Local families struggle under welfare rules

State, facing $130M federal fine, trims numbers of recipients

4/22/2012

The Blade

Buy This Image

Victoria Bernal and sons Justice, 5, in her lap, and Jace, 2, wait their turn at the Providence Center food pantry in South Toledo. They get by on child support, $328 a month in food stamps, and the occasional odd job, Ms. Bernal said.

Amy Lingo and her 3-year-old son Jesse live a threadbare existence in a mobile home park in West Toledo -- no cell phone, no cable television, no "extras," she said.

But soon, she could lose one of her few lifelines -- $368 a month in cash assistance.

Ms. Lingo and thousands of others like her are at the center of Ohio's struggle to avoid a looming $130 million federal welfare penalty.

Amy Lingo, outside her Toledo home with son Jesse, 3, is in danger of losing her assistance. Ms. Lingo failed to meet work requirements after knee surgery. Her case is being reviewed.

The number of Ohioans receiving welfare has dropped by more than 26 percent -- more than 62,000 people -- since the beginning of last year to levels not seen since October, 2007, before the onset of the recession.

But advocates for the poor say those leaving the welfare rolls aren't finding steady jobs and are being booted off by county assistance offices and a state agency racing to avoid the fine.

As of March, 172,836 Ohioans were receiving welfare, compared with 235,143 at the beginning of 2011.

Ms. Lingo was notified in January that she would be losing the monthly assistance she depends on to pay her rent and utility bills. The reason for her sanction? Failure to meet the weekly work requirement most welfare recipients must fulfill.

But Ms. Lingo, who suffers from severe arthritis in both knees and who recently underwent knee-replacement surgery, thought her caseworker understood that she was temporarily unable to do physically demanding work.

Panicked, she called Advocates for Basic Legal Equality, which assists low-income people with legal issues. With the help of an ABLE lawyer, she has been able to keep her benefits while her case is examined.

Ohio is facing a federal fine because not enough welfare recipients are participating in 30 hours weekly of "work activities." Ohio has failed to meet this goal every year since 2007; fines have been levied annually since by the federal government but will soon start coming due if the state is not in compliance by September.

The potential fine would be huge -- Ohio receives $728 million in federal funds annually to run the program, said Ben Johnson, spokesman for the state's Department of Job and Family Services.

The system

To qualify for welfare, formally known as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or Ohio Works First, a family of three cannot make more than $795 a month, or 50 percent of the federal poverty level. The time limit for most families is 36 months, shorter than the five-year limit imposed by the federal government through welfare reform in 1996.

"Ultimately, the goal is to give [recipients] the skills to be self-sufficient. For most people, cash assistance is only available for three years," Mr. Johnson said. "It's not available for anyone forever."

Adults receiving assistance must participate in "work activities" -- usually 30 hours a week at a nonprofit-organization or community-service job. In some cases it can include education or training. They do not receive payment for the job other than their benefits, which for a family of three is $450 monthly.

When adults don't meet their work requirement, they can be sanctioned and removed from the program. In January, 2011, 26 percent of the state caseload was meeting its work requirements; by January, 2012, that number had risen to 39 percent.

Because of the pressure to change the program's statistics, are counties just throwing off families in need of assistance?

Jack Frech thinks so.

"It is now all focused on making sure these folks get out there and do these work requirements," said Mr. Frech, director of Job and Family Services in southeast Ohio's Athens County. "We're not equally committed to making sure they eat every day."

The state disagrees.

"We're not out to sanction anyone," Mr. Johnson said. "We're not looking to throw people off the program. But this is federal law."

Reasons for removal

The leading reason recipients leave the program in Ohio is sanctions; however, that represents only about 36 percent of the people who leave, Mr. Johnson said. Other reasons for removal from the program include failure to "follow paperwork," time limits, income increases, or a change in family status such as a minor child turning 18.

Deb Ortiz-Flores, executive director of Lucas County's Department of Job and Family Services, disputes the idea that people are being unfairly tossed from the welfare rolls, although she said Ohio's counties are aggressively using every tool they have to bring their work participation numbers into compliance.

