THE GREAT MIGRATION

Ohio was land of hope for many black families

African-Americans flocked to Toledo in early 1900s

2/14/2016

Morrell Fonfield, left, holds a photo of their grandmother Florence Allen, while her sister, Ruby Hill, holds a photo of their father, Wilson Allen, in Mrs. Hill’s Toledo home.

THE BLADE/LORI KING

Buy This Image

Morrell Fonfield, left, holds a photo of their grandmother Florence Allen, while her sister, Ruby Hill, holds a photo of their father, Wilson Allen, in Mrs. Hill’s Toledo home.

Ruby Hill and Morrell Fonfield were very young and still new to Toledo when their father, Wilson Allen, took them and their brothers to visit the old Toledo Trust bank where he worked as a janitor.

It was an experience the family might never have known had they remained sharecroppers in Oxford, Miss.

Their mother, Ematha (Grussie) Ramey Allen, dressed up her children for the trip where they saw the bank vault, saw how money was handled, and where they were introduced to the guards, tellers, and the president. As if it was only recently, Mrs. Hill recalls what the vice president, whom she recalls was Roy Kraft, said to her father that turned out to be prophetic.

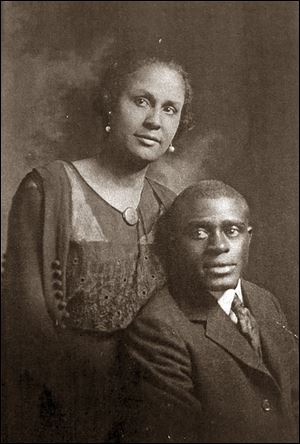

Louise and Louis Allen. Louis is the uncle of Morrell Fonfield and her sister Ruby Hill. Louis is the second member of the Allen family to move from Mississippi to Toledo, and invited family members migrating here to live with them until they found their own place.

“[He] said, ‘Wilson, I saw you had your children. I tell you Wilson, tell your children to get an education because the day’s coming when there will be a black president and black tellers,’ ” Mrs. Hill said, adding that was difficult to grasp in an era when black Americans had limited access to opportunities. “Can you imagine seeing something like that back in that day?”

After the bank visit, the Allen children had an experience that black and white Toledo children of all ages once shared.

“Then [our father] would take us to Tiedtke’s and we’d get malts or hamburgers,” said Mrs. Hill, 83, who lives with her sister, Mrs. Fonfield, 84. “And yes, I remember the cheese; cheese and hard rolls were the first thing you saw.”

The early 20th century racial environment for black families wasn’t completely welcoming north of the Mason-Dixon line, but it was better than life in the South, which was why the Allens and thousands of other African-Americans made the trek North.

Earlene Gilbert did not come to Ohio during the Great Migration, and has only lived in Toledo for a few years. However, she remembers the impact the migration had on her Montezuma, Ga., school, where her eighth grade class started with 40 youngsters.

“Four years later we had 11 seniors. When the boys got big enough, they would migrate,” said Mrs. Gilbert, who graduated from what was then Tuskegee Institute and went into the Air Force as a second lieutenant. “When we got to graduation, there were four boys and seven girls left in the class.”

Mrs. Gilbert, 79, described the migration as a system in which some who had already migrated North would take others back with them after visiting the South.

“They would come back and show off their new cars and new shoes and stimulate some more to go back,” said Mrs. Gilbert, who has lived all over the country because her late husband, Charles W. Gilbert, traveled for his job as an assistant regional commissioner for the Internal Revenue Service. He never migrated North.

State of opportunity

Pulitzer Prize winner Isabel Wilkerson, a guest speaker at last spring’s “Authors! Authors!,” talked about the Great Migration of some 6 million black Americans from the South between 1915 and 1970. Her book, The Warmth of Other Suns, tells the stories of African-Americans who left southern farms, plantations, and fields for a more favorable life in the North and West.

Clyde Hogan holds a picture of his father, William Hogan and his mother, Mildred Hogan. The Hogans moved to Toledo from Florida when Clyde was about 5 years old. The number of African-Americans in Toledo reached 40,000 by 1960.

“Ohio was one of the great receiving stations of the Great Migration, one of the states that people dreamt of. Whenever I’ve been to Ohio, conversations go to the state of Alabama, which sent so many people to Ohio,” Ms. Wilkerson said during a Blade interview.

Three years after the city of Toledo was incorporated in 1837, 54 African-Americans were among the 1,188 residents, according to the sixth U.S. Census. By the end of the 19th century, about 1,060 of the city’s 81,434 residents were black. In 1920, the black population had risen to 5,691, and by 1960, it was 40,015.

Census figures put Toledo’s population at 281,031 in 2014, with 27.2 percent African-American.

