Contested waters: Who's paid for Toledo's water treatment plant?

5/5/2018

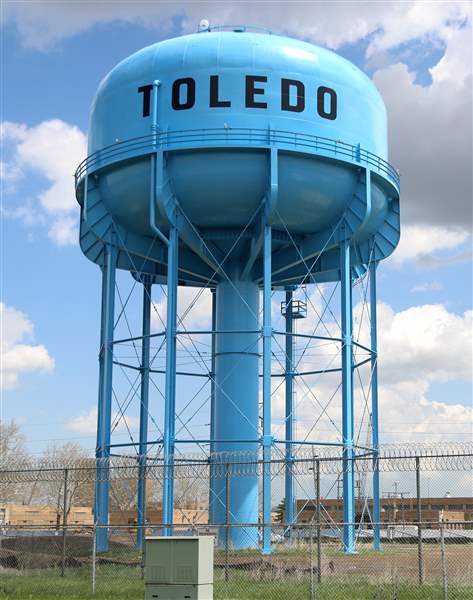

The water tower at the Collins Park Water Treatment Plant in Toledo. Control of the facility going forward is at the center of the debate on a regional water system.

The Blade/Kurt Steiss

Buy This Image

The greatest single public improvement in the history of Toledo.

That’s how the Toledo Citizens’ Waterworks Dedication Committee described the city’s water treatment plant in 1941, the year Toledo stopped getting its water from the Maumee River and switched to a state-of-the-art Lake Erie water supply system.

It was a nearly $10 million project back then — half paid for by Toledo ratepayers and half through federal grants — with a 2017 equivalent cost of about $405 million, city records show. Citizens were so proud of the municipal accomplishment that they published a 60-page book to commemorate the occasion.

The first page is a tribute to water itself: “No human habitation, no great city in all the files of time has been built without it,” the committee wrote. “And in a modern world, no city which fails to make a wise use of it prospers or endures.”

VIDEO: How Toledo’s water plant was paid for

Toledoans have long recognized the value of water — and of the ability to gather, treat, and sell it for consumption.

And now control over Toledo’s Collins Park Water Treatment Plant is at the center of an ongoing debate about if and how northwest Ohio could develop a regional water system.

“I think it’s because you can see it. You can touch it. It’s real,” Toledo Mayor Wade Kapszukiewicz said. “And it is a symbol of something that Toledo has, and opponents of regional water believe it is something that the suburbs are trying to take away from Toledo.”

Officials in both Toledo and its suburbs say now is the closest they’ve been to successfully forming a regional water authority after on-again, off-again discussions since the 1990s.

Soon after taking office in January, Mr. Kapszukiewicz joined leaders of the eight municipalities that buy Toledo’s water in signing a memorandum of understanding pledging to together form the Toledo Area Water Authority.

But not all are on board with jumping headfirst into a regional system, largely because the memorandum of understating proposed TAWA take over the plant.

“Decades ago, some wise Toledoans said, ‘How are we going to get our water purified, cleaned up, and distributed?’” former Toledo Mayor Carty Finkbeiner said at a news conference in March. “Those were Toledoans, nobody from Sylvania, Maumee, Perrysburg, Oregon — those were Toledoans. And ever since then, Toledoans have put in excess of a billion dollars into our water distribution system.”

Suburban leaders and Toledo’s current mayor disagree with that assessment. They believe the cost to upgrade and maintain the plant has been shared by water ratepayers throughout northwest Ohio.

Indeed, a Blade review of available city financial documents found ratepayers have made a substantial investment into the water treatment plant from its construction in 1941 to now. But it’s not quite the $1 billion Mr. Finkbeiner says it is, and it hasn’t all been paid for by Toledoans alone.

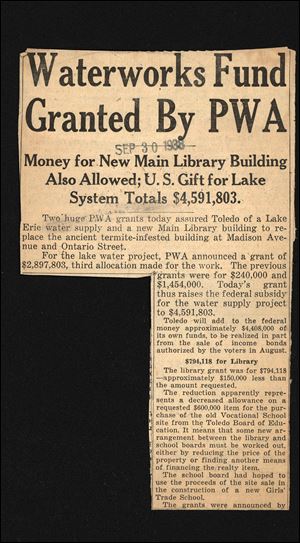

The complex history of the plant’s funding — hundreds of millions of dollars spent over decades by taxpayers throughout northwest Ohio and even beyond — stretches back to FDR’s New Deal policies. In fact 55 percent of the $10 million spent to build the plant in 1941 was covered by a federal Public Works Administration grant.

Major improvements followed in 1953 and 1954, work that cost the city about $4 million.

The 2017 equivalent of the initial building costs plus the cost of those upgrades is roughly $473 million. Excluding the $202 million provided by the federal government, city records show those are the only major improvement costs covered solely by Toledo ratepayers.

The final section of a new waterline that will boost Toledo's raw-water supply by 50 million gallons a day is dropped into place at the Collins Park Water Treatment Plant in July of 1967.

Maumee became Toledo’s first suburban water customer in 1961, followed closely by Sylvania in 1965 and Monroe County in 1969.

From 1964 to 1979 the city constructed a new water main, a new pump station, and an additional reservoir, among other improvements. The work during that time frame originally cost $11.8 million and has a 2017 equivalent cost of $74.3 million, city records show.

