Poor decisions accelerated decline of Toledo's once-bustling downtown

Proposed Jackson boulevard changes could be next mistake

4/26/2015

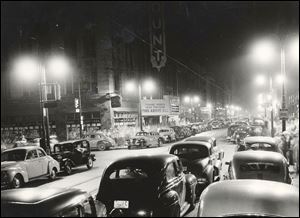

It’s hard to believe now how vital, congested, and busy downtown Toledo was in earlier days. Old photos, such as this one taken in August, 1942, cars filling the Adams Street near the Huron Street intersection.

THE BLADE

Buy This Image

The sad shape of large sections of downtown Toledo — rows of vacant buildings, gap-tooth sections with empty structures separated with parking lots, looming giants of brick and steel that haven’t seen habitation in decades — didn’t just happen.

While the decline of manufacturing, the spread of city water lines outside the city limits, and unfettered suburban growth each contributed to pulling companies and people out of downtown for decades, bad decisions by public officials and the titans of Toledo industry accelerated the demise, many now admit.

Toledo attorney R. Michael Frank, a former Toledo-Lucas County Port Authority board member, said the city’s elected and industrial leaders failed numerous times to think beyond immediate needs when tearing down buildings and erecting new structures. The bad decision-making stretches back to the period of “urban renewal” in the 1960s and 1970s that he and others disdainfully dubbed “urban removal.”

SEE ALSO: Boulevard’s roots can be traced back to Paris

Some of Toledo’s historic downtown buildings have endured for a century — albeit vacant — while others seem to have been built with a 40-year expiration date sticker hidden within the masonry.

“They spent millions to build a [county] jail that only lasted 40 years; they spent millions to build the [Community Services] building and it only lasted 40 years,” Mr. Frank said. “In Europe, buildings last for centuries. The jail they spent millions on is obsolete after 40 years. Now they want to tear out the boulevard they built 40 years ago.”

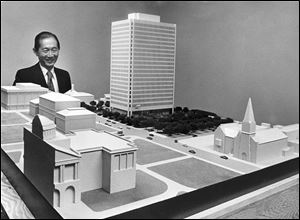

Renowned architech Minoru Yamasaki designed the Jackson Street boulevard. His intent was to connect One Government Center, which he also designed, to the Maumee River.

It came to light last week that the Toledo Area Regional Transit Authority wants to destroy part of the Jackson Street boulevard in the heart of downtown — a four-block esplanade full of three-decade old gnarled crabapples — created by world-renowned architect Minoru Yamasaki during the same time he designed One Government Center.

Mr. Frank said razing buildings and changing landscapes provides a benefit to the construction trades. “They constantly want to tear down and rebuild in order to carry construction jobs.”

A matter of heat

None of this means that there aren’t parts of downtown being revived. Look at the areas surrounding Fifth Third Field and Huntington Center and new businesses popping up along Adams Street in the Uptown area.

The late Mayor D. Michael Collins often proclaimed that downtown was on the precipice of a huge upswing with ProMedica’s $50 million plans to relocate the health-care system's headquarters to the century-old Toledo Edison steam plant, which has sat vacant for decades along the Maumee River downtown.

The historic steam plant on Water Street, which originally supplied heat to downtown businesses, shut down in 1985. Rising heating costs or installing a new heating system contributed to the closing of downtown's Petrie’s store at 501 Adams St. — now the site of a parking lot. The store operated on the corner for five decades.

Many other marginal downtown businesses also closed their doors after the plant was shut down because the cost of new heating systems was too high, leaving empty buildings littering downtown.

Peter Ujvagi, Lucas County’s chief of public policy and legislative affairs, who was a Toledo councilman in the early 1980s, said allowing the plant to shut down without “appropriate arrangements” for downtown businesses that used its steam heat was the biggest mistake of his political career.

“Financially, it made sense to close down the steam plant because that type of power and heating was no longer economical at that point. That was a good policy decision,” Mr. Ujvagi said. “The unintended public policy consequence was a lot of buildings became obsolete, and I am convinced a lot of those became parking lots that contributed to the gap tooth nature of our downtown.”

Another era

It’s hard to believe now how vital, congested, and busy downtown Toledo was just a few decades ago. Old black and white photos show crowds of people cramming the sidewalks, hundreds of cars filling the streets, dozens of businesses lining downtown blocks.