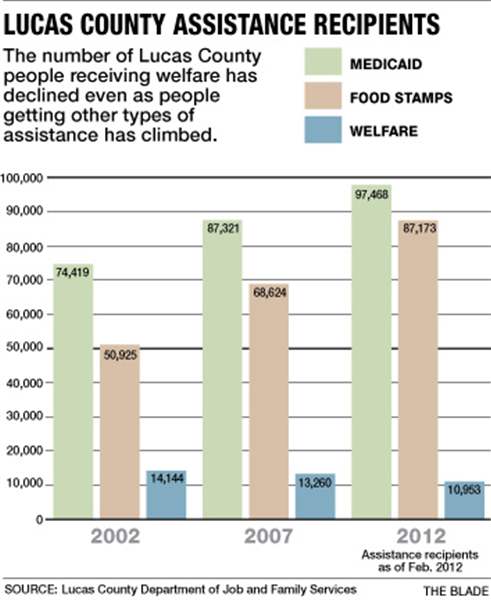

In Lucas County, the number of welfare recipients has declined, even as the number of people in need of food and medical assistance has climbed in recent years.

As of March, Lucas County had 97,863 Medicaid recipients, 99,746 food-stamp recipients, and 10,571 welfare recipients.

That compares with 74,419 Medicaid recipients, 50,925 food-stamp recipients, and 14,144 welfare recipients in 2002.

Ms. Ortiz-Flores said agencies such as hers have struggled with the loss of $170 million in funds statewide to aid clients who need transportation assistance or other support to help them keep a job and stay off public assistance.

In 2007, Lucas County Job and Family Services had more than $2 million to assist low-income employed clients with costs such as car repairs, GED classes, and uniforms or tools for work.

In 2012, the agency is projected to have $60,000 for these same expenses.

"Those dollars helped us move people off cash assistance quicker and helped people from needing cash assistance," Ms. Ortiz-Flores said.

Randy Cochrane, Job and Family Services director in eastern Ohio's Muskingum County, where more than 50 percent of its aid recipients are meeting their work requirements, said welfare "is not a cash assistance program. This is a work program. … If you don't work those hours, you will get sanctioned."

Welfare rolls have fallen in Muskingum County in the last year, despite a high unemployment rate there -- 12.2 percent in February.

Mr. Cochrane said he understands why some people might have concerns about the sanctions but added, "This is a federal law. If we receive a federal [fine], the entire system is going to be impacted."

Waiting for help

On a recent Thursday morning, well over a dozen people were already waiting for the food pantry at Providence Center to open.

The South Toledo pantry doesn't start serving until 12:30 p.m., but it takes only the first 25 people, so folks tend to get there early to secure a spot.

Jack Frech, director of Job and Family Services in Athens County, is a prominent critic of welfare reform.

Among those waiting was Victoria Bernal, with her two sons, Justice, 5, and Jace, 2. Justice played with a blue stuffed monkey and sat in his mother's lap. Ms. Bernal, 36, has used up her three years of welfare benefits and no longer receives cash assistance. She and her children get by on child support, $328 a month in food stamps, and the occasional odd job, she said.

"I'm looking for work. It's just not that easy," she said.

Eugene King, director of the Ohio Poverty Law Center in Columbus, a group that advocates for policies that benefit low-income people, said Ohio's three-year limit on benefits -- enacted by the state legislature in the 1990s -- is hurting its most vulnerable residents as well as its own economy.

"Ohio has arbitrarily opted for a three-year time limit; the federal limit is five years," Mr. King said. "In light of the ongoing recession, Ohio should revise its limits so that people can receive the full five years of benefits."

Also in line for food from the pantry was Taschae Carter and her aunt Linda Carter, who didn't mince words.

"We need food, or we wouldn't be here," she said.

Taschae Carter, 23, who has five children, has exhausted her three-year benefit limit. She has no income and said she depends on family assistance.

"It is hard. It is embarrassing," she said.

