FIGHTING IRISH BATTLE AGAINST WOLVERINES IN TOLEDO

Notre Dame made its mark in game on downtown field that ended in 23-0 loss to mighty Michigan

12/31/2012

The Blade's headline for the 1902 story on the big game notes the lower-than-expected turnout.

THE BLADE/JEREMY WADSWORTH

Buy This Image

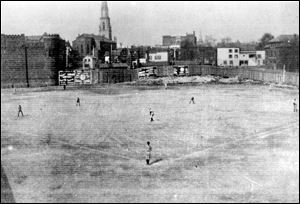

St. Mary's Roman Catholic Church stood in the background of the Armory Park baseball field, where the Notre Dame-University of Michigan game was played 110 years ago.

The echoes awaken on the intersection of Spielbusch Avenue and Orange Street in downtown Toledo, behind the old stone-faced courthouse and on the grassy campus of the Civic Center Mall.

There is no mention that this spot downtown is a portal to football history, and perhaps that is fitting. Why should a game played on a raw, gray day 110 years ago before a crowd of 1,700 be remembered?

But of all places, this ground is where a little-known Indiana university that would become the most famous brand in college athletics played one of its most important games.

Before the Gipper, Rockne, and the Four Horsemen, there was the contest between Notre Dame and the University of Michigan that jump-started the myth.

The neutral-site meeting at Armory Park on the afternoon of Oct. 18, 1902, in downtown Toledo was not supposed to be a game at all.

Michigan at the time was the standard of college football empires, its “Point-a-Minute” teams under Fielding Yost winning national titles in 1901 through 1904. The Wolverines’ train ride to Toledo was sandwiched by a 119-0 victory over Michigan State and an 86-0 dusting of Ohio State — part of a five-year dynasty in which they outscored opponents 2,821 to 42.

Their Catholic challenger, meanwhile, still clawed for relevance and acceptance. It was only 15 years earlier that Michigan had literally taught Notre Dame how to play football, spreading the gospel of the vicious East Coast game to South Bend, then an industrial town of about 20,000.

Denied access to the Western Conference — a forerunner to the Big Ten — Notre Dame’s recent schedules included a clutter of high school, club, and college teams with imposing names such as the Illinois Cycling Club and Chicago Dentistry.

The crowd in Toledo expected the worst as they gathered around the roped-off field adjacent to the three-story brick Armory Building. Conservative projections, as Notre Dame halfback Louis Salmon told The Blade, called “for Michigan to defeat us by a score of 60 to 0.”

What happened instead, historians say, continues to resonate today.

When top-ranked Notre Dame attempts to win its 12th national championship against Alabama on Jan. 7 in Miami, consider this:

“That game in 1902,” said Michael R. Steele, author of the Notre Dame Football Encyclopedia, “was a launching pad.”

The last game in Toledo between two teams from the top level of modern college football — the six power conferences and Notre Dame — not only incensed Yost, poured fuel onto a simmering feud, and matched the player many once called the greatest of all time against the Fighting Irish’s first All-American. It also — just maybe — heralded the birth of modern Notre Dame football.

“Our plucky lads put up the grandest and most magnificent struggle that has ever taken place on any gridiron in the West,” wrote the Scholastic, the Notre Dame student newspaper, recounting the game. “The memory of their glorious achievement shall live as long as the Gold and Blue floats across the gridiron at Notre Dame.”

The Blade's headline for the 1902 story on the big game notes the lower-than-expected turnout.

The Blade’s report on the contest was more straightforward, calling it “one of the fiercest games ever played in Ohio.”

“The showing made by Notre Dame Saturday was a surprise to the Michigan players and to Coach Yost. He had not anticipated as hard a game as the battle proved to be. Michigan may be as strong as she was last year, but it would be a difficult matter to convince some of those present Saturday of that fact,” The Blade wrote. “Time and again Salmon, the brilliant fullback of the Notre Dame team, plunged through the tackles for long gains.”

