STONE LABORATORY TESTING

Algae-produced microcystin may follow blooms across lake

Weather to determine path; islands remain on lookout

8/21/2014

Wildlife biologist Tory Gabriel, Ohio Sea Grant fisheries outreach coordinator, holds a jar of microcystis algae pulled from Lake Erie.

THE BLADE/TOM HENRY

Buy This Image

Wildlife biologist Tory Gabriel, Ohio Sea Grant fisheries outreach coordinator, holds a jar of microcystis algae pulled from Lake Erie.

GIBRALTAR ISLAND, Ohio — From the boat docks of Ohio State University’s Stone Laboratory, practically a stone’s throw from the party headquarters known as Put-in-Bay tiny green specs are in the early stages of bunching up and floating on Lake Erie’s surface.

It’s been an all-too-familiar sight to Great Lakes scientists who use that lab, the oldest freshwater field station in the United States, since 1995.

For the moment, they have no reason to panic.

RELATED CONTENT: Filters might work on toxins, but experts say more tests needed

But they also know those tiny green specs are nature’s way of putting them on notice that the 2014 algae bloom is heading their way.

Four to six weeks from now, that part of Lake Erie could have thick, noxious mats that put the Lake Erie islands — including one of Ohio’s most popular tourist destinations — on high alert. At the very least, scientists said, it likely will have lake water with a slightly greener tint, a St. Patrick’s Day-like hue similar to what it is now.

It all depends on wind, heat, rain, and other weather conditions.

While Great Lakes scientists are getting better at predicting the path of algae blooms, they said they are limited by how far in advance meteorologists can predict the weather.

Jeff Reutter, Ohio Sea Grant and OSU Stone Lab director, said satellite images the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration are getting from the European Space Agency are among the most powerful forecasting tools.

Rick Stumpf, a NOAA oceanographer in Maryland in charge of that program, said images are expected to become higher resolution and more frequent in two years, once a new satellite is deployed.

Blooms typically start in the Toledo area, where the Maumee River, which is highly enriched by phosphorus and other nutrients applied to farmland, flows into warm and shallow western Lake Erie’s Maumee Bay.

From there, the bloom grows like a big, green blob north to Monroe, across southwest Ontario, along the Ohio Lake Erie shoreline, or in the open water.

But there is no direct, linear path or any guarantee it’ll stick together. Often, it breaks apart.

Rarely does it get past the Lake Erie islands.

The record 2011 bloom is the only one — in modern history, at least — during which free-floating microcystis penetrated Lake Erie’s much deeper and colder central basin.

It is the only bloom that made it to the Cleveland metro area, though by then it was far too diffused to pose the kind of threat it did to Toledo’s raw-water intake on two occasions this month.

Based on runoff data and this summer’s weather patterns, NOAA said the total biomass of this year’s bloom will likely be only about half what it was three years ago and shouldn’t come close to reaching the Cleveland area.

But scientists are learning more and passing along their research once they become comfortable with it, from the role of climate change to the degree by which phosphorus can even fall from the sky.

Laura Johnson, Heidelberg University research scientist, said the annual input of 504 metric tons of phosphorus from the Detroit waste-water treatment plant is only about a sixth of the 3,000 annual metric tons from the Maumee River watershed, which is 73 percent agricultural.

Less than 8 percent of the Maumee’s phosphorus comes from sewage overflows, she said.

Newer pieces of information discussed during an annual two-day workshop for science writers at Stone Laboratory this week included a discussion of often-overlooked microcystis that forms in the Maumee and other tributaries during the spring.

Justin Chaffin, Stone Lab research coordinator, said research on those blooms show they are distinct and unique, that what forms in the tributaries is not the foundation for what later forms in the lake.

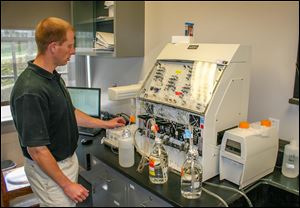

Inside the water quality laboratory of OSU’s Stone Laboratory, Justin Chaffin, the lab’s research coordinator, measures phosphorus and other nutrients found in the water.

The role of nitrogen also is becoming bigger. More nitrogen appears to create more toxin.

