EDUCATION MATTERS

Cincinnati offers Toledo schools a road map to success

District turned around low-performing schools

5/13/2012

Seventh grader Deontez Powell assists with distributing bags of free food for students to take home on a bus outside Roll Hill Elementary School in Cincinnati.

the blade/nolan rosenkrans

Buy This Image

Seventh grader Deontez Powell assists with distributing bags of free food for students to take home on a bus outside Roll Hill Elementary School in Cincinnati.

CINCINNATI -- Deontez Powell hurried with the bag, stuffing it onto the bus before another one flew toward him.

The Roll Hill Elementary seventh-grader had to be quick because the bags -- stuffed with free food for students to take home over the weekend -- needed to be dropped off before the frenzy started.

The food comes from Blessings in a Backpack, a national nonprofit organization that sends food home with students on the weekends. Toledo too sometimes sends food home in backpacks. Roll Hill does it every week.

Shelly Mokas, who coordinates with community groups at the school, directed a team of students and Roll Hill staff members as they wheeled around a cart of bags filled with food. "These are my helpers," she said. "I couldn't do it without them."

Deontez and the crew hadn't quite filled the line of buses waiting outside the school when Roll Hill seemed to empty all at once. It's not normally this chaotic, Principal Vickie Graves-Hill insisted. A perfect storm of near-end-of-the-day activities left the school in a Friday frenzy, hundreds of students milling about the sidewalk, in the parking lot, in doorways, and on buses.

Inside, students signed in at the Boys and Girls Club housed at the school. Staff and volunteers provided milk; some students ate while others did homework, required before they could use the club's more fun areas.

These are the scenes that make Toledo Public Schools officials smile and grow slightly envious.

To see things like these, and to ask "How?" and "Can we do this too?" is why they traveled to Cincinnati recently. Julie Doppler, coordinator for community learning centers in Cincinnati, said the partners that the district's community program brings into schools are invaluable.

"The dollars this leverages," she said, "is remarkable."

RELATED ARTICLES: Education Matters -- The Transformation of Toledo Public Schools

Jim Gault, left, TPS' chief academic officer, and James Gant, TPS business officer, chat with Mary Ronan, Cincinnati Public Schools superintendent, during a visit by TPS officials and employees to the Cincinnati district last month.

The parallels between what happens at Roll Hill when school lets out and what TPS plans at its still-in-formation United Way partnership "schools as community hubs" are striking. A Boys and Girls club is housed in Roll Hill, and a lead community-services organizer helps keep children in the building until 7 p.m., keep them fed, and organize mental health services, pediatrician visits, tutoring, and more, free of charge to students.

Although both school districts may have developed community-school programing, more striking than the similarities is how much further ahead Cincinnati is than Toledo. This year, TPS initiated four community hubs, and none is fully up and running. Cincinnati has more than 30 hubs, with 600 partner agencies working in the schools.

And that, in a nutshell, is the tale of these two cities, at least in a public-education sense. The Glass City is in the midst of a reform effort that aims to, in the simplest terms, boost test scores.

The Queen City's been there, done that, and is moving on to the next challenge.

The Blade has profiled in the past year Toledo Public Schools' reform attempts and compared those with efforts in similar communities in other parts of the country. But maybe the best model -- if not for holistic transformation, at least immediate, significant change -- lies only a few hours south on I-75.

Unlike the city's gun violence-reduction program profiled last week in The Blade, TPS hasn't drawn direct inspiration for its reforms from Cincinnati, but there's evidence that perhaps it should.

Effective rating

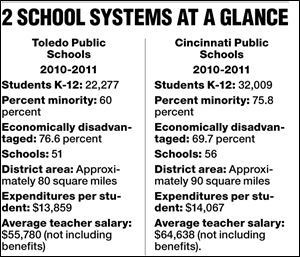

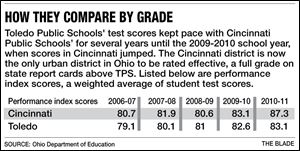

Cincinnati is the only urban district in the state rated effective, thanks to recent improvement in test scores that Toledo envies. Value-added scores -- an increasingly popular, if disputed, metric of the impact of teachers on student growth -- show that Cincinnati Public students grew more rapidly academically than their Toledo peers. Numerous programs that Toledo wants or is developing were implemented in Cincinnati years ago.

Make no mistake, the Cincinnati Public Schools district has problems. Its graduation rate is unacceptably low, and test scores still don't compete with suburban districts' results. But for an urban district, it has made real progress.

What Cincinnati accomplished gives TPS hope that its transformation plan will be the spark that gets real academic improvement started.

"That is exactly where we are started," Jim Gault, TPS chief academic officer said. "It gives us verification and justification for what we are doing."

Although deep differences between the two cities makes an apples-to-apples comparison unfair, what seems most apparent is that the Queen City managed its turnaround because of two things: a willingness to think big and the effective leveraging of one-time federal stimulus funding to pursue an intensive, focused improvement effort at its worst-performing schools.

Taking action

TPS officials won't dispute their aspirations toward a Cincinnatilike standing -- they've seen the test scores. A crew of administrators -- accompanied by teachers' union President Kevin Dalton -- journeyed south last month for a two-day "how did you do that?" session with Cincinnati Public staff and invited a Blade reporter along.

The Cincinnati schools use numerous programs and practices that could yield dividends, but the biggest may be lessons learned about how Cincinnati used its federal stimulus dollars in 2009.

When Cincinnati got millions in short-term funding, it seized the opportunity. The district took 16 of its lowest-performing schools, all in academic emergency -- the equivalent of an F grade -- and built its Elementary Initiative.

