SOUTHERN REVIVAL

UT grad’s southern roots deep

Engineer built firm in Atlanta

2/9/2017

Birdel Jackson is surrounded by family photos and documents in his Alpharetta, Ga., home. He came to Toledo for college in the 1960s.

THE BLADE/JETTA FRASER

Buy This Image

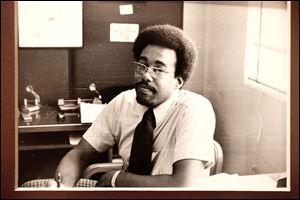

Birdel Jackson sits in his office with the Environmental Protection Agency in Atlanta in 1972. Mr. Jackson in his travels would report illegal discrimination to the agency.

ALPHARETTA, Ga. — Cotton sent Birdel Jackson to Toledo.

Specifically: The acres of Arkansas cotton grown on land purchased after the Civil War by his freed great-great grandfather and passed on to descendants.

When Mr. Jackson studied civil engineering at the University of Toledo, it was cotton — and his grandparent’s generosity — that covered the cost.

He arrived on campus in 1963 with a steamer trunk full of suits and ties, clothes he’d later swap for Chuck Taylors, Levi’s, and a UT sweatshirt. He was the only black student in his four-man dorm room.

Long before he came to Toledo, generations of Jacksons had worked to give him opportunities.

Their efforts “made it much easier for us to survive in spite of all this segregation and restrictions of where you could go and what you could do,” said Mr. Jackson, 71, who owned a major engineering firm and has lived in the Atlanta area the last 40 years.

He was born in 1945 in Memphis and spent his boyhood in a brick house built by his great-grandfather. The carefully chosen neighborhood was a block from school and across the Mississippi River from Ebony, Ark., the black farming community where the family grew cotton and ran a general store stocked with everything from caskets to cookies.

VIDEO: Birdel Jackson discusses growing up in the South

His parents moved their two children to the East Coast in 1959.

Birdel Jackson holds photographs of his mother, Leslie Ann, and father, Birdel Jackson, Jr., in his Alpharetta, Ga., home. His parents would take him on summer vacations to escape the racial tensions in the South before the family relocated north.

His father transferred jobs with the post office, and they joined a flow of African-Americans headed north.

The South crackled with racial tension. In 1954, the burned body of a local African-American farmer was found chained to a tree mere miles from the Jackson farm, and the family once gave up some property to spare the life of a relative.

Even before relocating north, Mr. Jackson’s parents took him on summer vacations to escape.

“We were getting out of the South. My mother always said, ‘We want you guys to experience not ... being oppressed all year,’ ” he said.

Virginia-born and New Jersey-raised, his mom, Leslie Ann, scanned the skies for enemy airplanes as an observer during World War II, rode horses, and wrote poems. His father, the second of three Birdels, studied agriculture and trained as a sailor to integrate the U.S. Coast Guard.

ABOUT THE SERIES

African-Americans are returning to the South in record numbers, reshaping a region millions of blacks abandoned during the Great Migration. Reporter Vanessa McCray and photographer Jetta Fraser spent a week driving through Georgia and Mississippi and visiting former Toledoans.

During Black History Month, The Blade tells their stories.

Sunday: Gail Rayford-Ambeau

Monday: Rev. Floyd Rose

Tuesday: Anne Brodie

Wednesday: George Armstrong

Coming Sunday: Young, educated blacks are leading the exit south. What can Toledo do to retain these bright minds?

His mother didn’t tolerate the racism she encountered in Memphis. She drank from white-only water fountains and objected when store clerks helped a white customer first.

“Mom would say, ‘Oh no, my money’s green. You’re taking my money right now,’ ” he recalled.

Mr. Jackson’s elementary school received old books from white schools. Sometimes, the black students would find the N-word scribbled on a page.

“It was a two-tiered system. We paid taxes, but we got crap. We got their used stuff, their castaways, their throwaways,” he said.

His parents jumped at the chance to move north as the Civil Rights fight gathered momentum.

Mr. Jackson pegs his coming of age to the movement’s milestones, summoning details and dates with an engineer’s precision.

During his senior year at a New York high school, protesters got hosed down for opposing segregation laws in Birmingham, Ala.

The week before his high school graduation, a white supremacist killed Medgar Evers in Mississippi.

In August, 1963, he was back in his childhood house in Memphis when he heard Martin Luther King, Jr., deliver his seminal speech in Washington.

The Toledo-bound freshman stood on the precipice of his next chapter and a nation’s uncertain future.

Birdel Jackson in his Omega Psi Phi fraternity cardigan on the quad at the University of Toledo in 1965.

Two weeks into his first semester, a bomb killed four girls in a black Alabama church. Days before Thanksgiving break, President Kennedy was assassinated.

“Everybody thought it was going to be a war, so a lot of folks from New York went back home,” Mr. Jackson said.

He stayed in Toledo and went to class.

He applied to UT after a recruiter stopped at his high school and was admitted based on the strength of his junior-year SAT scores. Mr. Jackson quickly got to know Toledo by hitchhiking.

Some motorists who picked up the black student assumed he was an athlete. When asked what sport he played he had a ready retort: “Mental gymnastics.”

There were a couple memorable cultural clashes. A white roommate once recorded over his favorite rock ’n’ roll songs, which is how Mr. Jackson got to know all the folk lyrics to Peter, Paul, and Mary’s “Puff the Magic Dragon.”

He joined the Omega Psi Phi fraternity and worked with a city engineering survey group.

After graduating in 1968, he worked in Pittsburgh and Washington before moving to Atlanta in 1971.

“When I came to UT in ’63 it didn’t occur to me to come back South,” he said.

But by the early 1970s, Atlanta was heating up. Ebony magazine named it one of the 10 best cities for black people.

Mr. Jackson snagged a job with the fledgling U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“I would go out to towns and inspect sewage treatment plants. Some places my boss would have to call ahead and say, ‘We sent a young black engineer out here. Get stuff squared away,’ ” he said.

In Chattahoochee, Fla., a restaurant locked the door rather than serve him and the eatery across the street had three restrooms — for men, women, and “colored.”

Birdel Jackson stands with his sister, Carol Ann, and his grandmother Gladys Davis Jackson in the late 1940s in front of the house built by his great-grandfather in Memphis.

In Wilmington, N.C., a motel proprietor claimed no vacancies, even though the black woman who cleaned the rooms told him there were no guests.

Mr. Jackson reported illegal discrimination to the federal agency, and held local politicians accountable.

“I wasn’t going to let it stand,” he said.

After a short stint in Indiana, he returned to Georgia in 1977. He did engineering work for Olympic venues when Atlanta hosted the games, and built his own firm.

He’s met many former northerners drawn to the South by its slower pace, warm weather, family ties, jobs, and affordable housing.

Toledo, however, has a place in his heart. College pictures hang in his memento-filled man cave, and he displays his diploma in an upstairs office.

He’s served on alumni association and foundation boards and returns often to ride in homecoming parades and attend other events.

Mr. Jackson established a UT scholarship named after his grandparents who helped him go to college.

It’s for civil engineering students and priority goes to African-Americans.

“He wants other students to have the opportunities that he’s been blessed with in his career. To me, there is no greater legacy. That is Birdel Jackson in a nutshell,” said Dan Saevig, UT’s associate vice president for alumni relations.

Contact Vanessa McCray at: vmccray@theblade.com or 419-724-6065, or on Twitter @vanmccray.