Mr. Zerbey said. “As long as we maintain good, solid local news coverage, we're going to be fine.”

Here's to 175 more birthdays.

Information from John M. Harrison's 1985 book, “The Blade of Toledo: The First 150 Years,” as well as from numerous previously published articles by The Blade, was used in this report of the newspaper's 175-year history.

Contact Joe Vardon at

jvardon@theblade.com

or 419-724-6559.