Four were totally remade, with new principals and new staff, much as TPS did with Robinson Elementary this year. The rest were given a strict plan of action for improvement.

All received intensive training for teachers and principals. Whole-group instruction was limited, small-group work was emphasized.

A structured schedule for instruction was set up for each school: 90 minutes on math, 90 minutes on reading, 45 minutes on science, and 45 minutes on social studies.

Time audits were done to ensure each minute was used in instruction.

Too often, administrators found, 90 minutes for reading was cut into by lengthy classroom rest room breaks, time settling unruly students, taking attendance, and myriad other minor tasks. Under the Elementary Initiative plan, 90 minutes means 90 minutes.

Each school now has a "fifth quarter," extending the school year by four weeks.

The full-day program is a half day of regular instruction by teachers and a half day of enrichment activities paid for and provided by the organizations in the community-learning centers.

Two-person teams of a reading and a math expert were assigned to schools, made regular visits, and gave in-class support and critiques so that teaching could improve throughout the year. Schools were accountable to coaches, coaches accountable to district administrators.

Those changes didn't occur without battles. Deputy Superintendent Laura Mitchell, who headed the initiative, said teachers filed grievances numerous times during the first year. She carried on with the reforms.

"These schools were in academic emergency," she said. "If they knew what to do, they would have done it."

That year, 13 out of 16 increased their test scores, and seven moved into continuous improvement. Only one of the original 16 remains in academic emergency.

The grievances stopped, she said.

Education Matters: A look at the series

The districts profiled by The Blade in the Education Matters series that may hold lessons for Toledo Public Schools are from different regions of the country and operate in many different ways.

But there's at least one similarity in all three districts: Each has a strong partnership with a private institution that offers training and support for teachers and administrators.

Chattanooga has the Benwood Foundation and the Public Education Foundation, which provided both funding and hands-on help. Syracuse has Say Yes to Education, a national nonprofit that gave grants, lobbied for public and private funds, developed turnaround programs and community initiatives, and helped with training.

In Cincinnati, housed in a separate section of the Cincinnati Public Schools' district administration building, is the Mayerson Academy, a private school resource center that provides training and support for teachers. Although the academy works with other districts, its focus is on CPS, and the two work intricately together.

Toledo has to contract with companies states away to get expert training; Cincinnati's is right next door.

TPS reaction

Ms. Mitchell greatly impressed TPS administrators, less so Mr. Dalton, who later said that many of those grievances she described weren't so much from teachers who hated change but from teachers who were given more accountability and responsibility but not more time for the paperwork and preparation that went into it.

"There's a difference between being told to do something," he said, "and being brought in and given the proper supports."

But there were programs in Cincinnati for which he shared enthusiasm with Mr. Gault.

The use of technology and data for tracking students there is what Toledo wants to emulate. And school improvement coaches could help in Toledo, he said, as long as the coaches have teaching backgrounds so they know what they're looking for.

When Toledo got its stimulus funding, the district hired interventionists and staff to reduce class sizes.

The hires were helpful at the time, but once funding ran out in two years, TPS had to eliminate the positions, with little to show for the money spent.

As one TPS official put it, when stimulus dollars came, "[Cincinnati] changed their district. We hired staff."

That money isn't coming back, but some policy changes, if made, could free up funds in Toledo. Although TPS pays teachers much of its Title I dollars each year for required training, Cincinnati doesn't.

That frees up funds for "fifth quarters," community resource coordinators, preschool programs, and turnaround effort.

Assistant principals were added to give principals time to conduct training. And of the about $20 million TPS gets in Title I funding each year, much is tied up for staff members who are added to reduce class sizes, much as stimulus funds were.

Comparisons

At times, it can seem a comparison between Toledo and Cincinnati is unfair. Both cities are roughly the same size, by both physical space and population. But Cincinnati boasts a network of surrounding suburbs that dwarfs Toledo's: Cincinnati's urban population is about 1.5 million, Toledo's is less than a third of that.

That size -- along with its status as headquarters for companies such as Procter & Gamble, Kroger Co., and Macy's Inc. -- means money. Private collaborations like Cincinnati's -- and the funding that comes with them -- seem unlikely in Toledo. Even the district headquarters seemed more up to date than Toledo's, with an auditorium for board room meetings that makes TPS' seem antiquated.

"This is unreal," Mr. Gault said under his breath as he walked into the auditorium.

Some core elements of Cincinnati Public Schools may be difficult to replicate elsewhere. The district's 14 high schools are all choice schools -- students aren't assigned to a neighborhood school. The school system gives high school students Metro transit passes, and they go to the schools they choose. Most schools have a distinctive theme, such as performing arts or design technology.

But not everything is easy going in Cincinnati. It faces the same fiscal restraints as Toledo. Employees took pay freezes and increases in medical-coverage costs; layoffs are needed to offset a huge budget deficit. Levies are still difficult to pass.

"These days, you're not even sure about renewal [levies]," Superintendent Mary Ronan said, although being an effective-rated district, she said, helps.

Toledo Public Schools has made reforms and started many of the programs Cincinnati did.

It is working with the United Way building community hubs, beefing up academics at its central city schools, and started turnaround programs at some buildings.

But much of it is piecemeal, and TPS administrators say they need years to implement a full transformation.

Cincinnati showed a district can make major progress in a year.

Toledo Public Schools took a step. The question is: Can it take a leap?

Contact Nolan Rosenkrans at: nrosenkrans@theblade.com or 419-724-6086.