Forgotten in history, DeHart Hubbard made it in Paris

4/30/2018

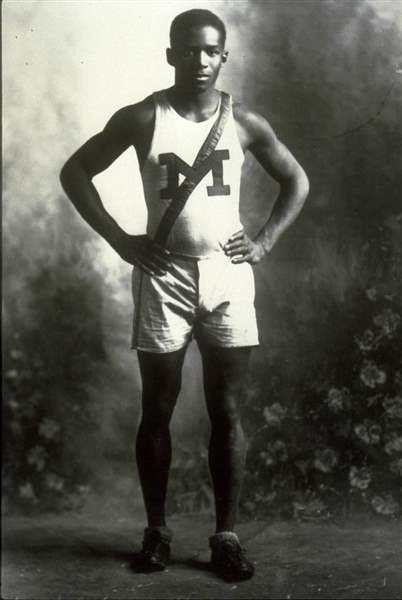

William DeHart Hubbard, a former University of Michigan track athlete, won the 1924 Olympic gold medal in the long jump in Paris.

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

PARIS — Less than 10 miles from the Michigan football team’s palatial hotel in the heart of Paris sits Stade Olympique de Colombes, the host of the 1924 Olympic Games.

The old stadium, now 111 years old, is rickety and considerably smaller than its heyday when it entertained the world’s best athletes. Inside the concrete walls, DeHart Hubbard, one of the University of Michigan’s greatest sportsmen, became the first African-American to win an Olympic gold medal in an individual event, with a leap of 24 feet, 5 inches in the long jump on his sixth and final jump with a bruised heel.

MICHIGAN FOOTBALL IN PARIS: Iconic photos have become part of Michigan lore I Toledo native survived war before starring at UM I Michigan QB discusses NCAA eligibility decision I Patterson case shines light on transfer rights I Michigan bars in Paris serve as home for overseas Wolverines I Wolverines arrive in Paris | Wolverines take 'moving' trip to Normandy

“When I was a student, I came in 1976, and I looked at the school records because I was a long jumper, and that’s when I found out the first notion of who he was,” said James Henry, now the co-head coach of the UM women’s track and field team. “Then I found out he was the first African-American Olympic gold medalist. I was enthralled by him. He was my role model.

“He was at the University of Michigan at a time in which blacks couldn't do very much anywhere. I just felt that if this man can make it, I can make it. Making a name for myself by beating his records meant everything to me. That was my drive as a student-athlete to participate at a high level.”

Despite his accomplishments, Hubbard is an anonymous piece of history, overshadowed by Jesse Owens’ historic exploits a dozen years later in Adolf Hitler's Nazi Germany. But Hubbard’s feats should not go unnoticed.

“As the first African-American to win an individual gold, he’s right up there,” said Teri Hedgpeth, an archivist for the United States Olympic Committee. “It was a major milestone.”

Hubbard’s athletic prowess began at Walnut Hills High School in Cincinnati, where he scored four touchdowns in his first varsity game. As legend has it, four members of the board of education barred Hubbard from playing in the next game — until the rest of the team said, if he doesn’t play, we don’t play.

“My mom was born during that time in the 1920s,” Henry said, “and it made me feel so proud that someone that looked like me did so well under I’m sure extreme pressure during Jim Crow.”

Hubbard was a seven-time Big Ten champion and three-time NCAA champion at Michigan. He set the world record in the long jump — 25 feet, 10 ¾ inches — and equaled the world record in the 100-yard dash — 9.6 seconds — in 1925 and 1926.

Hubbard had the stature of Owens and Carl Lewis before either became heroes and took their place in the pantheon of elite U.S. Olympic athletes.

“What intensifies the spotlight of history is sometimes a matter of timing and events beyond the accomplishment,” said Ken Blackwell, Hubbard’s great-nephew and the former mayor of Cincinnati, Ohio Treasurer, and Ohio Secretary of State.

As Hubbard waited to board the S.S. America to cross the Atlantic, he penned a letter to his parents which included the passage that he wanted to be the first colored Olympic champion, with first colored Olympic champion in capital letters and underlined. Colored was underlined twice.