Effects of reform

Research from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities has shown that welfare reform seriously weakened the safety-net aspect of welfare, as Ms. Bernal and Ms. Carter have experienced. In 2010, the temporary assistance program served only 27 of every 100 families in poverty, down from the cash assistance that welfare provided to 68 of every 100 families in poverty prior to 1996.

Additionally, the national caseload rose by just 13 percent during the recession, even though the number of unemployed people doubled, and welfare caseloads in 22 states rose little or not at all. In contrast, the national food-stamp caseload rose by 45 percent, according to research by LaDonna Pavetti, vice president for family income support at the center.

And when women lose their welfare benefits, their children are hurt as well. Childhood poverty can have a long-lasting impact.

"Income in children's early life not only affects their learning in school but their earning in later life," Ms. Pavetti said. "It has not only short-term consequences for kids, but long-term consequences."

Linda Carter, waiting at the Providence Center, doesn’t mince words: ‘We need food, or we wouldn’t be here.’

If a family has exhausted the 36 months of benefits and still needs help, it can apply for an extension. However, the criteria and policies for those who qualify for an extension differ from one county to another. And in some counties, getting an extension seems to be nearly impossible; many Ohio counties last year granted no so-called "hardship" extensions. Others granted a handful.

One notable exception is Athens County, in Ohio's Appalachian region. "Our perspective is the purpose of the [assistance] program is to take care of families first. Everything else comes second," said Mr. Frech of Athens County, one of the state's most impoverished counties.

Mr. Frech is a prominent critic of welfare reform, Ohio's three-year time limit, low benefit levels, and county-by-county system of exemptions.

The monthly benefit payment -- $450 for a family of three -- is not nearly enough for a family to live on, especially given the cost of maintaining a car and auto insurance, a necessity for welfare recipients in a rural county trying to comply with work requirements, Mr. Frech said.

Seeking shelter

Virtually all of the women Jeanelle Addie sees at La Posada, a South Toledo shelter, have exhausted their three years of cash assistance or have been removed from the program.

"I understand that there's been generations of families on the system, and they are trying to end that. …

"But they need to give [people] some assistance, some transition," said Ms. Addie, residential manager at the shelter, which is a last, desperate bulwark against homelessness for many women and their children.

Akinya Washington, who is staying at the shelter with one of her three children, said she lost her assistance after missing a job-skills class when her infant daughter Ja'shayla was hospitalized.

"They sanctioned me," she said. "But I was not going to leave my daughter in the hospital just to go to a class for a $500 check. … This was my daughter's life."

She has been able to get by on food stamps, assistance from family, and work from a temp agency.

Another shelter resident, Chiquita Dale, who is nine months pregnant and has two other children, lost her cash assistance after missing job-search classes. She said she missed the classes because she had to flee from a violent relationship.

"I was being physically harmed. I got myself out of that situation," she said.

Counties can give work requirement exemptions to women seeking to leave domestic violence; Ms. Dale said she was unaware of this.

By the time most women get to the shelter, they have no income whatsoever, Ms. Addie said.

"I can't even buy my son a toothbrush," lamented Barbara Parraz, another La Posada resident.

Defending the system

Despite the system's problems, the assistance program's time limits and work requirements are still better than the welfare system that preceded it, said Joel Potts, executive director of the Ohio Job and Family Services Directors' Association. Mr. Potts helped implement welfare reform at the state level during the 1990s. Caseloads have fallen tremendously since that time. In March, 1992, the state's welfare caseload hit its peak of 748,717 recipients.

In the current system, there are clear expectations that adults who can work should work, and generational welfare has essentially ended. The state also has been able to invest more in work supports such as child care, Mr. Potts said.

"I do think the public has a very clear expectation of what we need to be doing," Mr. Potts said, adding that welfare should serve as a temporary assistance and not a way of life.

However, many of the families who remain on assistance do face serious challenges, he said, such as a lack of basic education, mental-health disorders, or other obstacles to working.

"We are left with a smaller population, but they are a much more difficult population to work with," he said.

Contact Kate Giammarise at: kgiammarise@theblade.com or 419-724-6091.