Prehistoric people hunted caribou on ancient Lake Huron ridge

10/29/2017

The prehistoric hunters that pursued herds of caribou on an ancient land bridge that crossed Lake Huron likely lived in what is today the Lower Peninsula of Michigan.

Tane Casserley

ALPENA, Mich. — At a time in our region’s history when the climate was much colder and the water level of the Great Lakes much lower, hunters pursued caribou across an exposed strip of land that connected what is now northeast Michigan to southern Ontario.

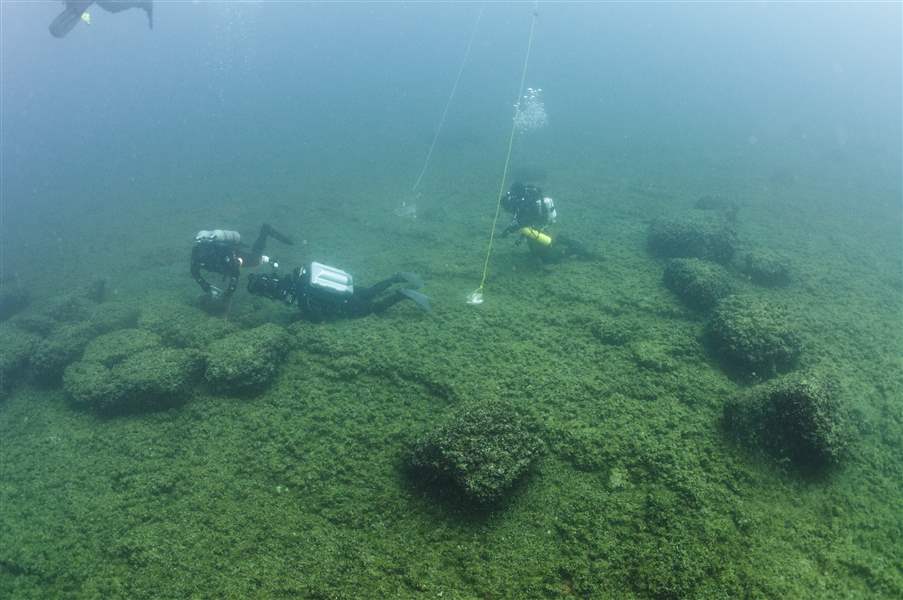

On the Alpena-Amberley Ridge, a 72-square-mile land mass that essentially separated Lake Huron into two large, post-Ice Age basins, archaeologists have discovered unambiguous evidence that hunters from about 9,000 years ago took part in organized hunts using drive lanes and ambush points. The hunting site on the bottom of Lake Huron identified in this research is regarded as the most complex hunting structure found to date beneath the Great Lakes.

The prehistoric hunters that pursued herds of caribou on an ancient land bridge that crossed Lake Huron likely lived in what is today the Lower Peninsula of Michigan.

University of Michigan professor of anthropological archaeology John O’Shea said his team has conducted simulation studies based on the layout of the site, located in about 120 feet of water about 35 miles southeast of here. The layout and the artifacts found there have led researchers to determine that these prehistoric caribou hunters from the Late Paleoindian/Early Archaic period varied their tactics based on the time of year and the migratory habits of the caribou.

Caribou, a large, elk-like species of deer that is native to some of the coldest regions on the planet, are well-adapted for the harsh climate they would have found here following the retreat of the glaciers. They survive in the tree-less tundra of northern Europe, Siberia, and North America today by migrating as much as 1,500 miles each year to reach summer feeding grounds and wintering areas where they survive on lichens.

Caribou are an essential food source to many indigenous people of the northern reaches, primarily hunted in North America and herded in northern Europe and Asia, where they are known as reindeer. The evidence found on the floor of Lake Huron shows how prehistoric people of the Great Lakes region used the topography of the landscape and other mechanisms to harvest caribou as herds migrated through the area.

“Late Paleoindian/Early Archaic caribou hunters employed distinctly different seasonal approaches," Mr. O'Shea said, according to the research. "In autumn, small groups carried out the caribou hunts, and in spring, larger groups of hunters cooperated."

Mr. O’Shea said that the fall migration of the caribou likely provided the best hunting opportunity, but, some of the structures below Lake Huron’s surface reveal that they were designed for a spring migration as the animals moved across the ridge from what is now Ontario to cooler areas to the north.

“The V-shaped hunting blinds located upslope from one of our study areas are oriented to intercept animals moving to the southeast in the autumn," Mr. O'Shea said. "This design differs from other hunting structures associated with alternative seasons of migration. Our simulation data indicates that the area was a convergence point along different migration routes, where the landform tended to compress the animals in both the spring and autumn."

Mr. O’Shea said lines of stone were used to funnel the caribou close to a series of hunting blinds and into a cul-de-sac type structure.

“The ridge is very narrow here, creating a natural choke point for herds in migration,” he said. “At that time when this was very, very cold tundra with clumps of birch in various places, the drive lanes were likely constructed of wood, so all we see down there now are the stones that were part of the drive lanes.”

He said the strategically placed stones and pieces of wood likely were enough to keep the caribou within the drive lanes and push them close to the hunters at the ambush points.

“It is very important to understand that caribou are not like the bison we see out west that will move more erratically,” he said. “Caribou tend to follow linear patterns — they tend to drive themselves — so these stones likely worked very well to drive the caribou into the kill zones or ambush positions.”

The research on the lake floor has indicated that the larger and more complex drive lanes would have required a larger hunting group working in unison, while some of the smaller V-shaped hunting blinds could have been used by small hunting parties that were aided by natural land formations that helped funnel the caribou toward them.

The research on the Lake Huron floor has been ongoing since 2009, with Mr. O’Shea adding that each season’s work not only reveals new information, but also raises additional questions. He said this past summer’s efforts focused on using sophisticated underwater photography methods to create 3-D models of the hunting structures to use as a more effective manner of showing the general public what these look like. The team also did bulk sampling along the Huron floor before shutting down the work in the lake for the year.

“We were looking to recover any cultural items that might be in the area, and what we’ve found looks like processing materials, not spear heads,” Mr. O’Shea said, indicating that scraping tools had been uncovered at the site.

He said the bridge the prehistoric hunters used likely formed when the land rebounded once the weight of the glaciers was removed. During this period of post-glacial adjustment, Mr. O’Shea said the water level of Lake Huron was likely 100 meters lower than it is today, with the entire Saginaw Bay dry land at the time. The basin then filled up approximately 8,000 years ago.

“This gives us a window, and the sites we are studying have been under water since then, so for the most part, they are just how these hunters left them,” he said.

Mr. O’Shea added that the hunting structures the team has located in the Lake Huron depths are often found in the Arctic but are very rare in the Great Lakes region.

“It was probably a lot colder and a lot harsher out there than on mainland Michigan and Ontario, so this was like a refuge for these cold-adapted animals. This was literally the best place for them,” he said. “It would have been good caribou habitat.”

O’Shea said the researchers will spend the winter reviewing the voluminous cache of video of the site, and go back to the lake bottom next year with “a whole new series of issues to investigate.”

Contact Blade outdoors editor Matt Markey at mmarkey@theblade.com or 419-724-6068.