“I was determined to become the first of my race to be an Olympic champion,” Hubbard told the Cleveland Plain Dealer in 1948, “and I was just as determined to break the world [long] jump record.”

Hubbard qualified for the 100-meter dash and the hurdles but was told they were white-only events, according to Blackwell.

What occurred in Paris was not just a golden performance by Hubbard. He was one of three African-American members of Team USA, and all three returned home with medals — Ed Gordon finished second to Hubbard in the long jump and Earl Johnson took bronze in the 10,000-meter cross country race, run through the streets of Paris in stifling 100-degree heat.

Those names, along with George Poage, the first African-American to win a medal (1904), and John Taylor, the first African-American to win a gold medal (1908), are largely forgotten.

“I don't think it was an era where a lot of press was given to African-American athletes,” Hedgpeth said. “During the 1920s, we saw an emergence of African-American pride. There was the Harlem Renaissance, which fostered music, arts, and literature. There weren't a lot of opportunities for African-Americans, and sports was this area where they could excel. You started to see some awesome events happening, but the mainstream press was not covering it. It was because of the times and what was going on in America.”

At the University of Michigan, Hubbard will be featured prominently in the new track and field facility. Henry, who broke Hubbard’s UM long jump record, wants Hubbard to get his due space, his due time, and his due recognition.

“From my perspective, without him, I don't think I would have strived to do so much because I wouldn’t have had anyone to go after,” Henry said. “I had him. He’s the person I said, I’m going to beat your records.”

Steve Rajewsky, assistant men’s track and field coach, believes it falls on the coaches to keep Hubbard’s memory alive and relevant with today’s youth.

“He’s one of the pioneers of our program,” Rajewsky said. “He accomplished things that many people have never matched since.”

The 1924 Olympics are considered the first modern Games. An estimated 1,000 reporters and 625,000 spectators descended on Paris. Chariots of Fire, which won the 1981 Academy Award for Best Picture, is based on the 1924 Games and the story of Eric Liddell and Harold Abrahams. Liddell was a devout Scottish Christian who devoted his life to God and Abrahams, an English Jew, battled anti-Semitism.

Hubbard is depicted in the film. All three won gold medals — Hubbard the long jump, Liddell the 400 meters, and Abrahams the 100 meters. Liddell famously skipped the 100 because his heat fell on the day of the Sabbath, a decision that drew admiration from Hubbard.

“He was really truthful when he said he [was satisfied because he] won a gold medal, he set a world record, and he got to witness Eric’s fidelity to his faith,” Blackwell said. “He thought that was as important as any gold medal.”

When Hubbard returned home from the Olympics, he was a gold medalist and a UM graduate who finished in the top 10 percent of his class. Yet all he could find in the way of employment was a position as supervisor in the Department of Colored Work for the Cincinnati Public Recreation Commission. Hubbard also founded the Cincinnati Tigers, a Negro league baseball team.

In 1942, he moved to Cleveland and became a race relations adviser for the Federal Housing Authority. Ironically, Hubbard, Owens, and Harrison Dillard, one of the U.S.’s most accomplished black track athletes, all lived in Cleveland. The friends would gather and swap old stories.

“Very few people are timeless,” Dillard wrote in the Cleveland Press after Hubbard’s death. “Jesse was timeless. I’ll talk to different kids groups and they wonder, ‘Who on earth is Harrison Dillard?’ Even more would have to wonder, ‘Who is DeHart Hubbard?’ DeHart was timeless also and very Intelligent. But there was something more about Hubbard. It was his demeanor. He was not a boisterous person. There was a sense of the gentleman about him.”

President Lyndon Johnson considered Hubbard as the first Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, a position Hubbard declined. Hubbard also served as president of the National Bowling Association in the 1950s.

“He was more than just an Olympic gold medalist,” Rajewsky said. “If you look at what he accomplished in his life, that’s just as impressive.”

Contact Kyle Rowland at krowland@theblade.com, 419-724-6110 or on Twitter @KyleRowland.