There were four major department stores downtown — LaSalle’s, Lamson’s, the Lion Store, and of course the legendary Tiedtke’s. There were even more locally owned banks and business headquarters.

It’s hard to believe now how vital, congested, and busy downtown Toledo was in earlier days. Old photos, such as this one taken in August, 1942, cars filling the Adams Street near the Huron Street intersection.

Toledo Trust, First National Bank of Toledo, Ohio Citizens Trust Co., and Mid American National Bank & Trust Co. were downtown, and there were also four local thrifts: First Federal Savings and Loan Association, People’s Savings, United Savings & Loan Association, and Toledo Home Federal Savings & Loan Association. All were later acquired and are now part of larger banks in Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati.

Up until the 1970s, there were seven Fortune 500 companies that had their headquarters in Toledo, and five were within a few blocks of each other downtown: Owens-Illinois Inc., Owens Corning, Libbey-Owens-Ford Co., Sheller-Globe Corp., and Questor Corp. Owens Corning is the only one still downtown and still in the city.

Even as late as the mid-1970s, there were four new-car dealerships in or near downtown.

By some estimates, the number of downtown workers peaked at 40,000-plus in the early 1950s, but 31,000 downtown jobs remained in the late 1970s, dropping to 25,000 by the late 1980s, and to fewer than 20,000 in the private sector today.

Urban renewal

A decade before, in the 1960s, Toledo City Council approved urban renewal plans that included the Old West End, the area near the old Edison steam plant, and a seedy area along Cherry Street near downtown.

The plan called for the development to be known as Vistula Meadows. As recommended to council, the plan called for the acquisition of 101 acres over 37 blocks at a cost of $17.4 million supplied by the federal government. It was initiated in 1959 by Downtown Toledo Associates, and Vistula Meadows was to be an extreme makeover for the Cherry Street corridor, from the Maumee River to Spielbusch Avenue.

What once was a bustling commercial hub had turned into a string of bars, sleazy hotels, restaurants, apartments, pawn shops, storefront churches, and vacant buildings collectively referred as Toledo’s “Skid Row.”

In an effort to improve the entryways to the heart of the city, 88 acres of blight from Cherry Street along Summit to Jefferson and down to the Maumee River were flattened and cleared.

By 1970, more than 200 brick commercial structures were gone from downtown and the near downtown area.

Construction for the median for Jackson Street boulevard is shown in this 1981 photograph. The crabapple trees planted in the median have grown there for 30 years.

But what hurt downtown more was the decision to allow the unfettered proliferation of suburban sprawl. Developers were given free rein to build, and build they did — including the Westgate shopping center and the Franklin Park, Southwyck, Woodville, and Northtowne shopping malls. As the malls opened, the downtown department stores closed.

By the mid-1970s, Tiedtke’s and Lamson’s were gone; the Lion Store closed in 1980, and Lasalle’s shut its doors in 1984.

Along with them went Woolworth’s, B.R. Baker, Damschroder’s, H.O. Nichols, Bond’s, and Jack’s Mens Shop, and the women’s stores of Petrie’s and Stein’s.

Downtown suffered from other factors, such as the outflow of businesses to suburban locations such as Maumee’s Arrowhead Park beginning in the late 1970s, and corporate downsizings beginning in the 1980s.

Black community

Toledo’s African-American community also was hit hard by the urban renewal program, said former Toledo Councilman Wilma Brown.

Until the early 1970s, Dorr Street was lined with homes, offices, stores, and bars — many of them owned by prominent black businessmen creating a growing black middle class in the city. But by the 1970s, white politicians, concerned about the decay of the buildings and an increase in crime, marked the area for urban renewal. By 1979, buildings on both sides of the street had been bulldozed and Dorr was widened to four lanes.

Many of the black businesses were to never open again.

“All they did was make it wider so white people could get through to the suburbs,” Ms. Brown said. “Urban renewal did nothing but destroy our whole community and there was never any effort to bring businesses back.”

Mr. Frank said many of the so-called urban renewal decisions were unwise.

“It had to do with tearing down homes in the inner city and not replacing them with residential properties,” he said. “It also had to do with using urban renewal funds to rebuild downtown where no one lived at the time.”

Former Ohio Supreme Court Justice Andrew Douglas, who was a Toledo councilman from 1961 through 1980, was chairman of the urban renewal committee and defends many of its decisions.