While Mrs. Hill and Mrs. Fonfield’s three younger brothers have since passed, the sisters are well known in Toledo’s Christian community. Mrs. Fonfield is a lay minister at Braden United Methodist Church, which their family was instrumental in founding.

“My uncle, who came first, used to travel all over,” said Mrs. Hill.

As the men pondered their next stop, it was a toss-up between Kansas City and Toledo. The friend chose Kansas City. In 1917, that uncle was the first in the family to come to Toledo, where he found menial work at Boody House downtown on Summit Street and at the Toledo Club on 17th Street.

More male relatives followed, leaving behind lives as sharecroppers for jobs at some notable Toledo firms, some of which no longer exist: Toledo Trust, Art Iron, Willys Overland, and Autolite among them. When the men sent for their families, they came on a train. The women found jobs as day workers, maintaining the homes of whites.

“They wanted a better life for the children, better jobs, better opportunities, and better education,” Mrs. Hill said. “My father was a man of vision, and the family men were hardworking men who wanted better lives. If we’d stayed, probably we would have continued to pick cotton. My father always felt that there [would be] a better day.”

Mrs. Hill worked as an LPN, nurse’s aide, and at a factory. Mrs. Fonfield — who lived in Boston some 30 years then returned to Toledo — was a social worker. In fact, anyone who knows this tall, proud woman might see her walking through the downtown area, as she still works as a receptionist at One Government Center.

The right decision

Clyde Hogan’s family moved to Toledo from Florida when he was about 5 years old. His father, William Hogan, a graduate of Edward Waters College, had built the family a home in Ocala, Fla. Though his father taught in rural schools, his earnings were not enough to sustain a family, as Mr. Hogan said he “was barely making ends meet.”

He said an aunt, who was first in the family to move North, beckoned other relatives to follow, and they did. However, when the elder Mr. Hogan was laid off from work at a factory, he sent the family back to Ocala, Fla., but it wouldn’t be a permanent move.

“We were there for about a year and then we moved back to Toledo in about 1943 when he was called back to his job working for National Supply,” said Mr. Hogan, 78. He said his mother, Mildred Hogan, worked at the old Posner’s Delicatessen downtown.

As a young man, Mr. Hogan found life in the North “considerably better, but not that great.” One improvement, he said, was not having to sit in the balcony in a movie theater.

“We could walk through the front door and get a seat in the movie theater. That was different. That stunned me and my brother,” Mr. Hogan said. “I remember going to the movies and various places in the South; when you bought a ticket you walked up the fire escape to the balcony.”

The University of Toledo graduate rose through the ranks at the Dana Corp., where he began as a machine operator. He retired after 41 years as director of equal opportunity affairs.

Mr. Hogan’s wife Birdie, 76, a retired deputy clerk for the Lucas County Family Court, migrated in 1950 with her family from Kentucky. Mr. Hogan said an older brother worked some 30 years at what’s now GM Powertrain.

Mr. Hogan tells the story of what could have been a life-altering experience when the family stopped in a small rural Georgia town to gas up as they made the trip North from Florida.

“Mom said, ‘Be on your best behavior.’ A white man said [to my father] ‘What will you take for that car, boy?’ ” said Mr. Hogan, adding that his father was upset. “He couldn’t afford any confrontation. There was one white man in the crowd who had a cooler head and he persuaded the one man to cool down and leave him alone.

Clyde Hogan holds a picture of the home he was born and lived in until the family moved to Toledo. Many black families found better jobs and a better racial environment in the North.

“That man was going to force my dad to [give him] the car. Dad said, ‘This is my only means of getting my family North,’ but the man didn’t care. My dad was an outspoken person, [but] I know he had to cower somewhat for fear of what might happen to him. I know that scenario had played out with numerous other families who also were on that trek to the North.”

Though that experience upset his father, Mr. Hogan said his father and brother continued to travel back to the South. Clyde Hogan, however, was not allowed to go back South with them because his father feared that his son’s outspokenness would put his life at risk.

“I never went South again until I got drafted in the Army; I was posted in Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri,” said Mr. Hogan, a member of Warren AME Church where he sits on the Vision Empowerment and men’s usher boards.

Looking back, does he believe it was worth moving from the South to the North?

“Yes, I do,” said Mr. Hogan. “I know things have gotten a lot better down there, but it was the right move for us at that time. I know my life is a lot better than it might have been had I stayed and been raised there. That’s not to say life is not without challenges here, but in comparison, I think this was the better choice.

“One of the things that influenced my life and the outcome of my working career was going through the trials and tribulations of coming to Toledo. In finding a job and going to school, there was always something you had to deal with,” he said, referring to his white “counterparts.”

“You always had to be above average to succeed and you had to work harder to succeed. My Dad made me want to work harder to show people that I could do more, and consequently, that’s how I ended up as director of equal opportunity affairs.”

Contact Rose Russell at: rrussell@theblade.com or 419-724-6178.