And to think: All this fuss over a 23-0 Notre Dame loss.

Unlikely venue

Toledo seemed an unlikely interloper that Saturday, the identity of this fast-growing manufacturing city more entwined with the nation’s pastime.

Baseball had existed in various incarnations here since 1883, including for two seasons at the sport’s top level in the American Association — a new challenger to the National League. Among those who wore the local threads were Moses Fleetwood Walker, a Michigan graduate who as a catcher for the Toledo Blue Stockings in 1884 became the first black major league player, and Hall of Fame pitcher Addie Joss.

By 1902, a couple thousand fans regularly turned out for the Mud Hens at Armory Park, a bandbox built five years earlier where the fortresslike armory doubled as the left-field wall less than 300 feet from home plate and the steeple of St. Mary’s Catholic Church at Michigan and Cherry towered twice as high just to the right. In June, about 3,000 spectators paid $1.25 a ticket to watch a Michigan-Cornell baseball game there, according to John Kryk’s 1994 book Natural Enemies: Major College Football’s Oldest, Fiercest Rivalry — Michigan vs. Notre Dame.

The box-office success convinced local Michigan boosters — and, ultimately, athletic director Charles Baird — that a UM football game in Toledo would also be good business, although that seemed a stretch. Football was not for everyone. Before the forward pass was legalized in 1906, a wave of player deaths threatened to sentence the sport to the same barbaric dustbin as ancient gladiatorial combat.

President Theodore Roosevelt called for football to “change its rules or be abolished” after the Chicago Tribune reported 18 players — at all levels — died during the 1905 season. The primitive game Toledo fans would witness featured players in scant equipment — leather helmets and quilt-padded uniforms — locked in brain-rattling mass formations.

Still, the game’s popularity was growing, and Michigan expected its empire would draw well on the road.

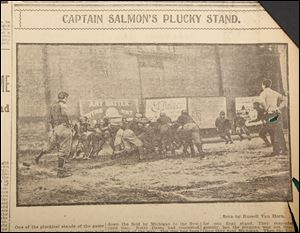

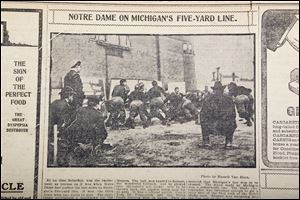

The two teams, in leather helmets and quilt-padded uniforms, face off on Oct. 18, 1902, in the mud at Spielbusch Avenue and Orange Street, now the site of the federal courthouse in downtown Toledo.

UM was champion of the West and everywhere else. Yost, a brash 31-year-old West Virginia native, had swept into Ann Arbor a year earlier by declaring the Wolverines would not lose a game in 1901, and they did not for the next four years.

Led by two-time All-American tailback Willie Heston, Michigan became the first national power from outside the Ivy League. UM went 56 games without a loss — the second-longest unbeaten streak in college football history.

For the 1902 Wolverines, Notre Dame was supposed to be the latest bug-on-the-carriage nuisance.

Its program was nearly a decade younger, established in 1887 when two former Notre Dame students on the Michigan football team reportedly contacted their former school’s intramural director to set up an exhibition game in South Bend.

“It was not considered a match contest, as the home team had been organized only a few weeks,” the Scholastic wrote. “And the Michigan boys, the champions of the West, came more to instruct them in the points of the Rugby game than to win fresh laurels.”

Fifteen years later, the program retained the same improvisational quality. Notre Dame’s independence was not yet a sign of its might but a bitter symbol of rejection — and, many surmise, anti-Catholic discrimination.

Although the Irish had won eight games the previous year and featured the 6-foot-3, 230-pound Salmon, the school’s first All-American, the team lacked direction. Notre Dame could not gain membership alongside Michigan and Chicago in the Western Conference; James Faragher was its sixth coach in nine years, and attrition and injury had pared the roster.

The week of the Michigan game, a story in the Scholastic implored students to give their bodies to the cause.