Citizens in Toledo and its suburban customers together funded those upgrades by paying their water bills, though the city does not have complete records that break down the revenue generated by Toledo ratepayers compared with suburban ratepayers.

One can guess based on population and usage that Toledoans likely provided the majority of water revenue during that time, said Janet Schroeder, spokesman for Toledo’s public utilities department.

In the 1990s, the only decade for which a water rate revenue breakdown was available, Toledoans made up between 57 percent and 68 percent of the system’s total revenue each year, and by then seven suburbs were buying water from the city.

Lucas County and Whitehouse signed on as customers in 1983, and Perrysburg and Waterville switched to Toledo water in 1987.

Work performed in the late 1980s through roughly 2010 cost the 2017 equivalent of $46.9 million.

From 2014 on — in the wake of the water crisis — the city spent $127 million on improvements, including renovating the low service pump station.

By that point, the city’s water revenues were likely higher from suburban ratepayers than from Toledoans, in part because the suburban populations grew, but many suburban customers also pay higher rates than water users within Toledo city limits.

In 2016 Toledo ratepayers accounted for 47 percent of annual revenue, city records show.

Mayors’ views

In total, water ratepayers both inside and outside of Toledo have invested what today amounts to just over half a billion dollars in building and improving the plant, though the exact percentages of who paid how much can’t be determined with available city records. The addition of $5 million from the Public Works Association — roughly $202 million in today’s money — made it possible for the project get off the ground in the first place.

“I have seen enough to allow me to say that both parties have paid hundreds of millions of dollars jointly toward this plant,” Mr. Kapszukiewicz said. “And that is why I believe going forward the best approach is to create a regional water system to put in practice what essentially has been happening for years anyhow, and that is the shared ownership and operation of our water plant.”

Suburban leaders contend that since their ratepayers now account for more than half the system’s water revenue, they should be afforded an ownership stake in the plant.

If not an ownership stake, then fair water rates; and if not fair water rates, then they say they’ll find their water elsewhere.

“We can’t keep putting our residents’ dollars into a plant and keep improving it and then be treated like second-hand customers,” said Sylvania Mayor Craig Stough, who has been spearheading the push toward a regional water system. “It think it’s a better approach to invest in our own plant if that’s what it takes to get fair treatment.”

Mr. Finkbeiner said he stands by his position that Toledo shouldn’t sell its asset for less than $1 billion, citing a 2012 study and a September, 2017, city council document that values the water system at “approximately $1 billion” to support his claim.

He conceded that the suburban ratepayers helped fund many of the improvements and said they should be recognized “for their contributions in recent years, sure.” But he contends the suburban economic growth never would have been possible if Toledo hadn’t been willing to sell its water to the suburbs in the first place.

“I don’t think anybody would disagree that Toledoans have more invested in that water system than anybody else does,” he said. “We have been there, we have been the leader, and we deserve to be given the respect that a leader who has done that deserves. That did not happen in the negotiations that took place to offer this very poor deal to Toledoans.”

Newspaper clipping from Sept. 30 1938 explaining the PWA grants for a new library and a Lake Erie water supply.

Buy/lease options

The Toledo Area Water Authority would include Toledo, Lucas County, Sylvania, Perrysburg, Maumee, Monroe County, Whitehouse, Fulton County, and the Northwestern Water and Sewer District.

The nonbinding memorandum of understanding signed in January by leaders of each municipality includes options for the new system to either buy Toledo’s water treatment plant out front or take ownership of the facility at the end of a 30-year lease.

It proposes annual lease payments of no more than $12 million and no less than $6 million. It doesn’t propose an out-right purchase price, and a valuation of the Collins Park Water Treatment Plant and Toledo’s other water infrastructure has not been conducted, city officials said.

Mr. Kapszukiewicz has since offered an alternative path to regional water, one that allows Toledo to keep its plant. It isn’t his first choice, as he characterizes the plant as a liability rather than an asset to the city, but he said he recognized other Toledo leaders see value in owning the facility.

“Rightly or wrongly, for better or for worse, there has been a lot of drama surrounding ownership of the plant,” he said. “And if we can accomplish real regional water, and avoid all of the drama, then we should do it.”

He has been talking with Mr. Stough and other suburban leaders about reaching a compromise, but nothing is set in stone.

“We’re all poised and ready to hear the details that they’re working out,” said Nick Komives, the Toledo City Council member who chairs the water quality and sustainability committee. “The majority of council is not in favor of the current proposed MOU.”

Mr. Stough said he would prefer to establish a regional system where the members of TAWA all own the plant, but he is willing to consider an alternative solution if meets three criteria:

• All customers pay an equal price per gallon for wholesale water based on the actual cost of production.

• Water rate contracts must be continuing so that they cannot be unilaterally changed.

• A redundant water source must be developed.

“The devil is in the details,” Mr. Stough said. “Sylvania cannot continue to pay for their capital improvements at their water plant and receive no credit for it.”

Mr. Kapszukiewicz said he believes a deal will be reached by the end of the month.

Contact Sarah Elms at selms@theblade.com, 419-724-6103, or on Twitter @BySarahElms.