He said many decisions were made to improve downtown during the last five decades

“The area between Cherry Street and Jefferson all the way down to Monroe looked like the Gaza Strip — it was all bombed out. It was all fired out,” Mr. Douglas said. “Compared to how it looked then, today is a major improvement.”

Mr. Douglas recalls a lot of behind-the-scenes dealing with high-ranking city and state officials that also included business leaders such as the late Paul Block, Jr., co-publisher of The Blade during that period.

Mr. Douglas recalled a last-minute trip to Columbus with Mr. Block to meet with Ohio Gov. James Rhodes to make a pitch for a new government building to be built in Toledo.

“We didn’t have any money and they asked, ‘How are you going to make your payments?’ and I pledged our share of the local government fund, and they all agreed to do that,” Mr. Douglas said. “We never missed a payment.”

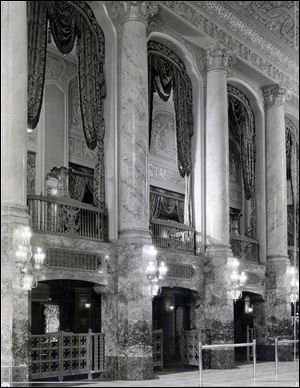

While Mr. Block’s role in pushing forward the construction of One Government Center, the Jackson Street boulevard, and the creation of the former Medical College of Ohio were lauded by Mr. Douglas, his role in events that led to the razing of the former Paramount Theater downtown are remembered as a mistake.

The Paramount Theater was built in 1929. It was considered by many to be the jewel of downtown Toledo’s theaters, yet it was demolished in 1965 to create more parking spaces.

Mr. Block allowed the old Paramount Theater — considered the grandest of the old downtown theaters — to be razed in 1965 to make way for additional parking for the newspaper.

Mr. Ujvagi speaks with disdain in his voice as he talks about watching the Paramount be destroyed.

“It was one of the most beautiful buildings … and the wrecking ball was knocking it to pieces,” he said. “The Valentine is very important but it doesn't hold a candle to what the Paramount was,” Mr. Ujvagi said.

Three decades after the Paramount’s destruction, The Blade pushed for and helped finance the renovation and modernization of the Valentine Theatre, which still retains its turn-of-the century charm and décor. It was last of the downtown theaters and the only one to survive.

A defining point

Architect Byron West, who designed many downtown buildings, including the KeyBank building that is slated to be part of ProMedica’s new downtown headquarters, and the Shumaker Loop & Kendrick law offices on Jackson, said the Jackson Street boulevard is not just another street in Toledo but a defining point that provides a boundary for the downtown business district.

“Cities which retain their vitalities are the ones that in some way or another have constraints in their geography such as [a] river, mountain, or a lake,” Mr. West said. “You have got a boulevard with trees, shrubs, and flowers. It makes more of a statement that if it just was a street with traffic running in both directions.”

Mr. West knows too well about the demolition of downtown landmarks.

The Community Services Building, which he designed as a tribute to the Stranahan family, became the victim of the wrecking ball in 2010 after the United Way of Greater Toledo built a smaller building on the same property to the northwest.

“In my judgment, it was a real tragedy. It was a building that was one of [a] kind,” he said.

The six-story building served as a bookend on Jackson for St. Clair Street with the SeaGate Convention Center being the other bookend at Jefferson Avenue, said Mr. West, 82.

“It made a strong definition in the downtown, and that has been lost. I thought they lost a helluva a good building,” he said.

Pat Green, a former Blade reporter who covered city government in the 1960s and downtown redevelopment until the 1990s, said the vision of the late Minoru Yamasaki, the architect who designed the original World Trade Center in New York, to have the Jackson Street boulevard as a focal point to connect Government Center to the Maumee River was an effort to redevelop that area of downtown.

“I don’t think it was an ill-conceived plan. It was something that opened up that section of the downtown, which was not exactly attractive at the time. Looking back on it, I think it was a pretty good idea,” she said.

At that time, the riverfront on Summit was being revitalized with the construction of One Seagate, the old Portside Festival Marketplace, and the building that would become the headquarters of HCR ManorCare.

“The plan to develop Jackson into a boulevard was the city’s component of the whole plan to link Government Center to Portside and One Seagate,” Mrs. Green said.

Contact Ignazio Messina at: imessina@theblade.com or 419-724-6171 or on Twitter @IgnazioMessina.