“The Varsity needs plenty of practice during the coming week for the Michigan game, and it is up to you, fellows, to see that they get it,” the newspaper wrote, according to Mr. Kryk’s book.

Among those who helped: James McWeeney, the 36-year-old police chief of South Bend.

The Irish’s trip to Toledo figured to be ugly.

“Many of the uninitiated [fans] were not sure what to expect,” one spectator, Aaron Cohn, told The Blade for a 1952 story on the game. “All they could reason out was that Michigan ... was expected to win by nothing less than several hundred points.”

Wolverine wake-up

Instead, something else altogether happened.

For a half, The Blade reported, Notre Dame “outplayed the Wolverines.”

With the rains of a night before rendering the field a soupy, sawdust-peppered mess, the game devolved exclusively into a brutal head-on test of wills — and the Irish were braced for a fight.

Notre Dame was spurred on by halfback Louis Salmon, who made repeated long gains against the Wolverines. Michigan won 23-0.

Salmon was “knocked out no fewer than four times,” Mr. Kryk noted, but woozily returned time and again. The red-headed back’s bruising runs kept the ball in Michigan territory most of the first half, with one drive ending as deep as the Wolverines’ 5-yard line. The Irish trailed only 5-0 at halftime.

The running of Heston, a 5-foot-8 burner whom Yost decades later called the greatest player he had ever seen, and others eventually wore down Notre Dame in a 23-0 Wolverines victory. Yet the next day’s headlines centered on the upstart Catholics. They had given the era’s most powerful program as much of a challenge as anyone.

The Detroit Free Press called it the Wolverines’ “toughest proposition” in two years.

“A great game,” The Blade extolled, “and one that will be remembered for years to come.”

“The game put Notre Dame on the football map in the Midwest in that, wow, they held that Michigan team to a 23-0 loss, which is as close as even Chicago could get to Michigan,” Mr. Kryk said in a phone interview. “That was the first time Notre Dame raised any eyebrows outside South Bend, Indiana.”

On the other sideline, the day kindled tensions that would soon reach an impasse.

Yost accused the Irish of dirty play — Notre Dame’s nose tackle was twice penalized for slapping the ball as it was snapped — and slugging Wolverines players, although Mr. Kryk notes that only Michigan’s Curtis Redden was ejected. The left end was seen punching Frank “Happy” Lonergan.

Baird also was not pleased, though for different reasons.

“The attendance was not as large as I had anticipated,” he told The Blade. “It was thought the people of Toledo were anxious to see college football, and for that reason the game was played here. I am not able to state now whether we will bring a game here next season.”

He would not. Yet the legacy of Toledo’s brush with big-time college football carried on.

Mr. Kryk points to the game as the first of three formative contests in early Notre Dame history.

The second was in 1909 when Notre Dame beat Michigan 11-3. It was the Irish’s first win over UM and led to Yost’s enduring refusal to play Notre Dame. The teams would not play again until 1942 — or two years after Yost retired as athletic director.

Then came Notre Dame’s trip to West Point, N.Y., in 1913. Emboldened by these earlier successes to expand the program’s reach, first-year coach Jesse Harper scheduled road games against a line of powers: Penn State, Texas, and Army. Notre Dame won them all, including a 35-13 victory over the Black Knights that embedded the Irish once and for all in the country’s consciousness.

A nation of Catholics, subway alumni, and college football fans would come to learn by heart — whether they wanted to or not — the program’s guiding hymn.

The “Victory March” begins:

“Cheer, cheer for old Notre Dame,

Wake up the echoes cheering her name ... ”

The team with the gold helmets and the golden past now claims 865 victories, 11 national championships, seven Heisman Trophy winners, and its own national television contract. On Jan. 7, after two decades spent searching for past glory, the Irish will attempt to wake up the echoes once more.

Echoes that began in downtown Toledo.

Contact David Briggs at: dbriggs@theblade.com, 419-724-6084 or on Twitter @DBriggsBlade.