LEGACY PROJECT OF NORTHWEST OHIO

8 African-Americans recognized during group’s annual luncheon

10/7/2012

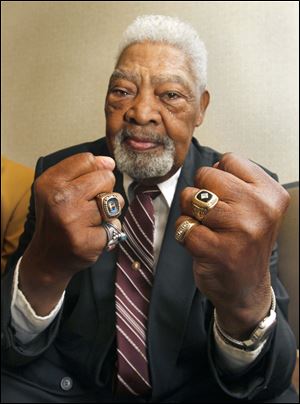

Emerson Cole shows off his Hall of Fame University of Toledo ring on the left hand, and his World Champion Cleveland Browns ring on the right.

On his left hand, Emerson Cole wore an object Saturday that many consider to be an urban legend, or at least something fans have spent decades dreaming about: a Cleveland Browns championship ring.

Mr. Cole, who was honored during the African American Legacy Project of Northwest Ohio legends luncheon Saturday, was a member of the Browns’ 1950 National Football League champion football team.

It was 5 degrees below zero, Mr. Cole, 84, recalled on Saturday about that game.

“I didn't feel anything from below the belt,” he said of the Browns' 30-28 victory over the Los Angeles Rams.

Seven others were also named as honorees this year: Clara Hodge Brank, State Sen. Edna Brown, George Davis, Jr., Lancelot C.A. Thompson, Cenia Willis, Ernest Jones, Sr., and Alvin Stephens, Sr.

Mr. Jones died in 2010, Mr. Stephens in 2000.

The annual event, held this year at the Hilton Garden Inn in Perrysburg, is “significant because we're rediscovering untold stories and retelling them,” said Robert Smith, president of the African American Legacy Project of Northwest Ohio.

Mr. Cole was presented with a Kente stole — a hand-woven ceremonial cloth — by his son Charles Cole of Columbus.

Mr. Cole, a 1946 graduate of Swanton High School, received an athletic scholarship to the University of Toledo, from which he received a bachelor of arts degree in education in 1964.

In 1950, he became the first black man to be drafted by the Cleveland Browns. Although other blacks were on the team at the time, Mr. Cole said, they had been acquired by the team through trades. The Rams had integrated the NFL in 1946.

“Paul Brown, his first statement every year was, ‘If you can't play with the colored players, you can go to the office and get your ticket home,’ ” Mr. Cole recalled.

During his time with the team he was a linebacker on defense, and a fullback or halfback on offense, and played on kickoffs and punts, too.

“If you couldn’t play five positions, you didn’t have a career,” he said. “That was big fun. … It was a very harsh existence because they hit hard out there,” Mr. Cole said of his three seasons with the Browns. He smiled slyly and added, “I gave out more concussions than I got.”

After a fourth season of football — spent with the Chicago Bears — Mr. Cole opted to leave the National Football League and join the Lucas County Sheriff's Office as a deputy in January, 1953.

He had a buddy, he said, who owed him a favor, so Mr. Cole asked to be hired onto the department.

“I liked law enforcement,” he said.

His career with the sheriff's office lasted only six years.

“It was dangerous,” he said. As a black deputy, he had to worry not only about criminals on the street but also about racist deputies in his own department.

“It was because of the times, really,” he said.

He recalled taking the test to be promoted to sergeant, in which he finished first and was promoted to the detective bureau.

When he asked to take another exam for a second promotion, he was told he would never achieve a higher rank.

In 1959, he left the department and went on to do community work.

His proudest achievement, he said, was working for an Ohio Civil Rights Commission branch in Erie and Huron counties that found jobs for “thousands” of people and led to investigations in “hundreds” of factories.

Mr. Cole has been inducted into the Swanton High School Hall of Fame and the University of Toledo Hall of Fame.

Contact Taylor Dungjen at: tdungjen@theblade.com or 419-724-6054 or on Twitter @tdungjen_Blade.