“Phosphorus is still the most important nutrient. It creates the bloom,” Mr. Reutter said. “Nitrogen may deal with the severity of the bloom and the toxicity of it.”

Yet western Lake Erie continues to teem with life.

Jeff Tyson, Lake Erie fisheries program manager for the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, said walleye and yellow perch reproduction remains strong.

Mr. Reutter said a sample of the lake’s muck drawn earlier this week was as good as any he’s seen for tiny organisms.

Tory Gabriel, Ohio Sea Grant fisheries outreach coordinator, found a couple of mayfly nymphs in the lake’s muck while taking a group of journalists out on a research vessel on Tuesday.

He said Lake Erie incurs a blow from every algae outbreak, but it is hardly close to being on a death knell.

Mayflies, he noted, are the sentinels of water quality.

“The blooms are a pretty concentrated phenomenon,” Mr. Gabriel said. “You can have a pretty healthy lake and still have algal blooms.”

The blooms shouldn’t be there. They’re a symptom of the lake being grossly overfed by nutrients, he said.

Microcystis is native to Lake Erie, but isn’t supposed to proliferate the way it does, Mr. Gabriel said.

“It’s not an invasive. It’s supposed to be here,” he said. “We’re feeding it way too much.”

There are more than 100 forms of algae in Lake Erie, most of them good for the food chain, Mr. Chaffin said.

“Lake Erie produces the most fish of all of the Great Lakes because it has the most algae,” Mr. Chaffin said, a reference to how healthy algae forms a basis of the food chain.

There are more than 80 varieties of microcystis, the main algae that produces toxic microcystin, Mr. Chaffin said.

But it turns out microcystis isn’t the only cyanobacteria classified as a harmful algae bloom that produces the toxin known as microcystin.

So does one called planktothrix, the subject of a major research project funded by Ohio Sea Grant.

“This is an overlooked species that’s often in Sandusky Bay,” Chris Winslow, Stone Lab associate director, said.

Microcystis, commonly referred to as “Mike,” is one of the lake’s notorious Big Three of Great Lakes toxic cyanobacteria — organisms that are actually bacteria but act like algae.

Cyanobacteria get their name from their blue-green hue.

Mike attacks the liver. The other two — “Annie,” short for anabaena, and “Fannie,” short for aphanizomenon, attack the central nervous system.

All three are believed to be 3 billion years old.

Mr. Chaffin said the buoyant version of anabaena that bubbles to the surface was given the scientific name of dolichospermum by taxonomists in 2009 to distinguish it from the heavier version of anabaena that spends most of its life on bottom of the lakes.

That anabaena cousin is called Dolly, for short.

Scientists continue to use as many research tools as they can to track and better identify algae as it forms.

The lab’s remote-operated vehicle is almost a 10-year-old relic in comparison to other technology. Once one of the newest and most important gizmos, it is an underwater camera that can move around the lake on command, like a robot sending images above the surface in real-time.

“It gives operators a view of the underwater world,” Matt Thomas, Stone Lab manager, said.

Awaiting approval for deployment this fall is a high-tech buoy with its own weather station and instrumentation capable of reporting wind direction, wind speed, temperature, and levels of phosphorus, dissolved oxygen, PH, and chlorophyll via a solar-powered radio uplink.

Donated by its manufacturer, Fondreist Environmental Inc., the buoy will be anchored on the north side of Gibraltar Island once the Coast Guard gives its approval, Chris Winslow, Stone Lab associate director, said.

Stone Lab has joined Toledo and Oregon in recent years with lab equipment to do its own microcystin tests.

Its clients include Put-in-Bay, Middle Bass Island, Kelleys Island, Marblehead, Camp Patmos (a Christian youth camp on Kelleys Island), Vermilion, and Norwalk. It also tests samples of the open water brought in by six Lake Erie charter boat captains. Sampling frequency varies, but many are weekly during the algae season, Mr. Chaffin said.

A test performed Tuesday showed no detectable levels of microcystin for all clients except the charter boat fish captains, who brought in some samples of open water with elevated levels, he said.

“It’s going to cost a lot of money to fix the problem. But it’s going to cost a lot more if we don’t,” Mr. Chaffin said.

Contact Tom Henry at: thenry@theblade.com, 419-724-6079, or via Twitter @ecowriterohio.